Philippines’ infrastructure woes in focus as Marcos takes reins

Archipelago has for decades struggled to provide adequate infrastructure to serve the needs of its 110 million people.

Manila, Philippines – As a young engineer in the early 1980s, Edgardo Perea worked on a project that he hoped would bring a reliable supply of clean water to households throughout Metro Manila. Forty years later, he is still waiting.

Perea worked at Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System, a government body, as part of a team that carried out preliminary work on a dam that he and his colleagues hoped would take advantage of the area’s vast resources of freshwater.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS kills ‘senior leader’ of al-Qaeda-linked group in Syria

G7, UN condemn ‘deplorable’ Russian attack on Ukraine mall

In Indonesia, ‘pay later’ services leave some drowning in debt

“All the feasibility studies were done, all it needed was implementation,” Perea told Al Jazeera.

But politics got in the way. In 1986, the Philippines People Power revolution led to the removal of dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Under the new government, many projects that had been approved under the previous regime languished or were cancelled altogether.

Perea has been thinking about his experiences a lot these days as his country prepares for another transfer of power, while many of the old problems linger. Besides being deeply personal, they are emblematic of the struggles to improve infrastructure in the Philippines, an archipelago of about 110 million people, where many people still live without basic amenities. In an added layer of irony, the incoming president is the son of the ruler who was pushed out 40 years ago.

New President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, known commonly by the nickname Bongbong, will take office on June 30. His predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, made infrastructure a key policy as part of an initiative he called Build, Build, Build. Duterte promised that the programme would create jobs and improve the quality of life for many Filipinos for whom severe traffic jams and other inconveniences are a fact of life.

Duterte, who described spotty infrastructure as the “Achilles’ heel” of Philippine economic development, pledged to allocate between 8 and 9 trillion Philippine pesos to the programme he said would usher in a “golden age of infrastructure,” adding bridges and railways while expanding a major airport north of Manila.

Filipino voters and political analysts are not sure how Marcos Jr will govern. Throughout his election campaign, he invoked nostalgia for what some Filipinos, accurately or otherwise, think of as a happy time under his father’s rule. But he has been short on policy specifics, leaving unanswered the question of whether he will continue Duterte’s infrastructure drive as he gets set to start his term.

Duterte has called on the new president to continue with Build, Build, Build and the Asian Development Bank has pledged to continue supporting the initiative even with the change of administration.

The programme has a mixed record, with some analysts arguing that it made helpful improvements to under-served parts of the country, while others contend that it fell far short of its objectives.

Ronald U Mendoza, dean of the School of Government at Ateneo de Manila University, said Philippine politicians use public infrastructure to show voters that they have “brought home the bacon,” though the longer-term desirability of such projects is questionable.

“During an infrastructure boom – not just Marcos’s but also Duterte’s – the effect on various parts of the country is stimulative and job-creating … Hence it is much welcomed by citizens and quite palpable and visible,” Mendoza told Al Jazeera.

“It is easy to be nostalgic about an infrastructure boom when you fail to appreciate the crisis and difficulty that is associated with the bad decisions and corruption during the spending part of that debt-fuelled experience. If there’s bad governance and bad decisions, then the party has to end at some point.”

Flawed execution

The execution of the ambitious initiative was also flawed, according to Jan Carlo B Punongbayan, an assistant professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.

“Good, though its intention was, Build, Build, Build unfortunately failed to live up to expectations,” Punongbayan told Al Jazeera. “Spending plans that were not well thought out led to repeated changes in the initiative’s project master list. Only a portion of the promised projects was executed.”

The Marcos dynasty also has a reputation for corruption. Observers of Philippine politics worry that such corruption could cloud the next administration.

“Marcos Jr comes from a known kleptocratic family that flourished during the martial law years through crony capitalism,” Punongbayan said. “Hence, he is not expected to do much work to stop corruption and in fact, he may very well worsen it.”

The Philippines ranks poorly on global corruption assessments, coming in 117th out of 180 countries on the most recent ranking by Transparency International. Parts of the Philippine electorate appear to have accepted the stubborn presence of corruption in government and business.

