US waged war on China’s chips; S Korea, Taiwan felt the fallout

Washington’s bid for self-sufficiency in semiconductors is complicating relations with its tech-savvy partners in Asia.

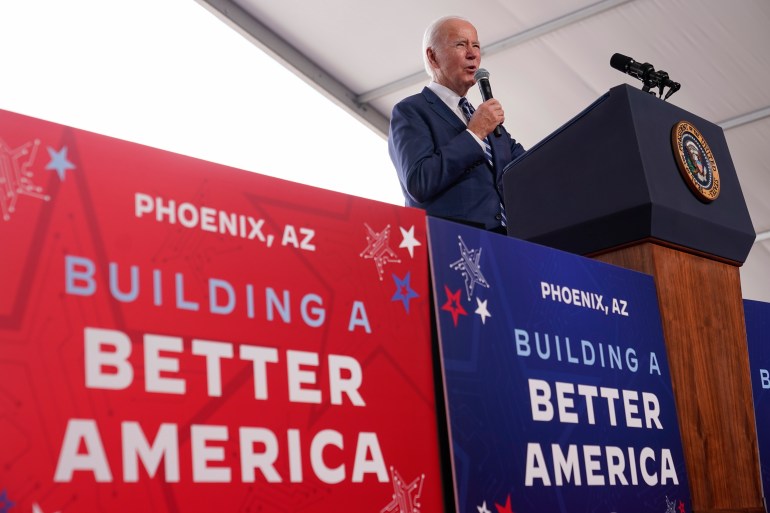

Seoul, South Korea and Taipei, Taiwan – When United States President Joe Biden made his inaugural trip to South Korea as president in May, his first stop was a massive semiconductor production facility operated by Samsung Electronics.

The choice signalled Biden’s recognition of the importance of both Samsung, South Korea’s biggest conglomerate and a major investor in the US, and semiconductors, the chips that power countless modern appliances and sit at the centre of a growing US-China rivalry that encompasses business and geopolitics.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat does the future hold for brain implant technology?

Vietnam eyes China’s tech crown as firms tire of ‘zero COVID’

‘Green’ tech can’t save us from climate change | All Hail

“Semiconductors power our economies and enable our modern lives, from our automobiles to our smartphones to medical diagnostic equipment,” Biden said at the factory before touting chips as the next frontier in the alliance between the US and South Korea that dates back to the 1950-1953 Korean War.

“And by uniting our skills and our technological know-how, it allows the production of chips that are critical to both our countries and are essential – essential – sectors of our global economy.”

But several months removed from that visit, the picture of mutually beneficial cooperation presented by Biden is being complicated by US measures to both restore its own manufacturing base and confront China.

Even as Washington tries to recruit Asian allies and partners to join the pushback against Beijing, its turn towards protectionism has caused jitters in the US-friendly chip powerhouses of South Korea and Taiwan, both of which have close economic links to China.

“To a good extent [the US] is very dependent on everybody, [and] everybody is very dependent on China,” G Dan Hutcheson, vice chair of TechInsights Inc., told Al Jazeera, arguing that while these countries may to an extent see each other as competitors for chip supremacy, their economies rely on trade with each other.

There are scenarios where competition over chips could compel countries to seek leverage by withholding exports of other items, such as electronics or pharmaceuticals, thereby causing broad disruptions to global trade and shortages of consumer goods, Hutcheson said, adding: “This could just become really ugly very fast.”

Biden has stressed the need for measures to boost high-tech manufacturing at home, both to create jobs and reduce reliance on overseas suppliers and the whims of global supply chains.

In August, Biden signed the Chips and Science Act, which highlighted how the US relies on East Asia for 75 percent of its semiconductors. The legislation provides $52.7bn in funding for semiconductor research and is explicit in its intention to “counter China”, the US’s main competitor for economic and military influence globally.

The law includes “guardrails” intended to prevent companies from building production facilities in China and bans US companies from supplying equipment that China could use to produce advanced chips.

In South Korea, Japan and Taiwan, the US push to hobble China’s tech advancement has presented challenges.

South Korea’s Samsung and SK Hynix, which together lead global production of memory chips, and Taiwan’s TSMC, the No 1 player in non-memory chips, all operate production facilities in China.

Japan, another US ally and home to some of the world’s leading semiconductor materials producers and equipment makers, last year exported more than one-third of its manufacturing equipment to China. In a meeting with reporters last year, Kyung Kye-hyun, head of Samsung Electronics’ semiconductor business, expressed concern about “difficulties in the long run when we have to put new equipment into our factory in China”.

Kyung also said South Korea should seek “understanding” from China, the country’s biggest trading partner, before joining a proposed “Chip 4 alliance” comprising the US, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan.

More than a year since it was floated, the nascent alliance, which Biden has championed as a way to foster cooperation in the production and supply of semiconductors, has hammered out few concrete details and held just one preliminary meeting.

