Palestinian Authority struggles to pay public employees

High inflation, dwindling donor aid and Israel’s withholding of vital tax funds are squeezing the PA’s already decimated budget.

Ramallah, occupied West Bank – After years of economic stagnation, authorities in the occupied West Bank say they are struggling to pay salaries for public employees, as soaring inflation, dwindling donor aid and Israel’s withholding of vital tax revenues strangle the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) already crippled budget.

“The conditions we are living in are difficult, we are in financial deficit,” Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh admitted this week, telling reporters the PA has not received aid to pay salaries, estimated at a monthly cost of 920 million Israeli shekels ($292m).

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUN agency for Palestinian refugees faces funding crisis

EU-funded Palestinian school faces Israeli demolition

‘Flagrant blackmailing’: Palestinians denounce US-UNRWA deal

The financial crisis – described by officials and analysts as “the worst” since the PA’s establishment in 1993 – has left workers anxious.

“At first, we heard that we would not get paid at all. Then we were told that we may get a permanent 25 percent deduction on our salaries. After that, they said that the 25 percent deduction would only be for a few months,” a PA public employee told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

“Until now, nobody knows whether we will get paid or not, or if we’ll get our salaries in full or only 75 percent of it.”

Like economies the world over, Palestine is currently wrestling with soaring inflation stemming from supply chain snarls and shortages of raw materials as nations cast off coronavirus restrictions.

The PA’s fiscal revenues declined to their lowest levels in 20 years shortly after the start of the pandemic, which only exacerbated longstanding financial challenges.

While support from foreign donors has withered over the years, the biggest blow was dealt in 2017, when former United States President Donald Trump cut off nearly all US aid to Palestinians. Though Trump’s successor, Joe Biden, has reopened some of the funding taps, US laws now prohibit direct aid to the PA.

In November, Shtayyeh’s adviser for planning and aid coordination, Estephan Salameh, told local media the crisis could last six months before expected European Union aid worth 600 million euros ($680m) arrives in March.

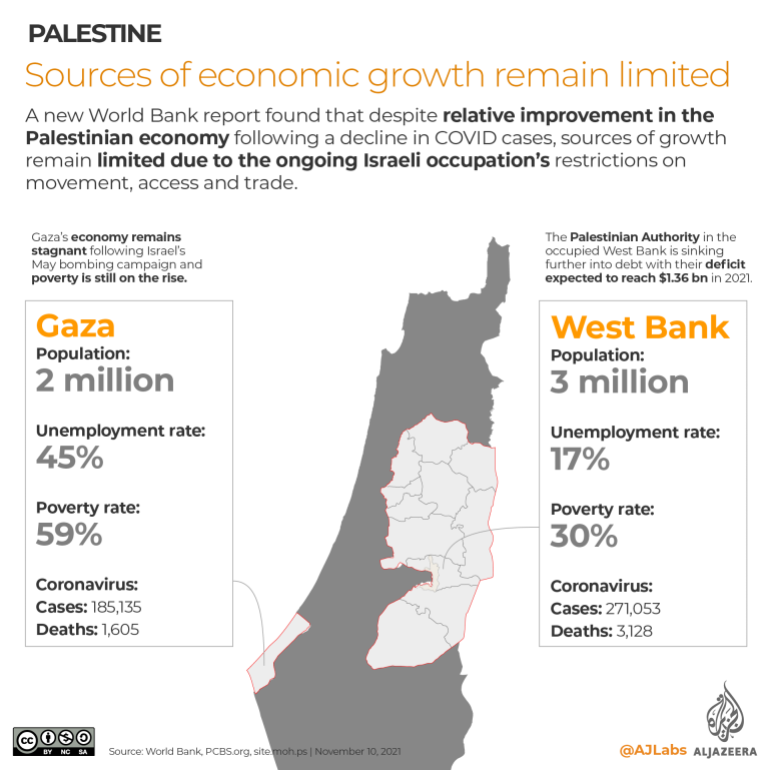

A November 17 World Bank report (PDF) said the PA’s deficit is expected to reach $1.69bn by the end of the year, while donor aid is “projected to amount to $184m – 38 percent of what was received in 2020”.

“Efforts by all parties are critical to avoid a crisis as without additional financing, the PA may encounter difficulties in meeting its recurrent commitments towards the end of the year,” the report warned.

In September, Israel said it loaned the PA 500 million shekels ($155m) to be paid back by June 2022 in order to “prevent its collapse”, according to Israeli media.

Old solutions not an option

Jaafar Sadaqa, a Ramallah-based economic analyst, said there was grave uncertainty over whether a long-term solution would be found.

