China’s cancer doctor for the very sick and very rich

Dr Xu Kecheng wanted to find a way for advanced-stage cancer patients to live with the disease rather than die from it.

Beijing, China – As she waited to see her oncologist, Raluca Pietroiu felt nervous but hopeful.

For four years, the 34-year-old Romanian marketing executive had been fighting breast cancer. She knew she was a fighter – she’d grown up watching Jackie Chan movies and had fought hard for her professional success. But in the battle for her life, she was starting to feel like she might be losing.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPoland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

First pig kidney in a human: Is this the future of transplants?

Why are some countries decriminalising drugs?

At first, treatments made her cancer disappear, but after two years it returned. Now it was spreading to her bones. Doctors told her that they were running out of options. But Pietroiu had a new reason to hope: She’d heard about a hospital in China that was treating advanced-stage cancer patients like her with immunotherapy and other new procedures.

Immunotherapy, a treatment that uses the body’s own immune system to attack cancer cells, has proven highly effective in certain cancers, such as melanoma. But forms of immunotherapy are still labelled experimental in many places, including the United States and Western Europe, and the treatment isn’t available in Romania.

Pietroiu knew her doctor would be sceptical. After all, she’d already pursued treatments in Austria, France and Turkey. But this time, it was different.

Her stage 4 cancer was unresponsive to chemotherapy and radiation. She thought she was playing her last card in the game against death.

“If it’s immunotherapy and you can afford it, by all means, go ahead,” her doctor told her.

Heading to China

So, in February 2015, Pietroiu arrived at Fuda Cancer Hospital in Guangzhou in China’s Guangdong province.

According to its president, Niu Lizhi, the hospital treats about 3,000 patients a year, 90 percent of whom have advanced forms of the disease.

“For most patients, it’s just palliative treatment because [their disease is] late-stage and middle-stage and cannot be cured,” Niu explained. “I think maybe 10 percent of our patients, who are at an early stage, can be cured with long-term results. But with the new treatments, even some of the patients with late-stage cancer can survive for a long time due to the new medicines, new techniques.”

More than half are foreigners, explained the hospital’s founder, Xu Kecheng. They fly in from Europe, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, India and North America looking for a new chance at treatment – and life.

![The main entrance to one of Fuda Cancer Hospital's two campuses [Simina Mistreanu/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/4a6daaca95eb41d69994d14668a3040b_6.jpeg)

Hope and science

According to the hospital’s website, it uses a combination of immunotherapy, minimally invasive treatments and traditional Chinese medicine to make advanced-stage cancer patients comfortable and to possibly extend their lives.

And while the hospital’s model has attracted awards from the Chinese government and praise from other doctors in the region, some Western health professionals have questioned the treatment’s grounding in science, as well as the hospital’s lack of randomised clinical trials.

The treatments cost in the range of tens of thousands of dollars. But about a dozen patients and family members interviewed expressed gratitude at what they perceived as a second chance at life or, at least, an opportunity to extend it by a matter of months or years.

“I think you should never take hope away from the patient,” said Gurli Gregersen, a Fuda patient who has been living with stage-4 pancreatic cancer for eight years. Doctors in Denmark initially told her she had just a few months left to live.

“You shouldn’t be unrealistic, but it’s very important that you keep up the spirit that you can do it, and you can fight it. They are very skilled when it comes to giving you a realistic view, but they also support you to be happy for your life and to endure everything you can to live with it.”

Pietroiu put it more bluntly: “You go there because you still have hope.”

“Here [in Romania], they close the door in your face, and they tell you, ‘There’s nothing more we can do,’ or ‘Why don’t you continue with the same therapy?’. The treatment protocols are fixed. And in Vienna, even though they treat you very nicely, and they take your money gracefully, they do the same things,” she said.

The doctors don’t promise to cure very advanced cancer, explained Abdalla Gurashi, who is from Sudan and at the hospital with an Egyptian friend who has stage-4 stomach cancer. “There’s no cure. There’s only maintaining.”

