Reporting from Tiananmen Square in 1989: ‘I saw a lot I will never forget’

June 4 marks 30 years since the Chinese government violently ended weeks of pro-democracy protests in the heart of Beijing.

The student-led protests in Beijing had been going on for almost three weeks by the time I arrived in China on May 1, 1989.

In those days, there were far fewer international flights to and from the Chinese capital and so my journey was memorably circuitous. My itinerary was Hong Kong-Tokyo-Shanghai, and from there an 18-hour train journey to Beijing. Today, by the high-speed version, that same trip takes roughly four hours – as good a metaphor as any as to how China has come a long way very quickly.

I got to Beijing – or Peking as some broadcasters still called it – in time to cover a march of more than one million students on May 4. In the warm spring sunshine, the mood seemed festive rather than angry – that would come later.

Prominent among the student leaders was Wu’er Kaixi, a 21-year-old studying education administration at Beijing Normal University.

I remember thinking that he was both arrogant and charismatic, in equal measure. But millions of students hung on to his every word. Today, he remains adamant that the students were not seeking regime change when they began their mass occupation on Tiananmen Square, in the ceremonial heart of the capital

“We were having sit-ins. We were having mass hunger strikes. You do not bring down a government with a hunger strike!” he tells me during a lengthy interview in Taiwan’s capital, Taipei, where he now lives in exile.

“We did not want to bring down the Communist Party. We wanted to hold them accountable. We wanted political reform, freedom of speech and an end to corruption. We believed that the answer is democracy.”

The Chinese government responded by declaring martial law and ordering troops into the square to break up the pro-democracy protests. It has never been revealed how many died in the violent crackdown, but estimates by human rights groups and activists range from a few hundred to thousands.

In rare comments made on Sunday, China’s Defence Minister Wei Fenghe said the protests were “political turmoil that the central government needed to quell, which was the correct policy”.

He added: “Due to this, China has enjoyed stability, and if you visit China you can understand that part of history.”

‘Never expected live ammunition’

This time three decades ago, Wu’er gained international fame when his face appeared on the cover of Time magazine. In the years that followed, he has been a businessman, broadcaster and human rights campaigner. When it comes to China, he wants to remain relevant

I remind him of the night when state TV broadcast images of a hunger-striking Wu’er meeting Li Peng, the man who would later become China’s premier and who played a key role in the brutal crackdown. The setting was the Great Hall of the People and Wu’er was dressed in hospital pyjamas, wagging an admonishing finger in Li’s face.

It’s a scene unlikely to recur in my lifetime.

“A lot of people still remember the hospital gown, the gesture I put and probably I was a little agitated but I was on the fifth day of a hunger strike and there were hundreds outside doing the same,” Wu’er recalls.

He says they were typical students who believed their movement would bring change – not the carnage of June 4. After the declaration of martial law in late May, some students had begun to worry. But they never imagined their peaceful actions would end the way they did.

“We expected some bloodshed, to be hit by police batons, perhaps. That’s what we had expected. Live ammunition? No. Never,” Wu’er says.

June 4

I held a similar belief, and that was one of the reasons I and many others had left Beijing on May 28, convinced that the protest movement was petering out.

I returned early on the morning of June 4.

Along the old road from Beijing airport into the city – long since replaced by an eight-lane highway – was an almost unbroken line of tanks and troop carriers. My taxi wove its way through barricades of abandoned buses, a forlorn effort to try to impede the progress of the world’s biggest army.

