It is time to revolutionise how we talk about the weather

Over the past 50 years, the accuracy of cyclone forecasts has improved, but the way we communicate the risks has not.

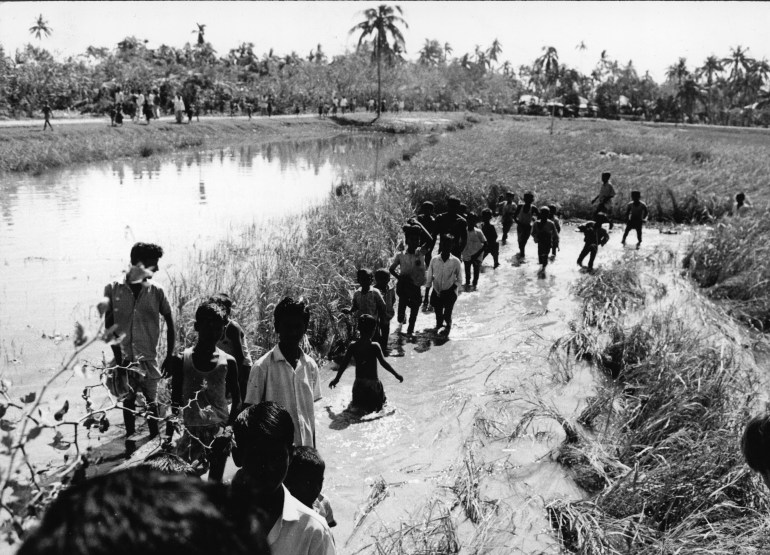

On November 12, the world marks the 50th anniversary of Cyclone Bhola and the associated storm surge that killed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people. It was the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded and one of the deadliest natural disasters.

The devastating effects of this disaster and the slow response of the government precipitated a series of events that eventually led to the Bangladesh war of independence, and to Bangladesh gaining independence from Pakistan in 1971.

But, 50 years on, for many countries, cyclones pose a greater danger than ever. One of those countries is Fiji.

On November 7, the prime minister of Fiji, Josaia Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama, became one of the first world leaders to congratulate Joe Biden on winning the United States presidential elections.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsYemen’s warring sides urged to prevent environmental disaster

Black Lives Matter protests spotlight environmental racism

Why are environmentalists being murdered?

He tweeted: “Congratulations, @JoeBiden. Together, we have a planet to save from a #ClimateEmergency and a global economy to build back better from #COVID19. Now, more than ever, we need the USA at the helm of these multilateral efforts (and back in the #ParisAgreement — ASAP!)”

Prime Minister Bainimarama says the “increasing ferocity of tropical cyclones due to climate change” now presents “the greatest ever threat to Fiji’s development”.

When Cyclone Winston hit Fiji on February 20, 2016, it was the most intense cyclone ever recorded in the southern hemisphere. It killed 44 people, destroyed or damaged 40,000 homes and significantly affected 350,000 people – roughly 40 percent of Fiji’s population. A state of emergency remained in place for 60 days and the total damage was estimated at $1.4bn.

Why are cyclones so dangerous?

Tropical cyclone-generated storm surges are among the world’s most deadly and destructive natural hazards and it is estimated they may have killed as many as 2.6 million people around the world over the last 200 years.

A storm surge is a coastal flood that is produced by a low-pressure system such as a cyclone.

Very low air pressure results in a higher-than-normal sea level near the cyclone centre. When this rise in water level under the cyclone is combined with a high tide or strong onshore winds, floodwaters can surge inland as the cyclone makes landfall.

While warmer oceans are increasing the intensity of cyclones, sea levels are also rising. In comparison with 2000, it is projected that sea levels will rise between 20-30 centimetres (7.8-11.8 inches) by 2050, leaving many coastal communities, especially those in small island nations, increasingly vulnerable to cyclone-generated storm surges.

But what if there was a way to better prepare for the dangers posed by cyclones?

Changing how we communicate

In the past 50 years, satellite technology, increasing computing power, and better prediction models have led to dramatic improvements in cyclone forecasting.

Today, our five-day forecasts are as accurate as a three-day forecast was just 20 years ago.

But, despite this revolution in the science of cyclone forecasting, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) believes the way we communicate the risks and effects of cyclones is still lagging behind, especially for small island developing states where these risks are increasing.

The WMO’s 2020 State of Climate Services report stresses the need for small island nations to adopt impact-based forecasting – a move away from “what the weather will be” towards “what the weather will do”.

For example, a traditional forecast might state that winds of 130 kilometres per hour (80.7 miles per hour) is expected, whereas an impact-based forecast would explain that wind is expected that can damage buildings and blow down trees, causing power outages.

For Fiji, such a change could be critical.

“The more we know and importantly, the more we can predict, the more intelligently we can act,” Prime Minister Bainimarama explains. “Our ability to interpret data that is accurate, timely and meaningful can literally save lives and be the difference-maker for Fiji’s sustainable development.”

Most small Island nations have already identified the need to develop more effective early warning systems for cyclones as a top priority. But the capacity for small island nations to communicate the effects and disseminate warnings is currently 30 percent lower than the global average (PDF), according to the WMO.

Following Cyclone Winston, the Fiji government found that the public understanding of the risks posed by a Category 5 cyclone was “inadequate”.

According to a post-disaster needs assessment report by the government of Fiji, “A number of coastal communities expected strong winds but were unprepared for the intensity of the storm surge, which contributed to poor decision making in relation to the location of evacuation centres and housing in coastal areas.”

Cyrille Honoré, the chief of the WMO’s Disaster Risk Reduction and Public Services Division, says the move towards impact-based forecasting for small island nations is also about improving the way different agencies can work together more effectively to protect vulnerable communities.

“The reason we are introducing impact-based forecasting in small Island nations is because it will help to save more lives and better protect assets, infrastructure and livelihoods. In the context of small island nations, these impacts may be significant enough to annihilate years of development efforts, so this is really a contribution to enhancing the resilience of these nations,” he says.

A new normal

Fifty years on from the devastation caused by Cyclone Bhola, today’s shift to impact-based forecasting must also be accompanied by greater efforts to enable vulnerable communities to respond appropriately to these warnings.

Researchers found that, although the Pakistani meteorological service had issued a warning for Cyclone Bhola, few coastal residents responded by moving to shelters. While only a small number understood the risks presented by the storm, for many there was simply no means of reaching adequate shelters in time.

Today, Fiji’s Prime Minister Bainimarama strongly believes the introduction of impact-based forecasting will enable his country to improve the way it prepares and responds to a new normal of “climate-fuelled, extreme weather patterns”.

“This work to improve cyclone forecasting is vital because it gives us a lifesaving window of opportunity to prepare for a storm’s arrival, allowing relevant authorities to make accurate and timely predictions for better-informed decisions. This allows for better management of related risks and supports clear messaging of critical information to the public,” he explains.

“It will also help manage and minimise risks and help build resilient communities, filled with families who know what to expect and how to effectively respond to tropical cyclones.”

Your environment round-up

1. What are you willing to change?: When Shell posted a climate poll on Twitter the response may not have been what they had hoped for.

2. Did environmental voters win the election for Biden?: How one non-partisan get-out-the-vote group targeted self-identified environmentalists who had never voted before – and how, in key battleground states, they turned out in numbers that surpassed the margin between Trump and Biden.

3. Greta getting the last laugh: As Donald Trump raged on Twitter, demanding “STOP THE COUNT!”, the teenage environmental activist used his own words against him.

4. Yemen’s ‘Manhattan of the Desert’: Can the centuries-old skyscrapers in the ancient city of Shibam be saved from rains and floods?