A day in the life of a London food bank

The wife of a policeman, the daughter of a grocer, an unemployed builder and an asylum seeker: How a growing number of people from different walks of life are turning to food banks in the UK.

Outside a one-storey, blue-and-yellow building in Brent, northwest London, people are beginning to gather. It is 10:30am on a Tuesday in mid-December. An elderly woman shelters beneath the entrance as it starts to spit with rain. At 11am, the Sufra Food Bank on St Raphael’s Estate will begin distributing its first emergency food parcels of the day.

Situated between Wembley and the North Circular – a 40-kilometre (25-mile) ring road around Central London – St Raphael’s Estate is Brent’s most disadvantaged neighbourhood. Prevalent since the post-war years in Britain, housing estates like St Raphael’s initially flourished, providing homes to rent at low cost, yet many have since become run down and neglected.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUK’s fresh food supply at risk until Dover backlog cleared

The UK’s newest front-line workers: Afghan fruit sellers

Pandemic to push 47 million more women, girls into poverty: UN

Recent statistics show that one in three Brent households live in poverty while, nationally, one in five live below the poverty line. Now, increasingly more people are being pushed under the threshold, finding themselves unable to afford basic essentials.

In recent years, food bank usage in the UK has risen sharply following 10 years of government austerity measures, welfare reforms and a widening gulf between earnings and living costs. With the economic downturn brought on by the pandemic, which has further exacerbated existing inequalities, food banks across the UK are struggling to meet demand.

“COVID didn’t create this problem, it just helped people to actually see it,” says Fahim Dahya, Sufra’s logistics and facilities manager, who helped set up the food bank with founder Mohammed Sadiq Mamdani in April 2013, after working at a local youth camp and witnessing the hardship families were facing in the area.

Starting out working from a shared office in South Kilburn, they soon managed to raise enough money to relocate to the current building in Brent. When they first arrived, Fahim remembers the building was in total disrepair: Broken windows, no boiler, no heating, leaking ceiling, mouldy carpets. And the most vital part – the kitchen – was the size of a cupboard. But they were introduced by Brent council to John Sisk & Son, the company which built the Wembley Stadium flats, which offered to renovate the place for free. Later, they applied for grants which enabled them to employ a team of full-time, paid staff.

Now, approximately half of Sufra’s income comes from individual donors and businesses via community fundraising. The other half comes from charities, trusts and foundations which it applies to for support grants.

While demand for the food bank has grown steadily over the years, the pandemic has brought unprecedented challenges. With many businesses forced to close, employees in the UK with less or no work are being put on a furlough scheme, which ensures they still get 80 percent of their regular wage.

“We were expecting it to explode this week because the furlough scheme was going to end, then that got extended so the explosion hasn’t happened yet, but it’s going to happen very soon,” says Fahim.

During the initial lockdown in March, the food bank experienced a 200 percent jump in demand compared with 2019 because of widespread job losses. “You’re not ready for that, and with the shops limiting stock, it was really, really difficult,” Fahim says. “We’ve got two phones and both lines would be constantly ringing.”

Not only was the food bank understaffed for the extra demand, but it was also forced to limit the number of volunteers it could have in the building because of social distancing, so the charity had to adapt quickly.

This meant closing the food bank for four months and switching to 100 percent deliveries so that people could still receive emergency food parcels during the lockdown. They also had to implement a new phone system to support remote working – a difficult transition for a close-knit team who rely on direct, face-to-face communication and a job in which being on the ground is often essential for the nature of the work.

As Fahim says: “You don’t know what’s going on unless you’re on the ground and you feel it, see it.”

‘Much more than just a food bank’