Immunotherapies

The discussion around care for the terminally ill is growing more urgent as cancer affects more of us, and in many places, that involves debates around the best practices for palliative and hospice care.

But at the other end of the spectrum of care, new immunotherapies and targeted therapies are yielding results.

While the concept of immunotherapy isn’t new, the breakthrough over the past several years has been the development of medicines that are more tolerable and produce better responses, particularly in melanoma patients, explained Leonard Lichtenfeld, the deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

“What we’re seeing is that with a disease like melanoma, where we had nothing much to offer, we now have 35 to 40 percent of the patients with the most advanced disease responding in a meaningful way to immunotherapy,” Lichtenfeld said. “And some of those patients are now going on several years with the positive responses. We don’t even know how long those responses are going to last.”

Scientists are also seeing results for immunotherapy applied to other types of cancer, such as lung, head, neck, colon and kidney cancer, Lichtenfeld said. They are studying combinations of immunotherapy, as well as immunotherapy combined with targeted drugs, which focus on a particular genetic change.

Poor treatment for the poor

But all of these developments elude patients from some countries.

According to Andre Ilbawi, a technical officer in cancer control at the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters in Geneva, access to quality cancer treatments varies widely. The differences between countries tend to correspond to their income levels, but are also influenced by factors such as awareness of the disease.

“As we look at the heterogeneity of treatment service availability across the world, we recognise that there are novel therapies that are being introduced in high-resource settings that are available to populations there, and then there are vulnerable populations in low-resource settings that don’t have access to even the most basic known high-impact treatment options such as surgery or chemotherapy,” Ilbawi said.

A 2015 Lancet Oncology study found that less than a quarter of new cancer patients worldwide had access to quality affordable surgery, which is considered one of the main cancer treatments, along with chemotherapy and radiation.

As cancer treatments become more expensive and more people suffer from the disease, Ilbawi said there are suggestions that the disparities between countries might be growing.

Against this background, patients with advanced-stage cancer that has become unresponsive to chemotherapy and radiation often find themselves navigating an international map of cancer treatments.

Sometimes their journey takes them to places like Guangzhou.

![Raluca Pietroiu in Zhongshan, China [Simina Mistreanu/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ab231aac7d284c07a5c7be41a6a5824f_6.jpeg)

‘Living with cancer’

The capital of Guangdong province, in south China, sprawls across the Pearl River Delta and around Baiyun Mountain. The tropical city boasts a tradition of medical expertise. Sun Yat-sen, the celebrated father of Chinese democracy, and a doctor, founded one of the city’s major universities, which carries his name.

Fuda Cancer Hospital was established here as a private facility in 2003. Its founder, Xu Kecheng, had previously led a hepatic disease research centre in the nearby city of Shenzhen, where he was also a chief physician.

From his office inside the hospital, 76-year-old Xu explained that he wanted to open a cancer hospital to explore new methods of treatment.

With a ready smile, he listens intently, giving the impression that he has all the time in the world, although his phone rarely stops buzzing.

He had been disillusioned with the global “war on cancer”, ignited in 1971 by then US President Richard Nixon, he explained. In 2004, he read a story in Fortune magazine that resonated with him. The article, titled Why We’re Losing the War on Cancer, centred on how efforts to fight advanced forms of cancer were largely unfruitful.

Xu decided he wanted to explore ways to “live with cancer”.

“Cancer originates in a gene mutation, so it’s actually not an enemy from the outside,” the doctor explained. “It’s not like a bacteria or a virus that invades our body from the outside to produce a disease; it’s a changing of our own cells.”

If the cancer is identified early, then it has high chances of being eradicated from the body. But for many patients, the cancer has recurred or has already spread before its detection. In those cases, fighting it aggressively with chemotherapy and radiation is purposeless, Xu believes.

“It’s like the Americans invading Iraq – you do a lot of damage, but you’re fighting a war you can’t win,” he said.

