Inside India’s policy flip-flop on wheat exports

India’s policy uncertainty can be traced back to inaccurate crop estimates and poor decisions based on that.

![A woman sorts wheat harvested on the outskirts of Jammu, India on April 28, 2022. India is in the throes of a record-shattering heat wave that is stunting wheat production [File photo: Channi Anand/AP]](/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/indiawheat.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

New Delhi, India – Nearly a decade ago, Harman Brar, now 38, gave up on a career in business management and returned to his ancestral village to take up farming. After years of low crop prices, Brar, like millions of farmers across India, was relieved to see prices of oilseeds and grains soaring through 2021 and surpassing previous highs in March this year, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It was an opportunity to recoup past losses. But late in the evening on May 13 when India banned wheat exports to tame local prices, Brar felt slighted.

“It is the farmers’ interest that is often sacrificed to keep consumer prices low,” Brar said over the phone from his village in Sri Ganganagar in Rajasthan state of northern India.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS, banks unveil plan to address global food crisis

Russia says opening Ukraine ports would need review of sanctions

‘Brink of starvation’: Russia pressed to release Ukraine grain

As global wheat prices soared following the Ukraine war, farmers in India sold their harvest at a 10-15 percent premium over the government’s announced minimum support price. Many held on to their produce, expecting prices to rise further even as traders bought quality harvest in a frenzy.

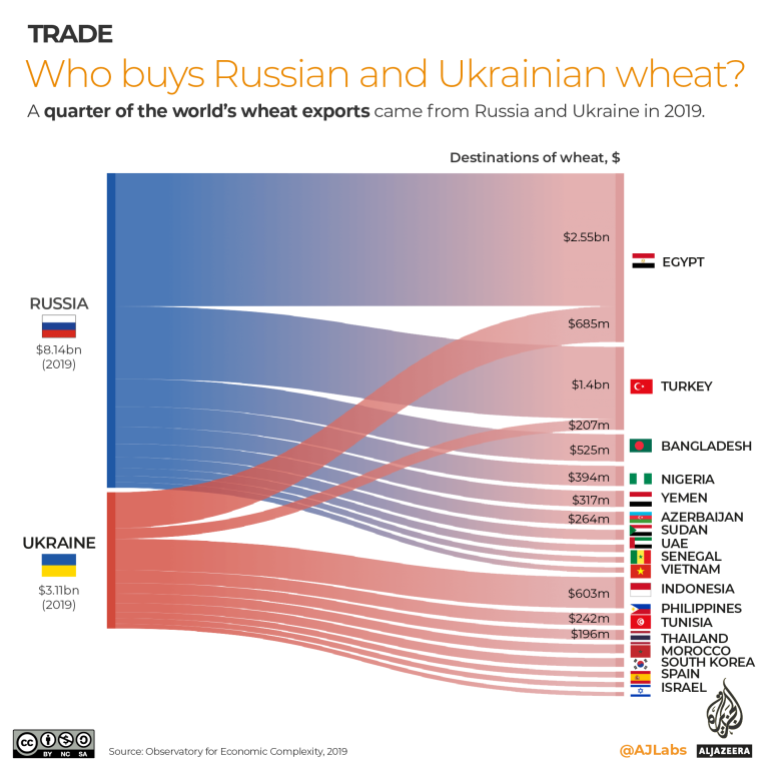

The bullishness was driven by India’s exuberance, with none other than Prime Minister Narendra Modi claiming India is capable of feeding the world and filling the gap created by the Ukraine war. India, the second-largest producer of wheat globally, exported 8.2 million tonnes in the year to March 2022, a record. The government claimed India could export anywhere between 10 and 15 million tonnes in the current fiscal year which ends March 2023. So far, less than five million tonnes have been contracted for exports.

Following the sudden ban on exports announced on a Friday evening, local wholesale prices fell marginally but are still significantly higher than state support prices, an ominous sign indicating the harvest is smaller than estimated. Global prices, however, soared to new highs, with Chicago futures rising by 5.9 percent, the maximum allowed, when trading resumed on Monday, May 16.

“Export ban wasn’t the only solution,” argued Brar. “The government could, and still can, announce a bonus to farmers to mop up supplies. Those stocks can be used later to keep consumer prices in check.” A bonus is a premium paid to farmers, over and above the government-mandated support prices, to match market prices.