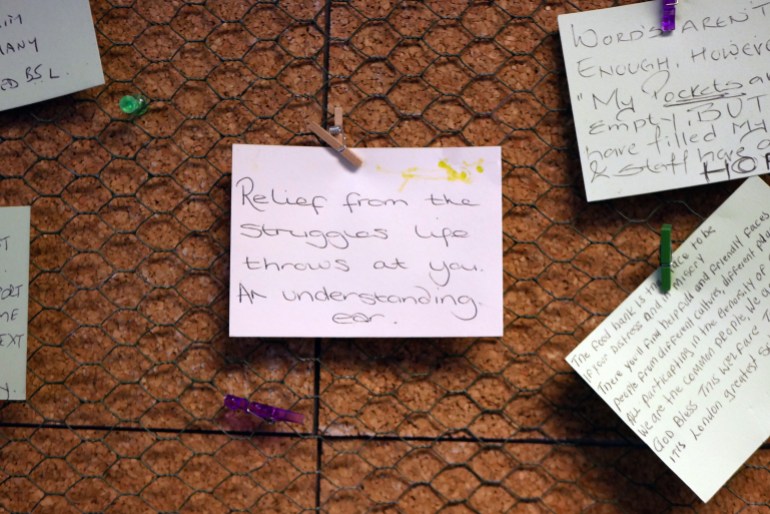

At the start of the day, Nina Parmar, a volunteer coordinator, gives me a tour of the site. “I think that Sufra is so much more than a food bank,” she says. “Community is at the heart of the different projects run by Sufra – we know that food aid is not the solution to food poverty and we are working hard to support our guests in so many other ways towards no longer needing to access the food bank.”

Before the pandemic got under way, food bank guests would be invited inside and offered a cup of tea while waiting for their parcel to be packed.

On Friday nights, Sufra’s community kitchen would draw up to 90 people and serve a freshly cooked three-course vegetarian hot meal to anyone who turned up. For many residents, it was a much-loved social event encapsulating the meaning of the Arabic term, Sufra (or “Come to the table”). But, for now, the community kitchen is closed, with meals delivered instead, while others collect their food parcels at the door. “The process has become a lot more sterile,” says Nina. “We’re just trying to be as risk-free as possible.”

Today, the main space inside the food bank is empty barring a couple of volunteers sorting through boxes of donated vegetables from supermarket surplus.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reveal that Brent had the highest overall COVID-19 death rate out of all regions in England from March to June, a stark reflection of how the most deprived areas – especially those with a high concentration of Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities – have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

Across the road, in a separate building with a storage facility, two volunteers pack food parcels according to family size. Designed to last a week, each parcel is filled with non-perishable food items, a bag of fruit and vegetables and toiletries.

“On an average foodbank session at the moment we have around 35 to 40 parcels collected,” Nina says. “In a week, across delivery and collection, we’re currently providing almost 300 parcels which are supporting just under 800 recipients.”

Once prepared, parcels are shifted over to the main building. Limited space means staff have to coordinate across multiple locations which, Nina explains, is not ideal. Scanning the shelves, she addresses a more pressing concern: They are going through food at an alarming rate. In the first six months of the pandemic, Sufra delivered 19,111 emergency food parcels and 34,324 fresh meals. While it still receives food donations and funding, Nina says the food bank cannot continue at the rate it is going.

Back in the office, in the main building, Fahim explains Sufra’s holistic approach to food aid. “We started with the intention of a food bank and a kitchen. Now they may be our core services, but they’re only really there to get people’s feet through the door so we can actually help them, because that one food parcel in the reality of your life is nothing. It keeps you fit for a week, but it doesn’t solve any problem apart from that problem being there next week.”

Usually, people are referred to Sufra by one of the 100 referral agencies it is registered with in the local area, including Brent Council and Citizens Advice. But if someone turns up at the door without a referral, they are directed to call Brent Hubs – another referral agency – and asked to fill out an online form.

While they do not want to be cold and strict, Fahim believes an open-door policy would be impossible to manage. “That formality needs to be there because it stops people from abusing the system. Also, it’s there to stop us creating a dependency. This is emergency food aid and it needs to be treated in that way, otherwise, it’s not manageable or feasible.”

A voucher limit also ensures that once a person hits six food parcels, their case is assessed by Sufra’s advice workers. “We then need to look at it because we’re now going from short-term emergency aid to long-term support,” says Fahim. “It’s also a way we can engage people, find out what their problem is, why they’re in that situation so that we can either signpost them or refer them to our advice workers to try and help them out.”

Sufra currently has two full-time advice workers – Ros and Zena – who provide practical support for food bank guests with more complex issues, such as social benefits, housing, employment and immigration status.

