Love them or hate them, the Kardashians changed business forever

In the final season of their show, the Kardashians remain modern-day marketing geniuses who changed how people watch, click and buy – and whose family milestones reflected broader cultural shifts

To say that the 20th and final season of Keeping Up With The Kardashians, which airs on Thursday, signals the end of an era is not only a cliche, it is plain inaccurate. Keeping Up With The Kardashians created an entire world anchored in social media – and in many ways, this era is only just taking off.

The show – based in Los Angeles in the United States – premiered in 2007, just a few months after the debut of the iPhone. Low-rent reality shows were already de rigueur on cable channels, but even the most successful ones – The Osbournes, The Simple Life, Laguna Beach, The Hills – barely caused a ripple beyond a small pop culture bubble.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsDisney to reopen California parks a year after COVID closed them

Beyonce won her 28th Grammy for Black Parade

Alberta politicians slam ‘vicious’ Netflix cartoon for kids

Some reality stars got commercial licensing deals; some got magazine covers. And while network reality shows could become megahits across demographics – The Apprentice starring Donald Trump regularly scored more than 10 million viewers per episode – reality shows on cable television were relatively inexpensive to produce and easy to market test in real time. No audience? No problem: cancel it.

That is why many reality shows developed for cable television became blink-and-you-miss-it casualties (example: House of Carters, about former Backstreet Boys singer Nick Carter and his family, which ran for a total of eight episodes on E!).

So what made the Kardashians stand out while other families fizzled out?

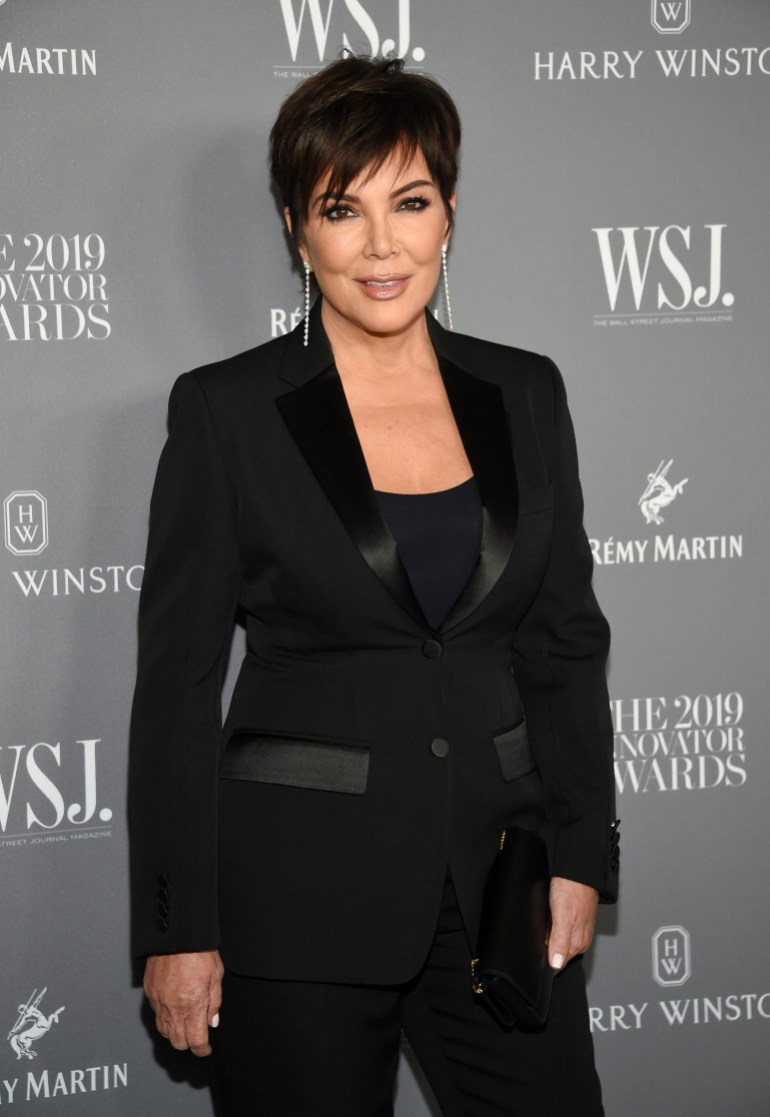

Some say the answer lies in the marketing genius of “momager” Kris Jenner, whose net worth stands at an estimated $190m, according to Forbes, and who takes a 10 percent cut of her children’s modelling, licensing and beauty deals – as well as $100,000 per episode for their show.

“There’s a lot of people that have great ideas and dreams and whatnot, but unless you’re willing to work really, really hard, and work for what you want, it’s never going to happen,” Jenner told The New York Times newspaper in 2015. “And that’s what’s so great about the girls. It’s all about their work ethic.”

And that, experts say, is where the Kardashians stood out from the rest of their reality show counterparts.

The Kardashians knew what they wanted – fame – and they developed their own road map to get it.

‘Social-first approach’

While other reality show stars may have lived their “real” life when cameras turned off, the Kardashians realised early on that the wattage of a reality star is only as bright as its visibility.

