‘They were afraid of us’: The legacy of Britain’s Black Panthers

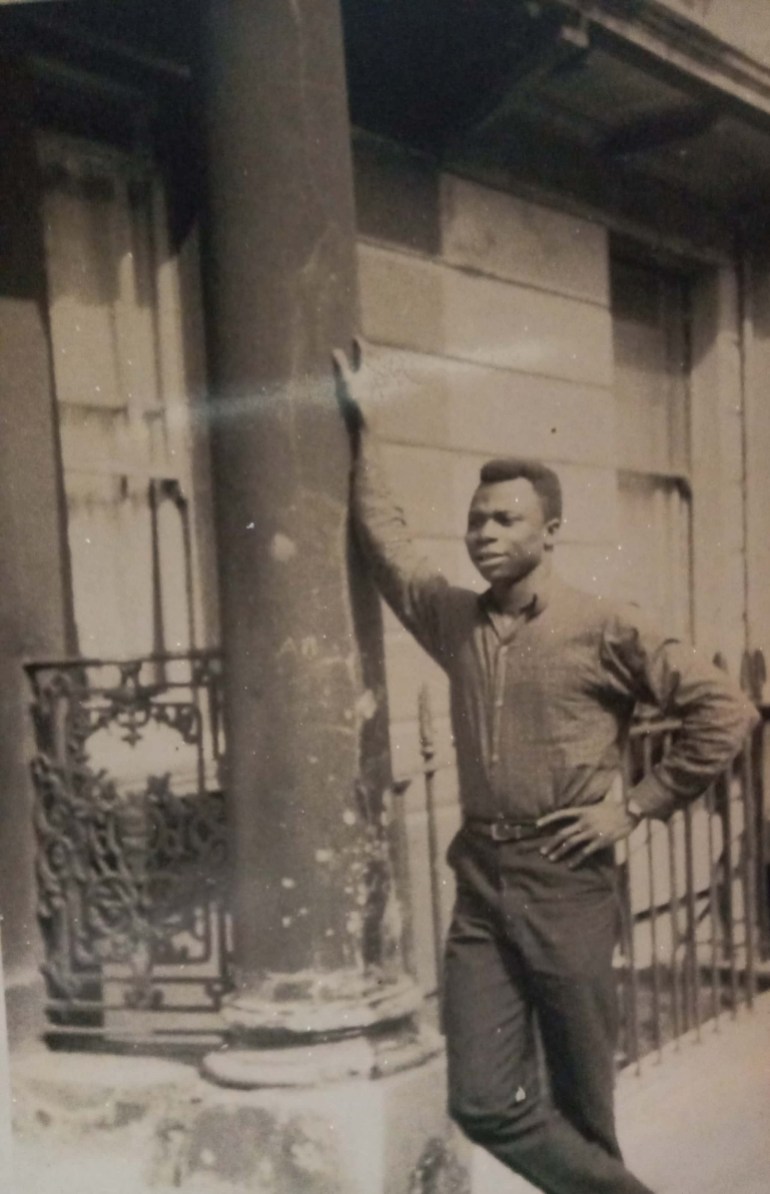

The 79-year-old Nigerian activist and founding member of the UK’s Black Panther Movement, Sam Sagay, looks back on a life of Black Power in Britain and Nigeria.

In March 1968, the streets surrounding Trafalgar Square in central London were crowded with an estimated 10,000 people demonstrating against the Vietnam War.

It was during these protests that Sam Arugha Sagay, a Nigerian student, and other anti-war activists stormed into the South African embassy to confront “the white power structure” of the Apartheid regime, which they saw as facilitating racism and war around the world.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFive Black British figures history forgets

Black autonomy and lessons from the Black Power struggle

The danger of depoliticising Black Power activism

Back on the streets, headlining activist and actress Vanessa Redgrave was leading the march to the police-blockaded American embassy in Grosvenor Square, where she famously delivered an anti-war petition addressed to the ambassador.

Despite the protests being mostly remembered for the violent clashes which ensued, they also embodied an era where the student, counterculture and Black Power movements united in opposition to the establishment. This was one of the many occasions on which Sagay, a founding member of the Black Panther movement in the United Kingdom, would take direct action against authority.