So Xu decided he would build the hospital around offering palliative treatments to advanced-stage cancer patients, with the aim of making them comfortable and prolonging their lives.

He wanted to use new, minimally invasive procedures, such as cryoablation, which destroys tumours by repeated cycles of freezing and thawing produced by probes inserted into the body; and the NanoKnife, which uses high-voltage current to puncture the membrane of cancer cells.

He paired the minimally invasive treatments with immunotherapy to boost the body’s immune response to cancer, and with transarterial chemoembolisation, where microspheres containing chemo drugs are directed through an artery straight into the tumour, thus increasing the drug concentration that reaches the tumour and reducing the overall side-effects.

The standard treatment at Fuda Cancer Hospital was called “3C P” – which stands for cryosurgical ablation, cancer microsphere intervention, and combined immunotherapy for cancer, as well as a personalised approach. But the specific treatments for each patient are decided by a board of doctors based on their individual case, explained Niu, who is also the hospital’s chief surgeon for minimally invasive surgery.

“My thinking is problem-based medicine,” said Niu. “I first solve the patient’s problem.

“If the patient feels pain, I’ll solve the pain. If the patient cannot eat, I’ll help him to eat. If the patient has a psychological problem, we call in a psychologist. If he has a nutrition problem, we call in the nutritionist. After all these problems have been solved, then the second aim is to prolong the life.”

The treatments are not cheap. Procedures such as cryoablation and immunotherapy cost at least $20,000 each, according to patients.

Yet, despite the costs and its unusual approach, the hospital has thrived: From a 20-bed capacity when it opened in 2003, it has now grown to include 400 beds and a second, 11,000-square-metre facility that opened in 2011. Xu has won a slew of awards from the Chinese government and other institutions, including the Bethune Medal, which is considered China’s highest medical award.

![A common area in Fuda Cancer Hospital's patient ward is decorated with paintings sent by former patients [Simina Mistreanu/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/c7abfb600ebe42d3a4bd0ac1429328dc_18.jpeg)

Yet scepticism about the hospital has lingered through the years. In 2008, a Danish newspaper covered the case of a patient from Copenhagen who sought treatment for her stage-4 pancreatic cancer at Fuda. Ulrik Lassen, the chief physician at Copenhagen University Hospital Unit for Experimental Cancer Treatment, was quoted as saying Fuda’s treatments were “unethical” for offering patients false hope.

And in 2014, when Xu gave a presentation in Perth, Australia, together with an Australian patient, the vice president of a regional chapter of the Australian Medical Association, Andrew Miller, accused Fuda of quackery. Both Lassen and Miller haven’t responded to requests to expand on their concerns.

Gurli Gregersen, the Danish patient profiled in the 2008 story, is still alive today. The 68-year-old retired teacher was diagnosed with stage-4 pancreatic cancer in 2007. She underwent a few rounds of chemotherapy, after which her Danish doctors told her to go home and enjoy the last months of her life with her family.

But Gregersen’s daughter wouldn’t hear about her giving up. She had read a story about Fuda and suggested Gregersen give it a try. The retiree sold her apartment to pay for the treatment and flew to Guangzhou in the spring of 2008. She received cryosurgery, immunotherapy and other treatments, and then flew back home.

“I was just expecting to live a little longer, maybe half a year. I would have been happy,” Gregersen said. “But then I could see I was not tired, I was not getting skinny, and I didn’t have pain. You know, it got better and better.”

Since then, Gregersen has taken annual trips to Fuda for immunotherapy and other minimally invasive procedures. The doctors and nurses there have become her second family, she said.

She now lives an idyllic retiree life – she has a small house in the country outside Copenhagen, where she gardens, knits, takes long walks on the beach, looks after her grandchildren and spends time with her friends visiting museums and art galleries. She even started attending an evening class on Chinese history.

She said her Danish doctors prefer not to discuss her treatments in China, and request that new tests be done even when she brings recent scans from Guangzhou.

