‘Growing up during the Bosnian War made me a journalist’

Al Jazeera journalist Alma Milisic was born months before the conflict began; one of the first words she learned was ‘siege’.

A personal essay by Al Jazeera journalist Alma Milisic, reflecting on 25 years since the Bosnian War ended:

One of the first words I learned as a child was “opsada” – Bosnian for siege.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHoliday Inn Sarajevo: In the Eye of the Siege

‘A camera doesn’t lie’: Documenting besieged Sarajevo

I was born in Sarajevo in July 1991, nine months before Bosnia’s war started.

Siege was the only thing people talked about, so it was no surprise that it was among the first words I spoke.

My parents, newlywed with two small children, packed their things and left their equally new home in hope of surviving.

Sarajevo had already been occupied for what would turn into the longest siege in the history of modern war, and the only option they had was to move around the city, from one municipality to another.

They settled in one of the villages on the Igman Mountain, just above Sarajevo.

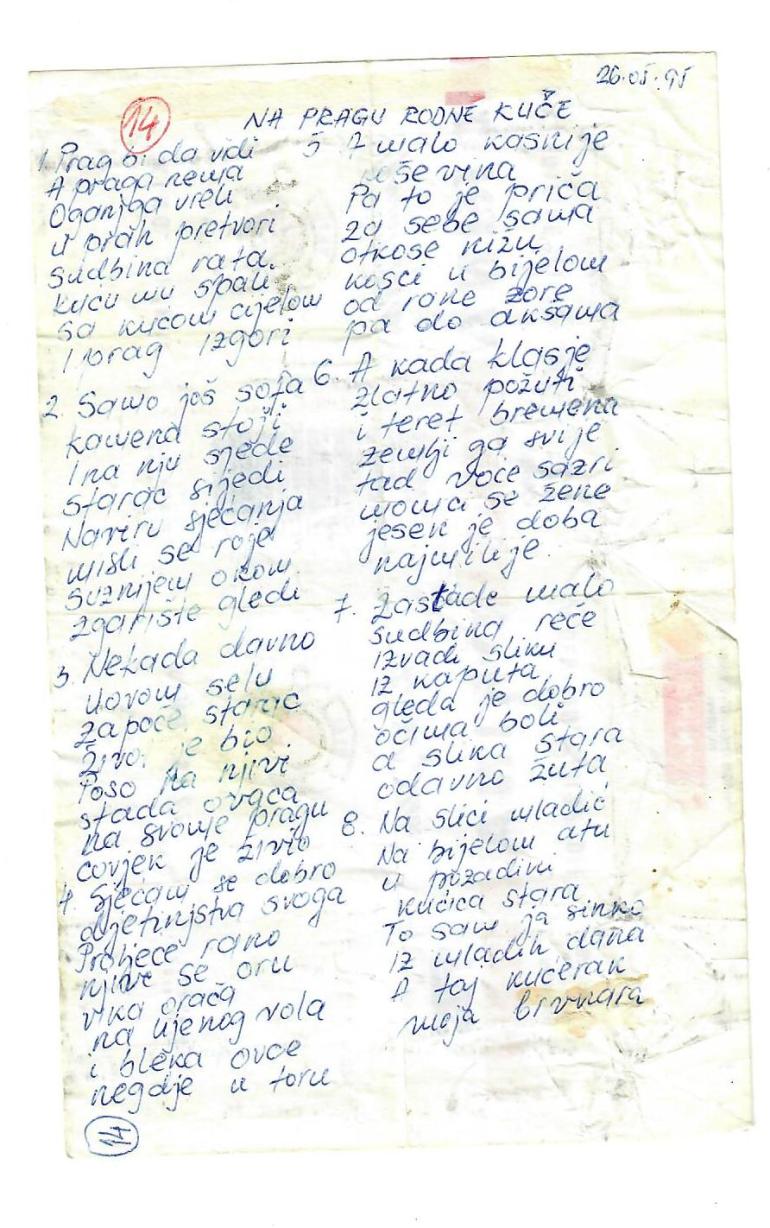

My father was an aspiring poet at the time. The war forced him to turn his poetry into a form of verse journalism, chronicling the events and reporting them on local radio.

Over the next four years, he wrote hundreds of reports, poems and observations from the field.

In 1993, after the offensive on Igman Mountain, my parents had no other option but to move back home.

My father was already serving in the military, leaving my mother, sister and I alone. It was no longer safe to live in our house, so we settled in with the neighbours, just across from ours.

Their home had a basement where several families, including ours, lived.

I had started to form my own memories of the war.

The windows at the neighbour’s house were shielded with sandbags, and the only ray of light we had was through the entrance door, which was mostly shut.

I would often crack it open when no one was looking, observing our house and imagining what it would feel like to live back in our own place.

In a war, you can be just a few yards away from your home, and still live in exile. Over the next couple of years, the yearning for our old house grew stronger.

My sister and I would spend hours listening to our mother’s stories of what our life would be like once we managed to move back in.

There was a serious lack of food and banknotes in Sarajevo at that time, but we had cigarettes in abundance: five cigarette packs for one kilogramme (2.2 pounds) of sugar, 20 for coffee.

On a few occasions, I would join my parents on their journey through the Sarajevo Tunnel, known as the “Tunnel of Hope” – the only way in and out of the city. They would carry a bag filled with cigarettes, hoping to exchange them for any type of food.

The passage was narrow, and my head kept bumping against the ceiling and my hands touched the walls, but I was in my father’s arms and nothing else mattered.

With every visit, my father would bring sweets, an apple, and a bundle of papers with his new writings.

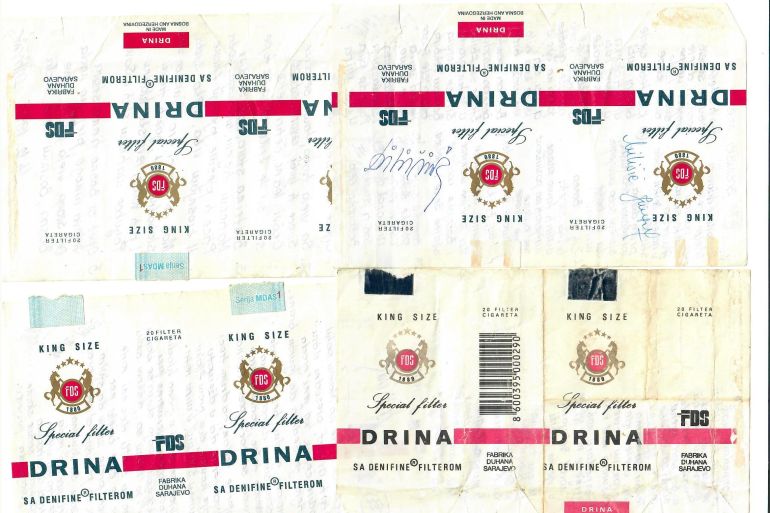

By 1995, paper in Bosnia had become extremely scarce.

My father would collect used cigarette packs and write on them.

On July 19 that same year, a few days after my fourth birthday, a grenade hit our home, taking with it the last hope of moving any time soon.

That year brought another important milestone – I joined my father for the first time on the radio. Not able to read, but having memorised most of his writings, I participated in his role as a witness over the next six months.

On December 14, 1995, with the official signing of the Dayton peace treaty, my father wrote his last report. Two years later, after the war ended, he published his first book.

I later told my father, “When I grow up, I will be a journalist.”

“I hope that you never have to report about war again,” he replied.