Though Duterte took office depicting himself as a swashbuckling outsider who would pull the plug on corruption, the same elite has retained control of Philippine business, according to analysts.

“Duterte never really intended to root out the old power networks, and I think there is a degree of resignation now,” Josh Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, told Al Jazeera.

Meanwhile, the basic needs of much of the population go unmet. According to the Sustainable Development Goals Fund, “substantial numbers” of people suffer water scarcity and access to basic sanitation, putting them at risk of water-borne disease.

A report by the World Health Organization and UNICEF found that just 47 percent of Filipinos had access to safely managed drinking water in 2020, a slight improvement from 46 percent in 2015. The country’s infrastructure challenges are connected to large-scale rural-to-urban migration, as many Filipinos leave the countryside to seek jobs in large cities, particularly Metro Manila, causing severe traffic gridlock that results in exorbitant commuting times and delays in the transport of goods to points of sale.

Perea, the former waterworks engineer, recalls needing to go through a process of getting signatures from government officials in various departments before a project could go ahead.

“That’s where corruption sets in,” he said.

Stung by the failure of the water project he worked on, Perea quickly became disillusioned with the politics of public infrastructure.

“I saw how the system really worked … When the project stopped, I was criticising everything. I said too much and I had to eat my words,” he said. “Some older colleagues took me aside and told me, you cannot fight the system by continually hating it. You have to play the game, get to the top, and then you can make some changes.”

Instead, Perea resigned. After unsuccessful efforts to cross over into private engineering firms, he ran a few small businesses, including a martial arts academy.

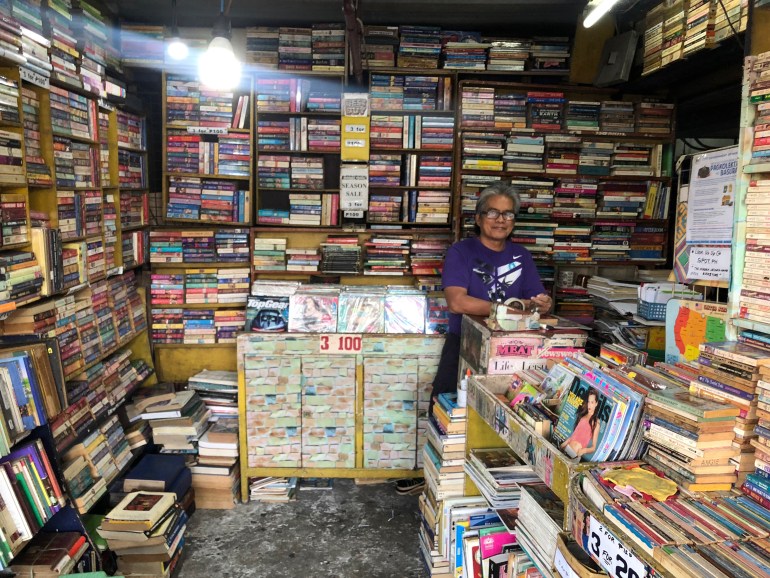

He eventually settled, in the late 1980s, on a less confrontational form of business – a bookstore in a busy commercial area near Manila’s Guadalupe elevated train station. He named the bookstore JERVS, a combination of his five children’s first initials, and found peace running his own shop.

In that pre-internet era, when reading was a more common form of entertainment, Perea found a profitable model renting out novels and magazines. He ran the bookstore until the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Philippine government implemented strict lockdowns that froze much of the country’s street-level commerce.

Over those years, and throughout the hiatus imposed by the pandemic, Perea had time to ponder his country’s political history, including the current moment where the son of a dictator overthrown by a people-power revolution is about to move into the presidential palace.

He does not consider himself a Marcos supporter but hopes the new government will continue to invest in infrastructure as the Duterte administration did. He also understands how the dynasty appealed to voters in a country where many governments have fallen short of solving the same old problems.

“The 1960s and 70s do seem like a golden era for people who lived through war and everything that came before that,” he said.

“These urban legends survive through the generations, and sometimes, they get exaggerated.”