Cambodia’s bloggerati fear new Internet law

Bloggers and campaigners in Cambodia warn that new law is intended to thwart online debate.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia – Once a week, Ou Ritthy and a circle of young, like-minded netizens pick a shop from the capital’s burgeoning selection of trendy cafés and come together to debate the latest apps, gadgets, social media trends – and politics.

One of Cambodia’s best-known bloggers, Ritthy has been hosting this “politikoffee” since 2011.

He described the crowd as “a group of young, enthusiastic and social media-savvy Cambodians who love sociopolitical and economic discussion”, and “believe in liberal democracy prevailing in Cambodia by enhancing discussion and debate”.

With their help, that debate is moving increasingly online. The Ministry of Post and Telecommunications recently said 3.8 million of the country’s roughly 15 million people were using the Internet in 2013, a 42.7 percent jump from the previous year. In 2011, Internet use skyrocketed more than 500 percent.

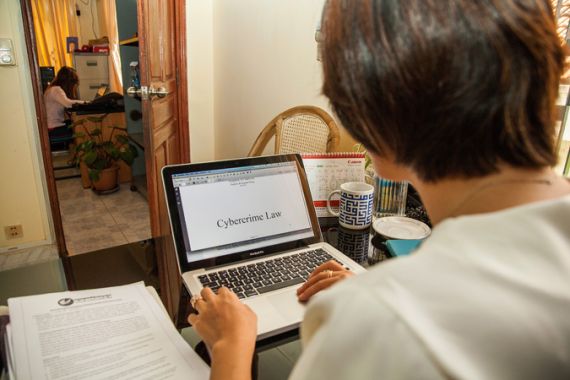

But a leaked draft of the government’s Cybercrime Law has bloggers such as those in Ritthy’s group worried that Prime Minister Hun Sen and his long-ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) are cutting off one of the last remaining outlets for political debate in the country.

If this draft law is passed, my peers and I will be more cautious with our political expression despite the fact that we have never defamed or abused any ruling official.

“If this draft law is passed, my peers and I will be more cautious with our political expression despite the fact that we have never defamed or abused any ruling official,” Ritthy told Al Jazeera. “E-democracy has just [been] born in Cambodia, but this cyber law will be undermining its process.”

‘Hindering integrity’

The 16-page draft lays out penalties for everything from computer fraud to online spying and child pornography.

But what its critics fear most is Article 28, which would make it illegal to publish any content seen to “hinder the sovereignty and integrity” of the country, “incite or instigate the general population”, or “generate insecurity, instability and political [in]cohesiveness”. It would ban any content deemed “non-factual which slanders or undermine[s] the integrity of any government agencies”, or is damaging to the country’s “moral and cultural values”.

Perpetrators could face up to three years in jail.

Article 19, the London-based advocacy group that leaked the draft law last month, said its wording was “extremely vague and open to abuse”, and the law could be used to criminalise “many legitimate forms of online expression that challenge corruption or wrongdoing by the authorities or are simply critical of the government”.

Naly Pilorge, director of Cambodia’s human rights group Licadho, agreed. “It’s quite clear that activists, media, NGOs and others are targeted in this draft law,” she told Al Jazeera.

Critics are also concerned the law would have the serving prime minister chair the committee charged with implementing it.

Phu Leewood has spent a decade heading Cambodia’s National Information Communication Technology Development Authority, and now advises the government on IT issues.

Whoever proposed putting Prime Minister Hun Sen in charge of the law’s oversight committee may have been trying to curry favour and deter any parliamentary opposition to the bill, he told Al Jazeera. He also called the draft “irresponsible” for doing away with checks and balances that should come with enforcing a cybercrime law.

|

| Prime Minister Hun Sen at a ceremony in January [Reuters] |

“You are concentrating power in one man’s hands, so you are repeating history,” he said.

Leewood likened the draft law to the US Patriot Act passed in the wake of the 2001 September 11 attacks on the United States – legislation that has since been rebuked by civil liberties groups.