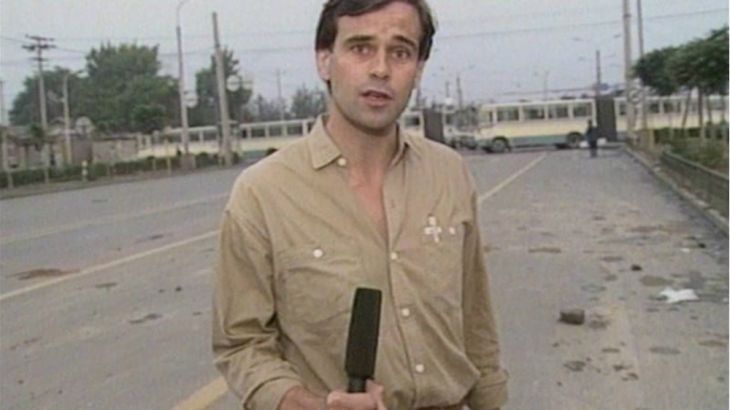

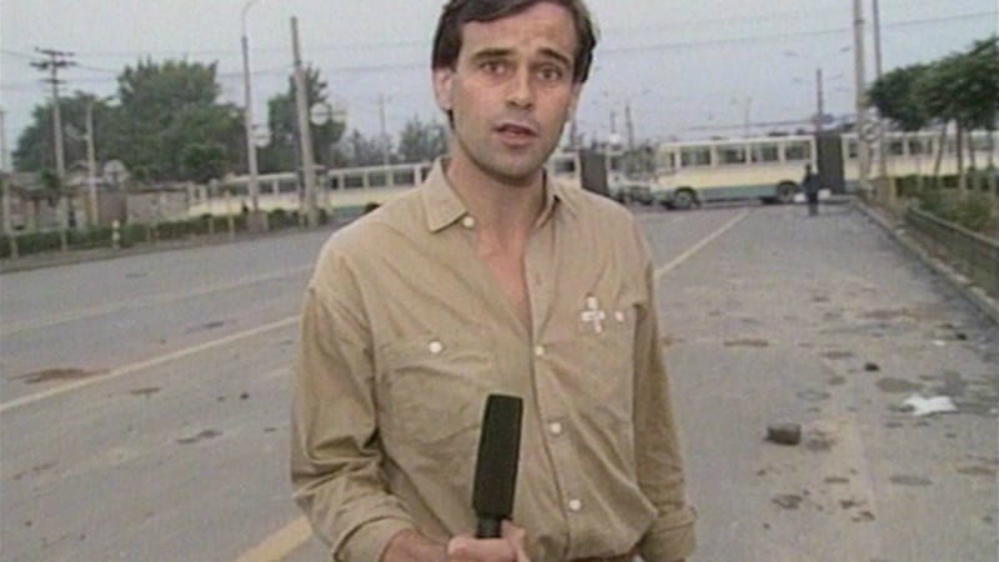

By mid-afternoon, under heavy grey skies, I and two colleagues were making our way along Chang’an Avenue, which ironically translates into English as the Avenue of Eternal Peace.

This is the thoroughfare that passes through the centre of Beijing and Tiananmen Square. Just a week earlier, thousands of protesters were still camping there. But the flags, bunting and a 10-metre-high statue of the Goddess of Democracy were now gone. In their place were thousands of soldiers, many of them forming a human barricade to block all access to the square, into which large troop-carrying helicopters were bringing additional reinforcements.

The army was in control. But these soldiers were not from the Beijing garrison, they from other provinces and had been told that an occupying force had taken over. Incredibly, a few men and women stood within a few metres of one army barricade hurling insults at the soldiers – gestures of defiance that were met with warning shots.

I saw a lot that day that I will never forget. A tank treading on two flattened bodies, a burned-out army personnel carrier and the charred corpse of a soldier inside.

The anger among many ordinary people was still palpable.

Fleeing China

On the other side of the city, Wu’er was in hospital being treated for heart palpitations. He’d been there several days earlier when he was summoned to meet Li Peng.

On the night of June 3, he knew something terrible had happened when bodies began to be wheeled in.

“The floor of the ER was covered by blood so the casualty must be very high. In the hospital, you can smell the blood. You can see the people are dying next to you.”

He says the nurses knew who he was and the danger he was now in. But the nurses and doctors did not betray him.

“They put me in the infectious disease ward. They believed it was a safer place. The PLA [People’s Liberation Army] soldiers wouldn’t go in there. But that place didn’t seem to be that safe afterwards so they moved me.”

Wu’er was eventually smuggled out of Beijing, making it to the southern city of Zhuhai from where he was spirited to Hong Kong by sympathisers.

Covering the crackdown

Back in Beijing, the job of being a foreign correspondent had become all but impossible. In once welcoming neighbourhoods – or hutongs – people no longer wanted to talk to us.

One night, a chilling report aired on the 7pm evening news. It showed the arrest of a man who had been wanted after talking to a TV news network from the United States.

The night before, the same news programme had shown a clip of him denouncing China’s government over the bloodshed – turn him in was the message.

Unable to broadcast our reports from China, we had to find people at the airport – mostly fleeing foreigners – willing to carry our cassettes to Hong Kong by hand. From there they could be beamed by satellite to anywhere in the world. Unfortunately, the Chinese authorities found a way to get a split of these feeds and download them into China. That’s how the authorities got their man – and many others like him.

‘Deploying fear’

Wu’er says he wants to return to China and stand trial on whatever charge the government wants to bring against him. But, of course, he doesn’t expect this to ever happen.

He also concedes that the events of 30 years ago are unlikely to be repeated. A vast security and surveillance network has seen to that.

“Let’s not forget the Communist Party has learned a great deal in the past 30 years in how to deploy fear,” he says.

“Fear is very, very present in China. In 1989, they established that with this massacre, the PLA soldiers. These days it’s no longer bloodbath. It’s more of patrolling police on the street to make sure they are very present and then throwing hundreds of thousand dissidents in prison.”