China’s Pacific tour spurs hopes and fears in tiny island nations

Countries such as Vanuatu and Kiribati expected to seek Wang Yi’s support for development and infrastructure.

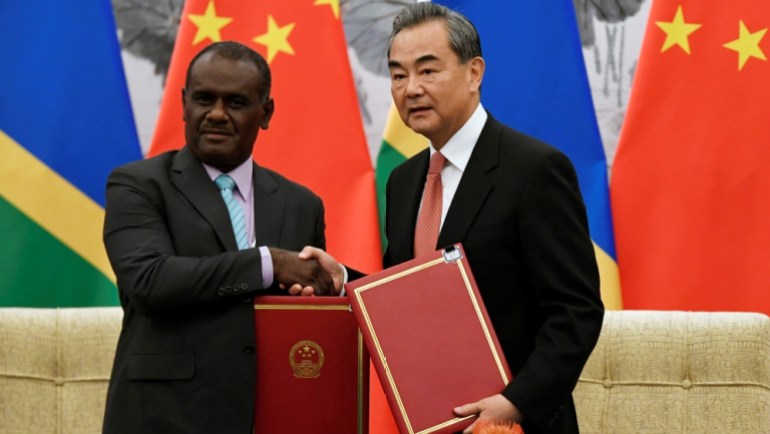

At a carefully choreographed press conference in the Solomon Islands capital of Honiara, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made a promise that will be bookmarked by diplomats and analysts in capitals around the world. Beijing, he said, had “no intention” of building a military base in the Pacific nation.

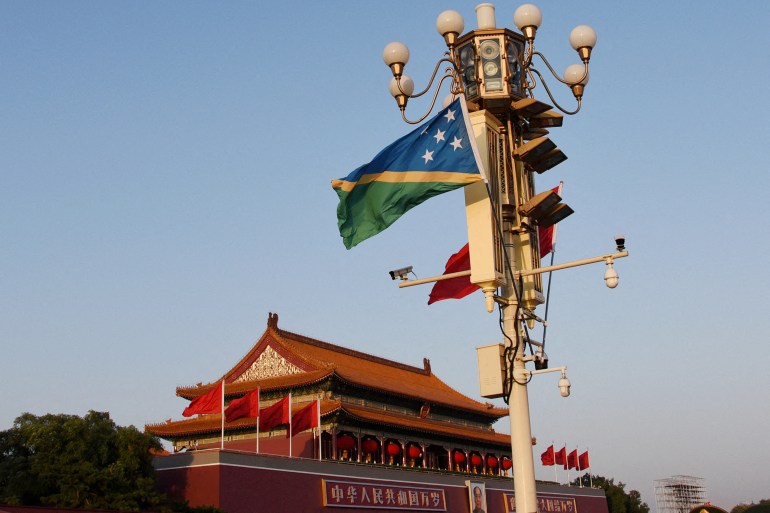

A month after China and the Solomon Islands signed a security agreement, sparking concerns in the United States and its allies, Wang on Thursday embarked on a 10-day tour of eight Pacific nations that also includes Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu, Kiribati, Tonga, Papua New Guinea and East Timor. His visit is the latest chapter in an intensifying geopolitical race to woo the region’s nations. Anthony Blinken, the US secretary of state, visited Fiji in February and Australia’s new Foreign Minister Penny Wong landed in Suva on Thursday.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS stocks jump as solid outlooks from retailers boost confidence

Iraq passes law to criminalise relations with Israel

Despite pain at the pump, Americans are hitting the road

But even though Wang scotched suggestions of a military facility in the Solomon Islands, a veil of secrecy and opacity over specific Chinese plans — heightened by restrictions on the press covering his visit in Honiara — has led to a series of unanswered questions in the region.

Does the security pact with the Solomon Islands allow Beijing to send warships to Honiara, as a leaked draft suggests? Is China pressuring other Pacific Island nations to sign on to a regional version of that agreement, as another leaked memo indicates? Will a proposed agreement on developing the “blue economy” of the Solomon Islands allow China to exploit undersea minerals, as a third leaked document portends? On Thursday, the government in Honiara said that China and the Solomon Islands were “expected to sign a number of cooperation agreements” during Wang’s visit.

On Friday, the Solomon Islands government confirmed the sides had signed a number of agreements related to visa waivers for diplomats and officials, civil aviation, disaster risk reduction and health cooperation. The texts of the agreements have not been publicly released.