Xu is proud to talk about Gregersen’s case. He calls her a “miracle patient”. The doctor takes pride in taking on cases other doctors have deemed untreatable and his office is decorated with gifts from patients and pictures they’ve taken with him.

He opens a book that catalogues some of Fuda’s most famous cases, including patients with visible external tumours: “Before, after; before, after,” he says as he thumbs through the pages.

In January 2006, Xu was himself diagnosed with liver cancer – a disease that also affected his mother and sister. He received surgery and immunotherapy then, but is unaware of his current status. He said he feels great, and he still comes to the office every day.

“Most doctors like to treat early-stage cancer,” Xu said. “But there are larger and larger groups of people who suffer from advanced cancer. Early-stage cancer can’t always be discovered on time. We have no choice but to deal with this matter. These things are very difficult for doctors to do, but I’m willing to try.”

Not losing hope

At Fuda, Pietroiu received immunotherapy as well as an injection with strontium-89, a radioactive substance used to reduce pain in patients with metastatic bone cancer. She didn’t have any serious side-effects and after three weeks, returned home, full of hope.

Her years battling cancer had been some of the most important of her life. When she was in remission, she met Bogdan. They clicked instantly. She told him she was a cancer survivor. A few weeks later, in the spring of 2013, Pietroiu learned during one of her regular checkups that the cancer had reappeared in her spine. Bogdan joined her on some of her visits to hospitals abroad, and every time they tried to make a trip of it.

In February 2015, they married.

![Raluca and Bogdan Pietroiu met during Raluca's remission [Photo Courtesy of Bogdan Pietroiu]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/c1e42dfb24b74f9183e907cb9fdbeb0d_18.jpeg)

After the immunotherapy, she felt better, but tests showed that her liver had been invaded by thousands of tiny metastatic cancer cells. She returned to Fuda with Bogdan in May, two months after her first visit. This time the doctors took several days to suggest a treatment – transarterial chemoembolisation to her liver.

Pietroiu wrote an article for her friends and for people who had started supporting her with donations.

“It won’t be an overnight miracle,” she wrote. “It’s not a one-time intervention, after which I can go back home, and it’s over. The road ahead is longer. I will continue to come here once every two or three months, upon these wonderful doctors’ recommendations, to stabilise my situation if the results are good. If not, I will look for something else, but I won’t stop.”

Scientific standards

Part of Fuda’s appeal to patients is the fact that the palliative care offered, especially immunotherapy, has the potential of extending life. Immunotherapy has become the first treatment option for diseases such as melanoma and lung cancer in some countries. But its use for palliative care is uncommon.

“The intention to use immunotherapy should be curative even if it will not work for all patients,” said Christian Blank, a doctor and researcher from the Netherlands Cancer Institute who said he’s been using immunotherapy as a first option for patients with advanced melanoma, with good results. “I think investing 100,000 euros or dollars a year for palliative care is stupid. That I can do with dexamethasone [a steroid drug], or morphine.”

European and American doctors and scientists interviewed by Al Jazeera expressed interest in Xu’s model but also concerns that therapies that haven’t been proven effective through randomised clinical trials might harm or be used to take advantage of desperate patients.

Randomised clinical trials involve patients with the same disease being randomly assigned to a control group, which receives no intervention or a standard treatment, or to another group, which receives the new treatment. At Fuda, members of the control group have opted to not receive treatment, according to Niu. This does not meet the standard of a randomised clinical trial.

Without a randomised clinical study, a hospital can’t tell for sure whether its treatments have indeed been effective or if the patient just happened to have a slow advancing tumour, explained Tim Dudderidge, a urological surgeon who focuses on prostate and bladder cancer at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust in Britain.

“Otherwise, there’s a danger you may offer false hope, and the response changes are completely unrelated to the intervention,” he said.

