Musk defends his $56bn pay package at Tesla

Musk told a court that he was ‘completely focused’ on reviving a struggling Tesla in 2017 when his pay package was set.

Elon Musk has told a court he was completely focused on Tesla in 2017 when the electric car maker was in “crisis”, as he tried to rebut claims that his $56bn pay package was based on easy performance targets and approved by a compliant board of directors.

Tesla shareholder Richard Tornetta sued Musk and the board in 2018 and hopes to prove that Musk used his dominance over Tesla’s board to dictate terms of the package, which did not require him to work at Tesla full time.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTesla cuts prices in China to boost demand

Tesla stock hits two-year low after boss Musk sells more shares

Fake Trump, Bush, Tesla storm Twitter after verification dropped

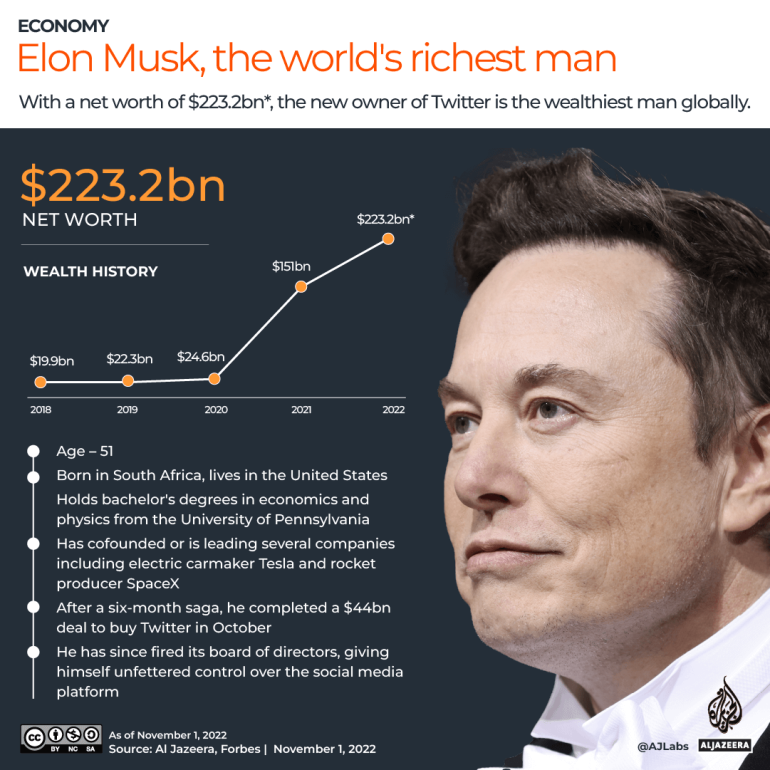

On Wednesday Musk, the world’s richest person, appeared in a courtroom in Delaware in the United States and described how the automaker was struggling to survive in 2017 when the pay package was developed.

Questioned by Tornetta’s lawyer, Greg Varallo, Musk rejected claims that his pay package goals were easy to achieve.

“The amount of pain, no words can express,” Musk said in a near-whisper, describing the effort required to get the company from the brink of failure in 2017 to explosive growth. “It’s pain I would not wish to inflict upon anyone.”

Varallo repeatedly sought to portray Tesla as a company under the grip of Musk and tried to show that Musk bypassed Tesla’s board on several occasions.

For instance, Musk said he made a unilateral call on ending Tesla’s acceptance of Bitcoin cryptocurrency and acknowledged that the board was not informed before he told analysts in October the board was considering buying back up to $10bn of stock.

But the testimony did not definitely prove who developed Musk’s 2018 pay package or establish whether it was a product of his demands rather than negotiations with the board.

In his testimony, Musk said he would not accept a pay plan that required him to punch a clock or commit certain hours to Tesla.

“I pretty much work all the time,” he said. “I don’t know what a punch clock would achieve.”

Combative testimony

The five-day trial before Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick comes as Musk is struggling to oversee a chaotic overhaul of Twitter, the social media platform he was forced to buy for $44bn in October after a separate legal battle before the same judge after trying to back out of that deal.

Musk, who arrived in a black Tesla and was led into the courtroom via a separate entrance due to safety concerns, completed his testimony in less than three hours. He was followed on the stand by Antonio Gracias, a Tesla board member from 2007 to 2021.

The billionaire testified that he focuses his attention where it is needed most, which in 2017 was Tesla.

“So in times of crisis, allocation changes to where the crisis is,” said Musk.

Musk has a history of combative testimony and often appears disdainful of lawyers who ask probing questions. In past trials, he has called opposing lawyers “reprehensible”, questioned their happiness and accused them of “extortion”.

Musk was more restrained in Wednesday’s proceedings, although he chafed at probing questions.

At one point, Musk told the plaintiff’s lawyer: “Your question is a complex question that is commonly used to mislead people.”

Musk acknowledged he was not a lawyer but added, “when you’re in enough lawsuits you pick up a few things”.

Distracted by Twitter

Musk tweeted this week that he was remaining at Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters around the clock until he fixed the company’s problems and said on Wednesday he had come on an overnight flight from the social media company.

In his testimony Musk also said he expected to reduce his time at Twitter and eventually find a new leader to run the social media company, adding that he hoped to complete an organisational restructuring this week.

Tesla investors have been increasingly concerned about the time that Musk is devoting to turning around Twitter.

Shares of Tesla fell 3 percent at midday.

“There’s an initial burst of activity needed post-acquisition to reorganise the company,” Musk said in his testimony. “But then I expect to reduce my time at Twitter.”

Musk also admitted that some Tesla engineers were assisting in evaluating Twitter’s engineering teams but he said it was on a “voluntary basis” and “after-hours”.

Audacious goals

Tornetta has asked the court to rescind the 2018 package, which his lawyer Greg Varallo said was $20bn larger than the annual gross domestic product (GDP) of the state of Delaware.

The legal team for Musk and the Tesla directors have cast the pay package as a set of audacious goals that worked by driving tenfold growth in Tesla’s stock value to more than $600bn from about $50bn.

They have argued the plan was developed by independent board members, advised by outside professionals and created with input from large shareholders.

Tornetta’s lawyer tried to show Musk was involved from the start. An email from May 2017 appeared to establish that Musk was pushing for the pay plan months before the board negotiated it with him.

“I’m planning something really crazy, but also high risk,” he wrote.

Antonio Gracias, a venture capital investor and longtime friend of Musk who was also a Tesla board member from 2007 to 2021, took the stand after Musk testified.

Gracias said he was prepared to push back on Musk if necessary. “I don’t pull punches with any of my CEOs,” he told the court.

The disputed Tesla package allows Musk to buy one percent of Tesla’s stock at a deep discount each time escalating performance and financial targets are met. Otherwise, Musk gets nothing.

Tesla has hit 11 of the 12 targets, according to court papers.

Shareholders generally cannot challenge executive compensation because courts typically defer to the judgement of directors. The Musk case survived a motion to dismiss because it was determined he might be considered a controlling shareholder, which means stricter rules apply.

“There is no case in which a 21.9 percent shareholder who is also the chief executive has received a structured payout plan of this magnitude,” Lawrence Cunningham, a corporate law professor at George Washington University, said of the lack of precedent.