Last month, Morris Chang, the 91-year-old founder of TSMC, lamented that globalisation and free trade were “almost dead” and unlikely to come back.

Tsai Yu-tai, a top official at Taiwan’s Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, has also expressed concern that Washington’s actions had created “uncertainty” for the island’s chip industry, although the impact remained unclear.

The Biden administration has acknowledged the need for buy-in from major industry players to hinder China’s technological progress and has granted exemptions from export controls to favoured firms including TSMC and Samsung, although it is unclear how long such exemptions may last.

TSMC, Samsung and SK Hynix have all announced plans to invest in new facilities in the US in recent months, including two new TSMC facilities in Arizona that rank among the biggest foreign-led projects in US history.

TSMC declined to comment. Samsung and SK Hynix did not respond to requests for comment.

For many in South Korean business, the Chips Act added to anguish sparked by Washington’s announcement that South Korean makers of electric vehicles would be excluded from tax breaks granted only to vehicles produced wholly in North America. Hyundai Motor and its affiliate brand Kia both produce EVs in South Korea for export to the US.

Companies, politicians and media outlets have decried the protectionist moves as betraying the spirit of the two countries’ alliance and called on the South Korean government to roll out similarly generous measures to support domestic industry.

“If politicians’ perceptions do not change, our companies will find it difficult to survive the global semiconductor war without gunfire,” argued a recent editorial in the Seoul Economic Daily newspaper, reflecting a common sentiment in a country where industry has traditionally expected the government to help it compete with overseas rivals through the provision of subsidies and tax breaks.

On Wednesday, the administration of President Yoon Suk-yeol announced that the government would increase the tax credit for investment in advanced technology, including semiconductors, from 8 to 15 percent.

Yang Hyang-ja, chair of a special government committee on semiconductors, has called on the government to go further, with more financial support and easing of regulations to make it easier for semiconductor firms to expand their production in South Korea.

She wrote in a Facebook post after the subsidy was announced that she had lobbied the government to enact a 25 percent tax credit, which she says is the minimum to prevent an “exodus” of chipmakers out of South Korea.

In Taiwan, some have expressed concern that the US subsidies could spur a relocation of semiconductor production and erode the country’s so-called Silicon Shield, its base of advanced industrial facilities that some analysts believe could help deter an invasion from China, which claims the self-governing island as its territory.

Chris Miller, author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, told Al Jazeera those concerns are “overblown”, saying that TSMC is opting to keep its cutting-edge production in Taiwan and that “the US can’t replicate what TSMC has done in Taiwan … TSMC’s technology is top notch and the Chips Act funding is unlikely to remove TSMC from its position at the top of the chip industry.”

While TSMC is the undisputed top player in Taiwan, the country also has many smaller companies that make less advanced chips and rely on trade with China. The Chips Act could have the effect of cutting these firms off from the US, some observers say.

“[In] Taiwan, tech firms, such as UMC and other firms are really worried because they don’t make advanced nodes … They are somewhat under the radar, but then I could see them becoming more integrated with the Chinese technology ecosystem,” Jason Hsu, a former member of Taiwan’s parliament with the opposition Kuomintang, which has traditionally favoured warmer ties with Beijing, told Al Jazeera.

Hsu said the Taiwanese public is divided over the situation, with some people resentful towards TSMC’s investments in the US and others believing the company has little choice but to adapt to the industry’s changing contours.

In the near term, the Chips Act is likely to encourage chipmakers to reduce their production in China, though the importance of the Chinese market will mean that companies will seek ways to continue selling their products there, said Lee Jang-sik, a professor of materials science and engineering at Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH).

Such companies are likely to “mobilise various methods, like bypassing The Chips and Science Act, to produce in China or sell to China” while building more fabs in the US, Japan, Europe and elsewhere, Lee told Al Jazeera.

Other analysts have also cautioned American policymakers against protectionist measures, arguing that the semiconductor industry relies on the trade of highly specific high-tech items, and insisting on domestic production can lead to the misallocation of resources.

“US self-sufficiency is an illusion,” said a policy brief by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The United States currently exports high-value chips and imports low-value chips, so increasing self-sufficiency would require the United States to prioritise basic chip production at the same time it is supposed to be competing with China in advanced chip production.”

The development of advanced chips also relies on collaboration among teams of experts, who may or may not live in the same country.

“The most cutting edge semiconductors require over a thousand process steps, and no single individual is an expert at each step,” Miller said, adding: “So chipmakers need to access lots of unique expertise to fabricate advanced chips.”

Lee, the POSTECH professor, said that after the dust settles with the chip industry’s ongoing reorganisation, companies and governments will be forced to respond to the need to operate more cheaply than competitors.

“In the long term, the biggest driving force of semiconductor companies is cost reduction, and through this, semiconductors have continued to innovate and made great progress,” he said.

“The most important thing is production cost… No matter how large the tax benefit is.”