In previous financial crises, Sadaqa said, donor countries “would rush to pay off the required amounts and would often even increase their financial assistance to the PA”.

Things are different now, however.

In October, before embarking on a European tour with the aim of mobilising political and financial support, Shtayyeh told a special session of the Palestinian Authority that foreign aid had dropped by 90 percent this year. The decrease in international aid has left the PA with a financing gap of $704m in the first eight months of 2021, according to the World Bank, with funding for its core budget at 10 percent of what it was last year.

And this time, observers say the PA may not be able to borrow its way out of the squeeze, either.

“In the past, the PA would also resort to borrowing from banks and returning it when the crisis was over. However, banks are currently unwilling to lend to the PA since it has no collateral,” said Sadaqa.

The PA’s debt to local banks amounted to $2.5bn as of August 2021. Domestic bank borrowing, meanwhile already exceeds the limit set by the Palestine Monetary Authority (PMA), “eliminating this financing option going forward”, according to the World Bank.

At this week’s news conference, Shtayyeh also warned that the PA “may not be able to borrow from banks” this month. “We hope in the coming days to fulfil our needs” he added.

Israel adds to PA woes

Compounding the PA’s woes are sharp declines in tax revenue – another pillar of its budget – due to Israel’s routine refusal to hand over a portion of the so-called “clearance revenues”.

The funds – taxes collected by Israel on behalf of the PA, including customs duties – account for more than 60 percent of the PA’s annual revenues.

As part of the 1994 economic deal between Israel and the PA known as the Paris Protocol, those funds are meant to be transferred to the PA on a monthly basis. But Israel has frequently turned these funds into a political bargaining chip, by refusing to hand over the money in whole or in part until the PA bends to its will.

In January and June 2021, Israel deducted 50 million shekels ($16m) per month from the clearance funds, citing the PA’s cash stipends for families of Palestinian prisoners and those who were killed by Israel. In July, Israel increased the monthly deductions to 100 million shekels ($32m).

“These monthly deductions represent a significant strain on the Palestinian fiscal situation,” the World Bank says.

Beyond the financial weaponising of tax revenues, the PA also has to deal with myriad fiscal leakages and structural problems caused by Israel’s occupation.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) said in a report (PDF)last week that since the Second Palestinian Intifada or uprising in 2000, the occupation has cost the Palestinian economy in the West Bank some $57.7bn in closures, restrictions and military operations.

“Israel imposed a complex system of mobility restrictions, which has effectively turned the West Bank into isolated islands. Those measures paralysed economic activity, inflicted serious dislocations, and significant income losses and thus aggravated pre-existing and deep-seated structural weaknesses and vulnerabilities,” the report said.

“They have entailed long-lasting effects, including volatile economic growth, persistently high unemployment and poverty rates and chronic internal and external deficits.”

Israel’s occupation effectively isolates Palestinians from international markets, making them heavily dependent on Israel for trade. Last year, Israel accounted for 80 percent of Palestinian exports and 58 percent of imports, according to UN figures.

In US dollar terms, Palestinian imports from Israel last year were worth $2.77bn, and exports less than $1bn, according to the US Department of Commerce.

‘No longer enough’

As the PA tries to navigate its way out of the fiscal squeeze, lower-income public sector workers are struggling to keep food on the table.

A PA civil servant, who also spoke to Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity, said food price spikes were making it increasingly challenging for her to feed her family of eight on her fixed income – which has not been adjusted for inflation.

The sole breadwinner for her household, the public servant said she used to be able to afford to buy five chickens a week to sustain her family. Now, she can only afford three. And prices of other staples, such as sugar, rice and flour, are also going up.

“After the sharp increase in prices, there is now an extra expenditure which was neither foreseen nor accounted for, which has added an extra burden on our family,” she said.

Ibrahim al-Qady, the head of the Consumer Protection Agency affiliated with the PA’s Ministry of Economy, told Al Jazeera there has been fearmongering surrounding the issue of price hikes.

“Palestine has been affected by this price increase just like any other country worldwide,” he said, adding that his agency has intensified its supervision of markets to ensure there is no price gouging.

But for those wrestling the burden of stagnant income and rising prices, the future looks bleak.

“We are afraid that prices will continue to rise,” Mujahed al-Assa, who owns a clothes store in Bethlehem, told Al Jazeera.

The 32-year-old said he has cut back on buying sugar but was worried inflation would only get worse, making life more difficult for his small family as his income was “no longer enough to cover the expenses and needs of the house for a whole month”.