“There is a lot of suspicion and distrust between the people and the government on what China is planning to do in terms of development,” Michael Salini, a businessman and commentator based in Tulagi, Solomon Islands, told Al Jazeera. “No one really knows what is on offer from the Chinese side.”

Some things are clear, though. Since 2009, China has been the second-biggest lender to the region, committing a total of $169m, including grants.

Unlike the US and its allies like Australia, or international bodies like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB), Beijing usually does not tie its aid to economic and governance reforms.

“That allows China to say that its loans and grants come without strings attached — even though there are always political considerations involved,” said Peter Kenilorea Jr, an opposition member of parliament in the Solomon Islands.

“This makes China an attractive economic partner for our resource-strapped countries.”

On this trip too, governments of Pacific Island nations are expected to seek Chinese support on everything from infrastructure projects to the post-pandemic recovery of their fragile economies.

Willie Jimmy, a former Vanuatu finance minister and ambassador to China, said he welcomed Wang’s visit, although he had not been previously aware of the trip due to a lack of media publicity or government announcements.

“I welcome any other projects that anyone wishes to announce to help the government and the people of Vanuatu because other donors don’t pick up any projects not in accordance with their foreign policy aid [objectives]. China is picking up those,” Jimmy told Al Jazeera, adding that road building and other infrastructure development in the archipelago, which includes 65 inhabited islands, is difficult due to its scattered island terrain and localised politics.

“That is most welcome by the people. I support China’s initiative to develop the infrastructure of the Pacific Islands.”

Jimmy dismissed fears of so-called debt-trap diplomacy, saying that as finance chief he had persuaded China to forgive 1 billion Vanuatu vatu ($8.6m) in debt after the government was unable to make repayments for two 20-seater Harbin Y-12 aircraft.

“ADB, IMF, World Bank or any other donor cannot do it,” he said. “That’s why I don’t believe in this debt trap.”

Many of the region’s countries are deeply indebted to China.

Vanuatu’s debt to China is almost a quarter of its gross domestic product (GDP), according to AidData, an American research group that tracks how much different governments owe to others.

“Significant debt forgiveness is a hot topic to ease the fiscal burden,” Glen Craig, managing partner at Vanuatu-based Pacific Advisory and chairman of the Vanuatu Business Resilience Council, told Al Jazeera.

Wang’s visit has not been publicised in Vanuatu, he said.

“Generally I think it will be viewed as a sign of the importance of the nation.”

Across the region, recovery from COVID-19 is also a priority, said Sandra Tarte, director of the Politics and International Affairs Program at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

“The Chinese foreign minister may be asked what China can do to aid and support countries as this time — bearing in mind China itself is still experiencing major Covid-induced disruption,” Tarte told Al Jazeera.

But there is mounting scepticism in the region over China’s insistence that its intentions are benign. A Chinese-backed plan to develop a World War II-era airstrip in Kiribati has sparked concerns that Beijing might be planning a base there — though the island nation’s government has denied that there is any such proposal. Last week, the Financial Times reported that China is in talks with the governments of both Kiribati and Vanuatu for security pacts.

Brian Orme, a former opposition spokesperson in Kiribati, said that current President Taneti Maamau enjoys broad public support and would be politically able to push through a security deal with China if he wanted to. Orme said he believes China intends to potentially set up two bases in Kiribati — a move that the US would almost certainly view as a provocation.

“China wants our waters, our deep sea minerals and wants these islands to be close to the United States,” Orme told Al Jazeera.

“Anything China wants, China will get this Friday,” he added, referring to Wang’s visit to the country today.

“There’s no real opposition party. A little bit of noise, but there’s no real opposition party at all.”

China’s security presence is not the only thing worrying some in the region. Kenilorea Jr, the Solomon Islands opposition legislator, said he was concerned about a memorandum of understanding with Beijing focused on allowing China access to his country’s waters.

“Sure, developing the Solomon Islands blue economy would bring revenue, but I’m worried about the depletion of our mineral and fishing resources,” he told Al Jazeera.

The US and its allies are not standing by. Apart from the visits to the region by Blinken and now Wong, the leaders of the US and Australia also met with their counterparts from India and Japan for a session of the Quad grouping in Tokyo early this week. “It’s not lost on me that Wang is visiting when he is,” Kenilorea Jr said.

That geopolitical competition between the US and its allies on the one hand and China on the other could in theory help Pacific island nations strike the best deals. But in reality, said Tarte, the region needs Washington and Beijing to work together on its most pressing concern: climate change.

“In this sense the geopolitical rivalry and competition is not serving anyone’s interests,” she said.