Feeling like an outsider

Coming to Britain in 1964, Sagay, who was born in Nigeria in 1941, could not have foreseen the political education and experience he would gain in the years to come. From his involvement in student politics to standing up at Speakers’ Corner at London’s Hyde Park Corner, and his role in establishing the British Black Panther movement, Sagay promoted Black Power ideology and argued for the need for revolutionary pan-Africanism.

Sagay was born to a family of seven children in Sapele, Delta State, where his father worked as a teacher and his mother tended to the family home. His primary and secondary school education was spent in his childhood town but, a year after finishing school, he moved to Ibadan in Oyo State where he was hired by the Federal Ministry of Labour to work in its western region headquarters in 1960.

Two years later, Sagay was sent to the Nigerian capital, Lagos, before eventually being transferred to work in London in 1964 when he was 23 years old.

There, Sagay first moved in with his friend, Tony Izelien, in Brixton, south London. He later rented a property in Victoria, central London, from a gentleman who, he says, “took a liking” to him, because the Nigerian city of Port Harcourt had been named after the landlord’s relative, Colonial Secretary Viscount Lewis Harcourt.

He attended Wandsworth College and the University of Westminster. While there, he became the office manager for the London Organisation for Student Community Action, before assuming the role of manager at the University of London Union on Malet Street near Tottenham Court Road.

Reflecting on his time at university in London, Sagay says he recalls feeling like an outsider and “living the life of a Black student in a white society”. Racism, as he remembers, was prevalent in all aspects of British society, although within the university space it was “more subtle” and harder to articulate.

Sagay says he found the nature of British racism to be somewhat insidious. “You know the British people [can be] very subtle. They operate in a very subtle manner so you would not even know the evils in their mind,” he says.

From 1965, Sagay began attending Hyde Park’s Speakers’ Corner where he was introduced to a host of rebels such as Nigerian playwright, Obi Egbuna, Dominican activist Eddie LeCointe, Guyanese orator Roy Sawh and the infamous Trinidadian revolutionary, Michael X.

Speaker’s Corner quickly became a platform for Sagay’s political beliefs as he joined his comrades in speaking about Black nationalism and pan-Africanism. His newfound friends were an eclectic mix of radical figures who fought against racism with differing approaches and skill-sets.

For someone who witnessed and participated in some of history’s biggest social movements for change, Sagay is today a remarkably humble and unassuming man. Speaking at his home in Benin City in Nigeria’s Edo State, his eyes light up as he recounts stories about his old friends. He recalls Sawh as being a “good speaker” with Trotskyite politics. X, on the other hand, was a well-established activist “but not of high intellectual abilities”.

During the late 1960s, X had become a controversial figure within Black circles due to his pimping of prostituted women and other “hustling” activities. These ranged from conning local residents to financially exploiting white liberals, like John Lennon, to secure funding for community projects.

X was also shamed for his working relationship with exploitative landlord Peter Rachman. Notorious for renting dilapidated properties to West London’s Black community, the “slum landlord” charged extortionate rents and used Black rent collectors, such as X, to intimidate tenants.

Despite the controversy surrounding X’s position in Black society, Sagay says, “He had some die-hard supporters in Notting Hill. Michael was more or less a doyen in the area. There’s no doubting that he was conscious and believed in Black liberation.” However, when it came to “intellectual grasp”, Sagay says X fell short.