“The content of the Patriot Act is essentially removing individual constitutional rights,” he said, adding a better name for it would be the “Denying Individuals Constitutional Rights Act”.

With this Cybercrime Law, he added, “the same is true for Cambodia”.

‘World Telecommunications Organisation’

The government won’t say how quickly it wants to move on the law.

Post and Telecommunications Minister Prak Sokhon could not be reached for comment after several attempts. Ou Phannarith, who heads the ministry’s information and communications technology security department, declined to comment.

Council of Ministers spokesman Phay Siphan told Al Jazeera the law was meant only “to protect private interest from groups who want to destroy and cause public damage”.

Rights groups are asking the government to officially release its latest draft of the law and take public comment. However, Siphan said the government had no legal obligation to do so.

“We consult with the international experts… because we have a democratic society,” he said. “We seek experts, not activists.”

For advice, he said the drafters turned to the “World Telecommunications Organisation… the WTO”. No record of such a group could be found, however.

Since national elections last July, the National Assembly has functioned with barely half of its 123 seats filled. Lawmakers who have taken their seats all belong to Hun Sen’s ruling CPP, which officially won the vote, while the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) lawmakers are boycotting the assembly in protest over what they say was a stolen election.

With nearly half the country’s voters not represented in the assembly, campaigners are urging it not to consider the Cybercrime Law until the opposition takes its seats.

The opposition insists it won the electionand an independent audit of the vote, which the CPP is against, would prove it. But even by the government’s own count, the CPP was handed its worst electoral bruising in more than 20 years of power.

|

| Protests have increasingly been organised online [Reuters] |

Ritthy, the political blogger, called last year’s elections “a historic moment [for] e-democratisation in Cambodia” with the opposition and young Cambodians taking to social media to rally support in unprecedented numbers. So much so, he said, many were calling the CNRP the “Facebook Party”.

They used social media to help bring more than 100,000 Cambodians out on the streets in support of CNRP president Sam Rainsy’s return to the country just before the elections, after years of self-imposed exile.

Demonstrations were largely ignored by mainstream media, but online, Ritthy said, “information about politics, the elections and electoral irregularities spread like wildfire among voters, triggering social dissatisfaction and leading to mass demonstrations.

“Social media, especially Facebook, has made [the] CNRP more interesting, lively, updated and relevant to youth, and the young inform their families and… communities.”

‘Bad examples’

According to the official count, the CPP held on to power by less than 300,000 votes. The Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia, a local election monitor, said at least that many new names will be added to the voter rolls each year between now and the next elections in 2018 – the vast majority tech-savvy and too young to have lived through the Khmer Rouge era or the civil war that followed.

Ritthy said those voters will be “game changers” in 2018.

With the proposed Cybercrime Law, Cambodia could be moving towards the approach taken by some of its neighbours, said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch.

The monopoly over the national TV and radio, and much of the printed press, doesn't mean as much as it did when more and more Cambodian youth are going online to learn what is happening.

“There are plenty of other bad examples in the neighbourhood, such as China and Vietnam, who can show Cambodia how to go about building trumped-up cases to prosecute bloggers and online activists,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Going after opposition political figures and their supporters is entirely possible,” Robertson said. “I’d expect that a couple of high-profile prosecutions of opposition bloggers could be used to try and intimidate others to self-censor what they are saying; that seems to be the pattern.”

In Cambodia, he said, “The monopoly over the national TV and radio, and much of the printed press, doesn’t mean as much as it did when more and more Cambodian youth are going online to learn what is happening. That’s the thing that has got the Cambodian government worried.”

When independent trade unions representing some of the country’s 600,000 garment workers wanted to organise a strike last month for higher wages, they went online when police started confiscating their flyers and threatening to arrest those handing them out.

A group of young Buddhist monks, meanwhile, has started filming its own news show about forced evictions and government land grabs and posting their clips on Facebook.

Passing the Cybercrime Law as it stands, Pilorge said, “would be the final step to close off any democratic space left in Cambodia”.