It’s not just the farmers that are impacted by the ban. Small traders supplying to large exporters are staring at huge losses after purchasing wheat at a premium and transporting it to ports. Several exporters have refused to unload trucks and honour contracts, invoking the force majeure clause. For now, only export contracts backed by irrevocable letters of credit from banks are exempted from the ban.

The knee-jerk decision came after the government failed to purchase enough wheat for its massive food security program – about 18 million tonnes compared with nearly 44 million tonnes last year. That was largely due to buoyant exports and a lower harvest following an unusually hot March impacting yields. Rising food inflation also pushed it to take a U-turn. In April, food prices surged 8.4 percent year-on-year, while overall retail inflation climbed to an eight-year high. Wholesale wheat prices rose by 10.7 percent in April, maintaining the strike rate of double-digit growth since November last year.

The ban flies in the face of reform laws that the Modi government enacted in 2020, promising farmers unhindered access to markets and minimum state control. (A protracted protest by farmers forced the government to withdraw the laws a year later.)

Inaccurate crop estimates

India’s policy flip-flop can be traced back to inaccurate crop estimates, one that it never acknowledged or fixed, experts said. For instance, in mid-February, the wheat crop was estimated at a record 111 million tonnes by the agriculture ministry, before a heatwave blighted the harvest. But that erroneous early estimate is what the food and commerce ministries had at their disposal for domestic food management and export policies.

In early May, the food secretary said the crop size is likely to be lower at 105 million tonnes. On May 19, the agriculture ministry revised its estimates to 106.4 million tonnes.

Even the latest production estimate is far removed from on-the-ground reality, said Sandeep Bansal, a flour miller in Uttar Pradesh, the largest wheat-growing state in India. “We are expecting a crop size lower than 95 million tonnes. The wide gap between official estimates and actual production is showing up in prices and is the reason why wheat prices did not crash after exports were banned,” he told Al Jazeera

To be sure, the ban is not the only step India took to secure wheat supplies and keep domestic prices in check. It also reduced the allocation of wheat under the food subsidy program and substituted a chunk of it with public stocks of rice, which are in surplus. About 11 million tonnes of wheat saved this way is likely to be used to cool market prices later or for government-to-government exports which are exempted from the ban. “But it won’t be easy to tinker with diets. If subsidised wheat isn’t available, families will likely purchase it from the market, driving prices higher,” Bansal added.

There is a saying among commodity traders – buy the rumour, sell the fact, said Siraj Chaudhry, chief executive of National Commodities Management Services Ltd, which provides services to store, transport, test, trade food and other commodities. “All the talk about feeding the world pumped up sentiments. That bullishness was broken by the export ban but prices did not correct sharply.”

India, he added, will still be prone to many uncertainties, from tight global supplies to surging energy and fertiliser prices providing a tailwind to local food prices. “And if cooking oil prices continue to stay firm, more Indian farmers might plant oilseeds during the winter crop season instead of wheat due to higher profitability and lower policy risks,” he warned.

India is not ‘a dinosaur’

Global hunger levels are at a new high, with the number of severely food-insecure people doubling, from 135 million pre-pandemic to 276 million today, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ told the Global Food Security Call to Action ministerial meeting on May 18. “There should be no restrictions on exports, and surpluses must be made available to those most in need,” he said.

That is easier said than done. For instance, India’s decision to ban wheat exports is part of a wave of protectionism sweeping the world which was accentuated by the Ukraine war. China, for one, has been on a food import spree for more than a year besides restricting exports of fertilisers. Indonesia banned exports of palm oil in April to cool local prices – it was lifted from May 23. Hit by a drought and runaway inflation, Argentina, the world’s top exporter of soy oil and meal, hiked export taxes in March.

“If every country begins to impose export controls, global trade will go into a tailspin,” said Chaudhry. “But India, by leaving the door open for government-to-government exports can now indulge in food diplomacy to its advantage.”

There is still a chance that India could relax its export curbs. In an interview on Sunday, food and trade minister Piyush Goyal told news channel India Today that while the step was to ensure fair distribution of grains to countries in need, rather than allowing speculators to manipulate the market, the government was “responsive” to changing times and was not like a “dinosaur” on any issue.

“We encourage governments to talk to us and wherever we can, we are ready and willing to support.”