A united Africa may give China its moment to shine

AfCFTA will likely complicate existing agreements with Africa’s main partners, including the United States and China.

Niamey, Niger – The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) promises to raise the standard of living for more than a billion people by making it easier for Africans to trade with Africans. But its impact will not be restricted to the continent: The historic deal will likely impact Africa’s existing agreements with China, the United States, and Europe.

“To make the deal work, we’ll need Africa’s main partners to support a multilateral trading system,” the World Trade Organization’s deputy director-general, Yonov Frederick Agah, warned during the AfCFTA’s launch ceremony in Niger, on July 7.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS imposes new sanctions on Iran after attack on Israel

A flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

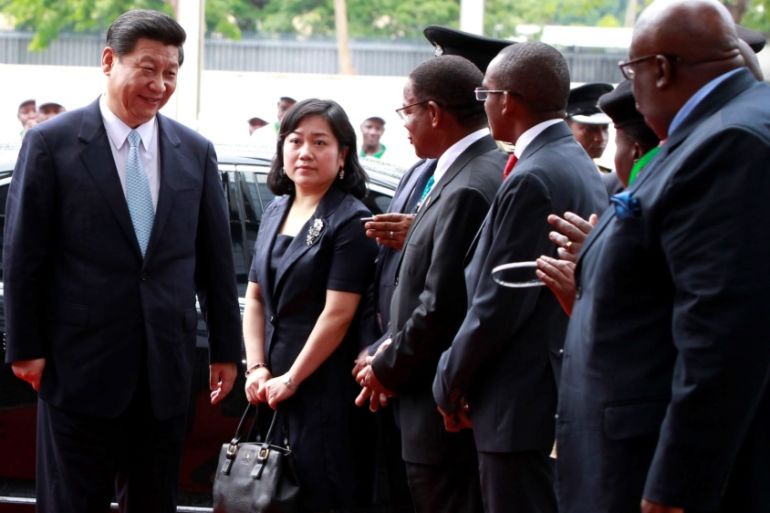

While the US and China look for common ground, the middle kingdom’s economic footprint in Africa continues to grow and might benefit from both US unilateralism and the AfCFTA.

Beijing’s praise

“The launch of the AfCFTA breaks new grounds for China-Africa cooperation,” said Geng Shuang, a spokesperson for the Chinese minister of foreign affairs. Beijing, he said, will continue investing in “infrastructure connectivity, trade facilities and industrial promotion” under the country’s Belt and Road Initiative.

In 2018, US-Africa trade shrank to $61bn, barely 45 percent of its 2008 value. During the same period, the value of trade between China and Africa exceeded $200bn, and projections suggest it is still growing.

AfCFTA critics argue that inexpensive Chinese products will “invade” the African market, damaging local manufacturers’ business, but Tanzanian businessman Ali Mufuruki disagrees. “This is no news: our shops are already full of Asian household articles, electronics and cars,” he told Al Jazeera. “We’re importing everything since decades [ago], while all our resources are shipped out of the continent and our manufacturing sector is still too weak.”

Instead, he said, “the AfCFTA is an opportunity to reverse this trend”. With a rapidly growing internal market of 1.2 billion consumers, “African companies will be pushed to get bigger and go international”.

AfCFTA’s entry into force

Only 28 countries have ratified the AfCFTA agreement, and 26 more (as Eritrea is not to count in yet) are expected to follow soon. Eritrea has still not signed on. On July 1, 2020, most AfCFTA-ratifying countries will start removing customs tariffs on 90 percent of imported goods that were made in Africa, with the aim of removing them completely before 2035.

“At first, countries with fragile economies might lose revenues from customs exemptions and competition of cheaper goods from other continental partners”, the African Union’s Trade and Industry Commissioner, Albert Muchange, said. A half dozen AfCFTA-ratifying countries will then start removing tariffs on only 75 percent of African-made imports to soften the impact of liberalisation on their internal market.

“The game has just started,” said Mukhisa Kituyi, the secretary-general of the United Nations Conference for Trade and Development. The conference played a key role in shaping AfCFTA’s technical details. “Investing in transport, logistics, and infrastructure will be a huge challenge since it’s now cheaper for an Ethiopian good to reach China than Nigeria,” Kituyi told Al Jazeera.

Ghana: back door for foreign goods?

Ghana will be home to AfCFTA’s headquarters, and while the country is one of the continent’s rising stars, its success could prove to be a vulnerability for the bloc. With $3.3bn of foreign investments in 2018, Ghana is a top destination for multinational firms. Nissan, Suzuki, and Volkswagen will open plants in the country in 2020, transforming the region into a hub for the African car industry.

And yet, it is that very openness that scares other African countries. “Let’s take a Chinese company that will open a shoe factory in Ethiopia, using cheap Chinese leather,” said Kituyi. “Will they exploit tariff exemptions under the AfCFTA to sell their shoes in other African countries?”

The answer, he explained, is in the definition of “rules of origin”, which Kituyi described as “a process that will give a passport to each product”.

“If shoes are ruled as ‘made in Africa’, because their local added value is more than, let’s say, 40 percent, then they will circulate freely,” said Kituyi. “Otherwise, they’ll be considered as a Chinese product.”

Ongoing negotiations on rules of origin will make sure “to exclude dumping of cheap goods by third countries”, noted Kituyi.

“The agreement will open up opportunities for Ghanaian manufacturers,” said Ghana’s Trade and Industry Minister, Alan Kyerematen. He also noted it will “stimulate new home-grown businesses and further attract foreign direct investment”.

Complicating relationships

While AfCFTA could complicate already-existing trade agreements – between African nations, the US, the European Union and China – Ghana’s trade and industry minister is not worried. This “won’t pose any problem, as [the trade agreements] are not mutually exclusive and will foster competitiveness,” Kyeremate told Al Jazeera. “Ghana is a gateway for investors, that from here will be able to reach all the AfCFTA”.

Kituyi worries that a recent move by the administration of US President Donald Trump to restart “bilateral agreements with African countries” works against African’s effort to build a common market. If the US would “change their position and embrace negotiating with the continent as a whole, we’ll have grounds to celebrate”, the UN official said.

Rwanda‘s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Richard Sezibera, said he would also welcome “negotiated agreements with the US, such as those we’re conducting with Europe”.

His country’s trade policy was in the spotlight in 2016, when Rwandan President Paul Kagame raised taxes on Western-imported second-hand clothes, prompting the US to raise its tariffs on Rwandan imports.

“If we want continental free trade to benefit us, we need made-in-Africa products, and the textile sector is a perfect example of this”, Sezibera told Al Jazeera. In Rwanda, US retaliatory measures finally benefited China’s clothing companies such as C&H Garments, which opened huge factories in Kigali. Their “made in Africa” products might enter the AfCFTA in the near future.

Rwanda, Sezibera stressed, “is the second-best place to do business in Africa and the 29th in the world according to the World Bank”.

“We’re growing our airline, attracting ICT companies and working to create cheap energy,” he said. “So for us, [last month’s] Niamey summit has been history in the making”.

Security

Even as intra-African trade becomes easier, security remains a challenge on the continent. “Our instability also affects our exchanges and economic development,” the Central African Republic’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sylvie Baipo-Temon, told Al Jazeera, pointing to the recent African Union-brokered peace agreement that promises to end a deadly seven years of civil conflict.

But the free trade zone, she said, “motivates us to strengthen the peace process, so that we might regain control over all our territory and trigger our full economic potential, especially in agriculture, which employs 75 percent of our labour force and needs to become more productive”.