Born in Trinidad, Ros Baptiste moved to the UK when she was 11 years old. She spent her teens in Yorkshire and then moved to London about 10 years later. As a resident of the estate for 38 years, Ros has witnessed the changes to the area with the UK’s largest regeneration project under way in neighbouring Wembley with plans to build 11,500 homes by 2026 – many of them luxury apartments. She has also personally experienced the neighbourhood’s unique isolation marooned as it is between the stadium and a dual carriageway.

“You do get isolated. We are cut off,” she says. “We’ve learned over the years to plan around [Wembley stadium] event days. If there are road works going on anywhere, we have to organise around that as well. It all impacts on the North Circular, so the estate gets used as a second version of the North Circular, basically.”

In fact, part of the aim behind the community kitchen at Sufra was to combat social isolation. “[Social isolation] is one of the big triggers of mental health,” explains Fahim, “which triggers homelessness … It’s all part of the cycle. [The community kitchen] is a way of getting them out, getting them involved in something.”

When Sufra first set up on the estate, Ros volunteered to work in the community kitchen every Friday, but after being made redundant in 2017, she ended up spending more time at the food bank than at home. Now, she works full-time at Sufra as a welfare advice worker, a role that encompasses everything from one-to-one casework, to running workshops on subjects like tenancies, energy efficiency, how to read and understand gas metres and talk to energy suppliers – a system Ros is adept at navigating because of her previous job working for an energy charity.

Due to the pandemic, Ros says she is seeing more cases than usual because of job losses and benefit delays. She estimates she currently has about 30 open cases at various stages.

“[I’m seeing people with families] who were furloughed during the first wave of the pandemic, working part-time, claiming Universal Credit,” she says. Introduced in 2013 by the UK’s Conservative government, Universal Credit aimed to simplify welfare by replacing six existing benefits (including jobseeker’s allowance and child tax credits). The government heralded it as a way to encourage people back into work (as it is paid to working people as well as those seeking employment) but it has since been criticised because of backlogs, delays in paying it and the problems caused by recalculating it when people’s incomes change.

“So, once furlough stopped, I’ve got families whose income has now dropped to less than half of what they had,” she says.

Ros adds that many people are having to decide between buying food or heating their home, an impossible choice in the UK in winter when temperatures drop to less than three degrees Celsius (37 degrees Fahrenheit). “Some of the people that come to me, they come because there’s nothing left. Luckily, the majority of them are usually getting Housing Benefit (which helps those on low incomes with housing costs). However, that doesn’t cover food or bills.”

Working full time, but no money for food

Anthoinette, a mother of two, is visiting the food bank for the first time. She has taken a bus to get here and arrives with her 10-month-old daughter, who blinks wearily at me through the pram’s plastic window.

Anthoinette suffered from complications during delivery and had to have a caesarean. After the birth, she was advised to stay home because of her health and the risk of contracting COVID-19. Her daughter, meanwhile, had to remain in hospital as it was discovered she had three holes in her heart and needed an operation. She also had two eye surgeries because of problems with her corneas.

It was a stressful time for Anthoinette, especially seeing her baby on a ventilator. She also quickly realised she needed extra support. Unable to work, she is now a full-time mother. Although her husband works full-time with the Metropolitan Police, his salary does not stretch far with the high living costs in London. But, “he’s doing his best,” she says.

“COVID was another problem,” she adds. “He has to go to work and I am home and there is no food. I can’t go out to the shop. I can’t cook. I can’t sleep. It was too much.”

Anthoinette contacted an organisation called Home-Start, which helps families struggling with issues such as postnatal depression, isolation and physical health problems. Home-Start referred her directly to the food bank. “They helped a lot because the pregnancy was tough and after [my baby] was sick, I couldn’t eat. I’d come back to my house depressed, so they were the ones helping me deal with a lot of things,” she says.

“There’s millions of people in this country and lots of families need help. It’s hard because the pandemic has slowed the economy. A lot of things have gone wrong. Many parents lost their jobs because of COVID and it’s hard for them to feed their kids. I’ve never had to use a food bank before. This is my first time.”

Anthoinette and her husband are not the only family with a wage coming in who is struggling. According to the Trussell Trust, a network of food banks in the UK, one in seven people coming to food banks are in employment, or live with someone who is.