Dudderidge uses cryosurgery for intermediate-risk prostate cancer or for cases where the disease has recurred after treatment, but it hasn’t spread outside of the pelvis. The doctor said he had not heard of cryoablation being used as palliative care for advanced-stage cancer patients, but if the practice yields positive results, he would be interested to learn more about it.

“If there’s an opportunity to do things differently, once they did it differently, rather than believing their own observations, they should scrutinise it in a scientific way to be useful for the international society,” he said.

![Xu Kecheng points to a poster describing one of Fuda Cancer Hospital's clinical trials [Simina Mistreanu/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/604cabfd3a784ccba5479577a1fa318a_18.jpeg)

As China’s economy and geopolitical prominence have grown in recent years, its role in the international medical arena has also changed. The country has transitioned from being a destination for aid funds to becoming a partner in developing innovative health products, said Bernhard Schwartlander, the WHO China Representative.

The WHO estimates that by 2035 there will be 24 million new cancer cases around the world per year, up from about 14.1 million new cases in 2012. China registered 4.3 million new cancer cases in 2015, according to a report from the National Cancer Center in Beijing.

Institut Curie, one of Europe’s leading cancer institutes, is partnering in the construction of two new cancer centres in China.

One is being built in Changsha, Hunan province, as part of an “international medical city” with a total investment of 16bn yuan ($2.5bn). The other will be in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, and aims to be an “international medical brand“.

Pierre Bey, an adviser to the president of Institut Curie, who has brokered the partnerships in China, said the French institution’s role will be to bring expertise in areas such as multidisciplinary care, palliative care and research. China’s advantage – and its potential contribution to international medicine – is its capacity to conduct clinical trials faster owing to its large population, Bey said.

“What we have done in 30 years, China will do in 10 years only,” he added.

Regarding Fuda’s model, the French doctor said that for certain cancer patients, it’s important to offer less aggressive treatments, which will allow them to live as long as possible with fewer side-effects. But, he stressed, the hospital needs to evaluate the procedures and compare them with more standard treatments, such as chemotherapy.

“The vision of Institut Curie is everything is interesting in oncology, but it has to be scientifically evaluated, and I think this is the key,” he said.

All the treatments advertised at Fuda have been approved by the China Food and Drug Administration. As for combination therapies, guidance is generally issued by medical associations and the ministry of health, explained Fabio Scano, a disease control coordinator at the WHO Bejing office.

The CFDA has come under fire in recent years with accusations of corruption and lax oversight. The WHO, with financing from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is currently assisting the CFDA in a project to reform the agency, strengthen its regulatory capacity and align it with international standards.

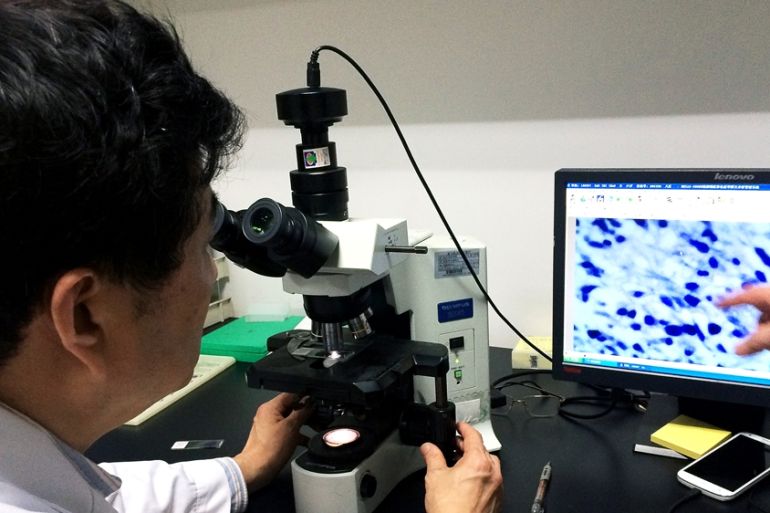

Fuda conducts clinical trials in labs on the hospital’s seventh floor. Here, the hallway walls are covered with posters detailing the results of various studies. In two, which looked at the use of stem cell vaccines for treating ovarian and lung cancer, the hospital has collaborated with the University of Michigan.