While editors and corporations were the gatekeepers for prior reality stars, the Kardashians jumped on emerging social trends to become omnipresent.

“Prior to the Kardashians, celebrities would see social media as something they had to tick off a box to get done. They would hire a social team to do it,” Eric Dahan, the CEO of Open Influence, an influencer marketing agency, told Al Jazeera. “The Kardashians saw the value in speaking organically to their fans.”

And unlike celebrities who only showed picture-perfect red carpet appearances, the Kardashians kept it real. Take, for example, a 2009 tweet in which Kim Kardashian announces that “i have a really odd talent. I can smell when someone has cavaties” (sic).

That tweet generated nearly 20,000 retweets, 27,000 likes and is still being brought up as news more than 10 years later, as exemplified by a December 2020 People magazine story.

“The Kardashians had a social-first approach, where they became their product,” Dahan explained.

Living on social media in the early age of smartphones gave Kim Kardashian much more saturation than she would have had if she had only lived in paparazzi photos or reruns while also allowing her to tightly control her own image. And that shift – image becoming the product – ushered in our social-first era, said Dahan.

A ‘confessional’ culture

What started as a frothy show about a rich and famous family took on a much deeper meaning during the 2010s.

Divorce, addiction, and gender identity were issues the Kardashians tackled head-on – with the cameras rolling. They had transitioned from reality TV stars to driving news stories: Caitlyn Jenner’s sit-down interview with Diane Sawyer on broadcasters CBS’s 60 Minutes discussing her gender transition in 2015 netted an audience bigger than any non-award show or non-sports event in that year.

“What we were seeing was the blurring of lines between reality and news,” Juda Engelmayer, the president of HeraldPR and a crisis communications expert, told Al Jazeera.

On one hand, this introduced once-taboo topics into the conversation. But on the other, it erased the expectation of privacy for non-reality stars.

“What the Kardashians did was make our culture a very confessional one, where we expect people to live out loud in all aspects of their lives,” said Engelmayer. But the flip side of the “no filter” approach has also perpetuated the so-called “cancel culture”.

“Say you’re someone who likes sharing recipes online. You have a blog or an Instagram account. Now all of a sudden, you’re a content creator,” he explained. “And there’s this expectation that because you put one part of yourself out there, people can then dig into your private life and share anything they find.”

While the Kardashians’ fame and fortune could help them rise above this fray, Engelmayer wonders if the dark side of the Kardashians’ legacy is erasing privacy for those who did not want to live their lives in the spotlight.

That said, Engelmayer admits that this spotlight effect has also become the great equalizer.

“Social media has made it possible for anyone to become famous. Before, there were gatekeepers,” he explained. “Now, you can produce content and get eyeballs and you don’t need gatekeepers. But the question is: Will it be fame or notoriety?”

‘Buying a social experience’

The Kardashians are more than stars – they are a brand, notes Dahan. And the way they started to market themselves led to a powerful shift in the way brands began communicating with their fans.

No longer did brands exist only in advertisement agency-approved spots; they interacted in real-time with fans. And a social presence became a baked-in part of any strategy – within and beyond the Kardashian universe.

For example, in 2015 the youngest Kardashian sister, Kylie, launched her beauty brand with a lip kit (a liquid lipstick and pencil) that immediately sold out. Kylie Cosmetics eventually grew into a nearly billion-dollar brand – with some controversy over the exact amount the business is worth.

After Kylie was named “the youngest self-made billionaire of all time” at the age of 21 in 2019 by Forbes, the magazine says she no longer deserves the title – but her net worth is still an estimated $700m.

People buy the products partially because they can then share photos on social media of themselves using them, creating a self-perpetuating marketing loop that has become a standard across diverse goods, experts say.

“Look at Peloton,” said Dahan. “People aren’t buying an exercise bike. They’re buying a social experience. It’s what separates them from the competition. And I think that’s what the Kardashians normalised: the idea that real life happens through social media.”

‘Approval and attention of admirers’

Kim Kardashian – who began the series as a single woman in her mid-20s, famous for a leaked illicit tape, her notorious lawyer father and proximity to Hollywood’s “reality” elite such as Paris Hilton – is now a 40-year-old mother of four, and a law student who advocates for criminal justice reform.

She is worth an estimated $780m, according to Forbes, putting her at number 24 on its America’s Richest Self-Made Women list and number 48 in its Celebrity 100.

People postulate whether she will run for public office. Of course, 13 years produces changes in anyone’s life; the difference is that we feel we have experienced Kim Kardashian’s transformation alongside her.

Unlike past reality stars, who tended to follow one storyline, the Kardashians allowed messy, real life to play out – and there is no question they have shifted our experience and expectations of the world and people around us.

“Proof of its ubiquity is the fact that this Kardashian culture has wormed its way all the way to the British royal family,” Daniel Levine, the director of the Avant-Guide Institute, a business consultancy focused on trends, told Al Jazeera.

“Like the Kardashians, the royal family is keenly aware that their very existence relies on the approval and attention of admirers,” he said. “This codependency is directly responsible for the very public airing of the family’s current difficulties.”

In other words: thanks to the Kardashians, the camera is always on.