Lynne Kennedy, professor of Public Health Nutrition and head of the Department of Clinical Sciences and Nutrition at the University of Chester, says: “Based on our research locally, exploring the lived experiences of food poverty and access to food during COVID, we have found that, unlike previously, a higher number of people who are struggling to make ends meet are in full or part-time employment, and/or furlough; families talk about the genuine struggle, living from one bill to the next, any unexpected demands or bills can cause a downward spiral, with food budgets the first to be cut because they are the most flexible household item.

“What is particularly interesting is that because this is the first time for some families to fall into poverty or financial hardship, they lack the strategies used by those families who might be used to living ‘on the breadline’, so to speak, who are able to draw upon strategies or support networks in times of emergency.”

The asylum seeker

Wais Sultani’s face lights up when he recalls his previous job in Afghanistan. He held a managerial role greeting VIP guests at Kabul Airport but was forced to leave after the war escalated in Afghanistan. Wais, 29, says the Taliban tried to recruit him, but as he did not agree with them they began sending him death threats. That was the moment he decided to flee the country.

Wais came to the UK in 2015. But after submitting his asylum claim, it was denied although he says he does not know why. He is now making a new asylum claim but he does not have permission to work. He initially slept at friends’ houses and sometimes worked a cash-in-hand job at night cleaning at a shop in South London just to be able to buy some food.

After getting married last February, however, Wais’s expenses increased. While he waits for a decision from the Home Office on his new asylum claim, Wais has been living with his pregnant wife and their eight-month-old baby in a basic hotel room provided by the council.

They have now been there for four months. Wais receives 100 pounds ($136) a month from the council, which he says is not enough to cover basic necessities. After approaching social services for support, he was directed to Sufra. Today, it is his sixth visit in the past two months.

“Before the pandemic, things were good; at least my friends helped me,” he says. “But since the pandemic started, no one even listens to me or wants to help me. I hope one day I’ll get the work permit, start working and have a happy life with my wife and sons.”

‘If I can help someone, it’s good for me’

Back inside, 68-year-old volunteer Abdalkarim Sama is taking a quick lunch break.

“I like helping people. If I can help someone, it’s good for me,” he says. Born in Uganda, Abdalkarim moved to the UK in 1971 and worked as a metal engineer in Wembley until his last firm, which he managed, shut down seven years ago. One day at the supermarket, he saw volunteers collecting for Sufra so he asked if he could help out. He has been volunteering with them ever since.

Reflecting on his seven years at Sufra, Abdalkarim recalls one particular encounter that has stayed with him: “There was one guy who asked for food. He hadn’t eaten in a long time. Once he started eating, he said, ‘I feel like a king’. It made me feel like I’m doing something to help, and I always wanted to help people. Back in Uganda, my father used to do the same thing, helping people who had problems getting food.”

Throughout the afternoon, more people come through the food bank. Someone collects food for a family of six. A Polish man who lost his job as a builder after he broke his leg in an accident and now lives in a hostel arrives. A mother and her 19-year-old daughter, who have travelled from the nearby suburb of Neasden after being referred to the food bank by a doctor since the father’s earnings from his job as a grocer do not cover expenses after rent and bills are paid each month. While the food bank has been a lifeline for them – especially during the pandemic – the daughter is determined to find work. She says she has been applying for a year and cannot get a job. “It’s really hard,” she says. “I wish somebody would give me a job. I don’t mind doing cleaning, at least I get paid.”

By 2:45pm, 15 minutes before the food bank closes for the day, there have been 25 food parcel collections – a quieter day than usual. But Sufra’s work is not finished. In addition to a food parcel delivery service for those unable to collect in person, Sufra runs a daily hot meal delivery service which remains ongoing since May, designed for people with physical or mental disabilities who are unable to cook, as well as homeless people in temporary accommodation which lack cooking facilities.

Muhammad Yawar Ali, 38, is one of Sufra’s paid delivery drivers. He never intended to enter the charity sector, but was made redundant from his job last year and saw that Sufra was recruiting. Before this, he was working for a company but says he cannot imagine returning to an office job now.

Ali shows me a list of the addresses he will be delivering to this evening and uses an app on his phone to map the best route.

“We all have our struggles,” he says. “But the thing is when you get stuck in your own bubble you think it is what it is, but it isn’t. You see other people and realise that your struggles aren’t that much; people are actually in more difficult positions than you are. It puts things in perspective.”