India’s Gujarat embroidery – a rich cultural mosaic

Living and Learning Design Centre in Bhuj painstakingly documents and helps teach more than 50 styles of embroidery.

Bhuj, India – The international spotlight was on this city in Gujarat state after the devastating 2001 earthquake that killed nearly 20,000 people and destroyed about 400,000 homes.

The simplicity of the residential structures today in Bhuj, capital of Kutch district, is a testimony to people knowing that everything hangs in the balance in the drought-prone region along seven major faultlines, making earthquakes an everyday possibility.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUK returns looted Ghana artefacts on loan after 150 years

Fire engulfs iconic stock exchange building in Denmark’s Copenhagen

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

Relying on external help to alleviate the distress of years of drought, the people of the region are no strangers to helping visitors. But little did Chanda Shroff, who came to Dhaneti in Kutch in 1969 to help in the free kitchen run by the Ramakrishna Ashram, know that she was on the cusp of creating history.

Chanda was enamoured by the embroidery work done by the women here. Her keen observation led to the understanding that the stitches used, the patterns and motifs, were community-specific and hence identity markers that often adorned the garments, which again were distinctive to each group.

Every form of embroidery was rooted in a culture that was assimilated by the various communities through their migratory patterns and influences of the regions they settled in.

Encouraging these women to explore commercialising their skills was a hard sell considering the communities never viewed embroidery as a skill, much less a means of earning.

“In fact, it was seen as a sign of desperate times if one were to consider earning from embroidery. But Chanda was convincing,” explains Ami Shroff,

Chanda’s daughter and managing trustee of Shrujan Trust, who took over the reins after her death in August 2016.

![The museum has on record and display 50 different styles of embroidery representing 12 communities of Kutch [Photo Courtesy: The Shrujan Trust]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/4eaff525f8984e7089833baaf99670c4_18.jpeg)

Over the next 47 years, Chanda discovered and documented embroidery forms across communities. The Shrujan Trust, which she founded for this purpose, soon culminated into The Living and Learning Design Centre (LLDC), India’s first and only craft museum that opened its doors in January 2016.

50 different styles of embroidery

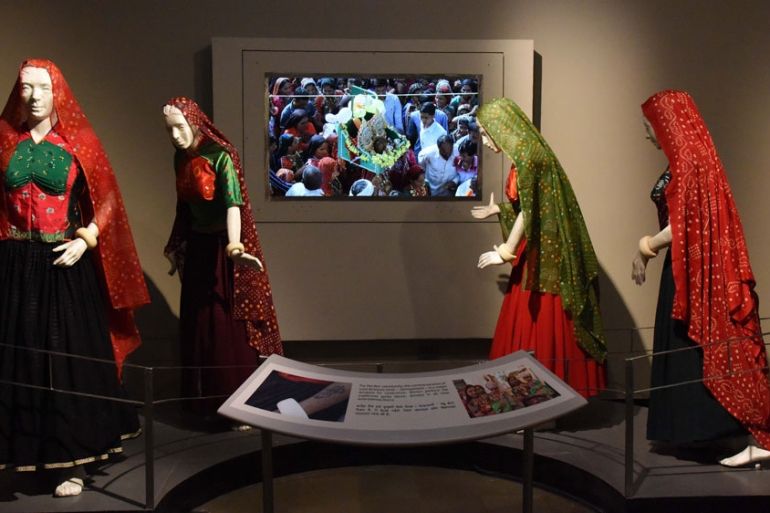

Today, the museum has on record and display 50 different styles of embroidery representing 12 communities of Kutch. Interestingly, none of the communities are native to the region, but are migrant populations that have come from Sindh, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia. And the process of discovery continues to yield something new even to this day.

The Living and Learning Design Centre has two parts to it – one has various embroidery styles documented and showcased in a world-class, climate-controlled display, complete with touch-based interactive screens that give details of every stitch and community.

The second is where artisans are provided a space to work on their skills. Infrastructure in the form of raw materials, power and even the teaching of business skills and marketing is provided.

For those who are homebound, embroidery kits for custom-placed orders are hand-delivered and picked up by the Shrujan team. This has worked well for women such as Bairajbaa Sujrajsing Sodha, 57, from the Sodha community and a Pakko Sodha embroidery artisan. She explains that she taught herself embroidery after the death of her father and began working to earn from it at the age of 22, when she was married but not allowed to leave home for work.

“I began working with Shrujan around 27 years ago. We heard that embroidery work was being commissioned in a village so I along with a few others headed there to get some for ourselves. And that is how we connected with Shrujan in Bhujodi village. I have embroidered many products for Shrujan and have supervised in the workshops conducted by them. Today I am the senior supervisor and teach girls in my village,” said Sodha.

In such ways, what began with 30 women, two communities and our village have now expanded to cover 120 villages and 4,000 women.

One of those is Mata Sariyaben, 67, from Dhaneti and an Ahir embroidery artisan who has been with Shrujan right from its inception. She moved up the ranks to become the Kendra (centre) head at Dhaneti where she teaches embroidery today.

“Like all girls, I began learning embroidery from my mother when I was 10 years old,” Sariyaben says. “I began with ghaghra [skirt] borders, torans [door decorations], bed covers and other household decor. The thought of helping other women who are confined by their caste and community rules is a major inspiration. Over the years I have trained a number of women through Shrujan who have become the primary earners of the family.”

International recognition

Designs are never a personal choice. A chief design maker, usually the elder in the community, would assign these. With printed garments coming in, the role of these designers diminished. Rather than let their knowledge die with them, Shrujan employed them and worked on passing their skill sets down to successive generations through training workshops. The project has brought out 550 master artisans in the process and this number is growing.

![Craft skills from the region have usually been passed down through generations [Ruth E Dsouza/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/dd07cd80c3024f1bbfeb088818a4324e_19.jpeg)

Fatmaben Musaabhai Mutwa, 48, from the village of Gorewali and a Mutwa embroidery artisan realised that in all her years, there were stitches that her mother and aunt knew that she did not.

“When I began working with Shrujan, like my mother did, I realised during the revival workshops they conducted that she and aunt knew stitches that even I hadn’t picked up yet. I learnt these from them and trained around 22 young girls in these stitches. It feels good to know that we are not leaving these skills behind in time,” she says.

“With the embroidery styles being passed down through the generations, there has never been names for any of the stitches or motifs,” explains Ami. “Painstaking discoveries, followed by in-depth conversations with the elderly women of each community has helped us put together a reference book for each style. Today, all of these and more have been documented at the LLDC.”

Craft skills from the region have usually been passed down through generations. The preservation and proliferation of indigenous embroidery forms of the region have brought the artisans international recognition and markets for their work.

“The idea in the long run,” Ami says, “is to expand the work done to dance, music, food and more.”

The First Shrujan Crafts Festival at LLDC, held in January of this year, was the first step towards bringing all these forms together comprehensively and there are several other plans afoot.

![The Living and Learning Design Centre, India's first and only craft museum, was inaugurated in 2016 [Photo Courtesy: The Shrujan Trust]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/c485cb840b0f4551994885aa9c1ee6cc_18.jpeg)