Wu Zihao, a colon and rectal surgeon at University of Missouri Health Care, said he believes that both Chinese and American physicians, in general, strive to treat and cure cancer, but in China “there might be a lack of standardised guidelines for treating cancer patients”.

Wu, who attended medical school at Sun Yat-Sen University of Medical Sciences in Guangzhou before moving to the US, said he would encourage Fuda to conduct a prospective, randomised control trial to examine the efficacy of its minimally invasive treatments and immunotherapy for patients with advanced-stage cancer.

That is not to say that using novel therapies or combinations on advanced-stage patients without randomised clinical trials is uncommon or necessarily unethical.

In the US, until a few years ago, many of the combination therapies for cancer were not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, explained Lichtenfeld, the deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society. The individual treatments were FDA-approved, but not the combinations, which were sometimes used in clinical trials.

These treatments were called “off-label”. They are less common today, Lichtenfeld said, because insurance companies have become stricter about the types of combination therapies they cover, so many of the treatments that used to be “off-label” are now FDA-approved.

But even today, a patient in the US who can afford to pay out of pocket for a therapy to be used in an uncommon way, and whose doctor agrees to the procedure, can go ahead and do it, Lichtenfeld said.

“The ethics are reasonably well-known: You should not do to a patient what you have not discussed with a patient freely and openly, and no patient should be treated who does not freely consent and understand the treatment they’re receiving,” Lichtenfeld explained. “And if a drug is not a standard drug for the disease, it should be offered to a patient as part of a clinical trial or at a minimum in a way that there is quality information obtained from that experience that can be shared to the benefit of everyone.”

![Xu Kecheng talks to PhD students who work as researchers in Fuda Cancer Hospital's laboratories [Simina Mistreanu/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/69c90ecd69274b998f4e371c4601cc60_18.jpeg)

‘Weapons and knives against cancer’

Care for the terminally ill is changing, and being debated, across the globe. In the case of cancer, doctors at first treat to cure, but they also treat for comfort.

“It’s very much part of our tradition in cancer care to treat patients with chemotherapy or other cancer treatments to improve their comfort, although we won’t provide a cure,” said Lichtenfeld. “If we were only treating for cure, for many patients we would stop at surgery.”

For patients and their families, it’s often hard to decide when to stop so-called “active treatments” – those which are meant to cure.

Erik Fromme, a palliative care doctor who specialises in cancer at Oregon Health and Science University in the US, said he discusses with his patients their understanding of their disease, their priorities, their fears, their hopes, and helps them make the decision that will best suit them.

“I think people continue to do treatments as long as the benefits outweigh the burdens as they understand it,” Fromme explained. “But there are people who find benefit to just being in treatment, whether the treatment is working or not.”

People want another shot at life, and they will travel the world to get it. Part of it has to do with the tendency to describe cancer as a “fight”. This comes naturally, Fromme said, when the “weapons” we use against it resemble poison and knives.

The flip side of that interpretation is that stopping treatment is likened to being defeated.

Emotional support

After her second visit to Fuda, Pietroiu returned to Romania. Her friends had launched a campaign to raise money for further treatment in Guangzhou. But she never returned to China.

In Romania, she stopped treatment, her husband said, not because she wanted to but because doctors there told her there was nothing they could do for her. She died on October 9, 2015, surrounded by family.

Bogdan considers cancer treatments to be a bit like a lottery – you try your best, but you have no guarantees.

“My only regret is that Raluca is not here any more,” he said. “The rest doesn’t matter. All the time, money and effort I think were well invested. If Raluca were here, it would have been wonderful.”

![Raluca Pietroiu and her cat, Mauriss [Photo Courtesy of Bogdan Pietroiu]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/5ee926c51232409095455432f21e1954_6.jpeg)