Black Power

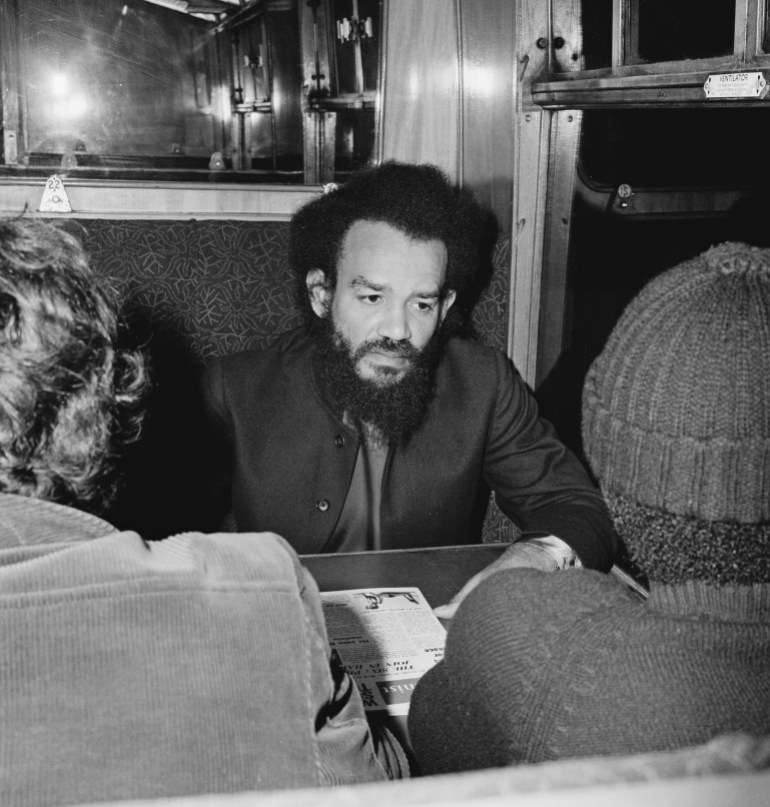

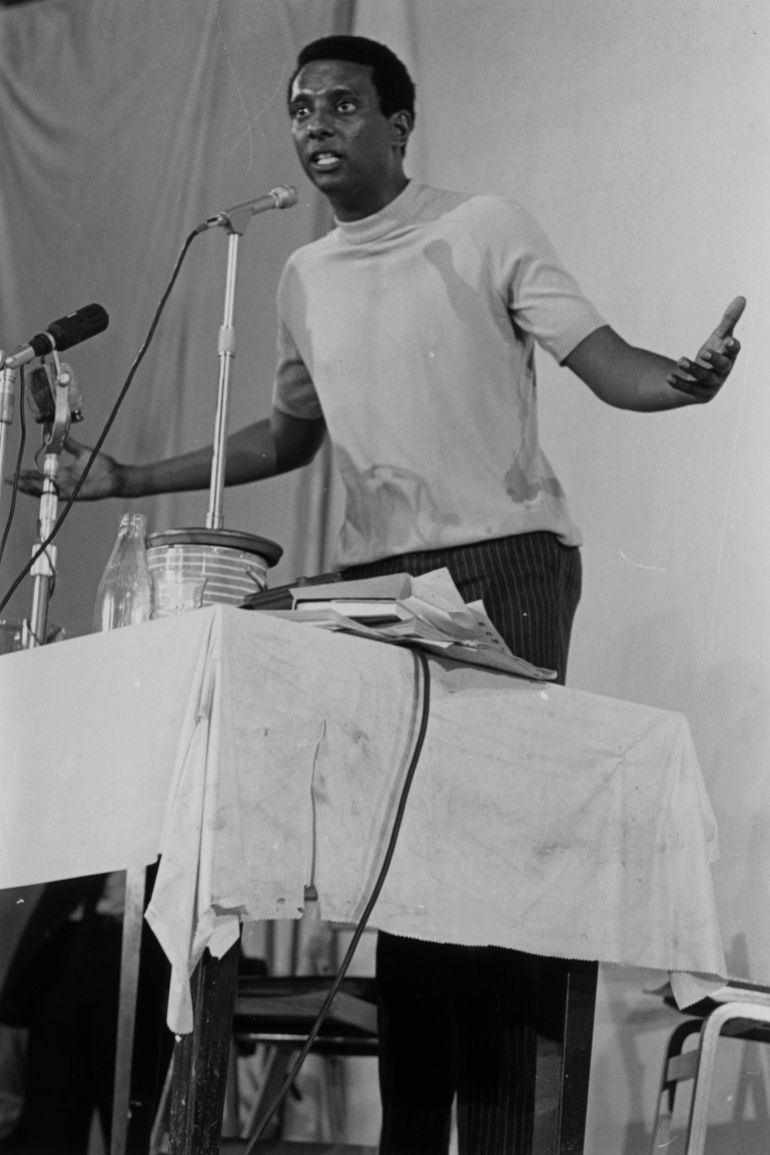

In July 1967, with the political turmoil of the Vietnam War raging in the background, a radical congress was convened at the Camden Roundhouse in north London, a popular haunt at the time during the 1960s countercultural scene. The event, titled the “Dialectics of Liberation”, was a meeting of radical academics and activists such as Herbert Marcuse, Allen Ginsberg and Joseph Berke. The headlining speaker of this congress was the African American activist, Stokely Carmichael.

There, Carmichael urged Black Britons to take anti-racist action and called for the creation of militant Black Power in the UK which could serve as an effective opposition to the racist politics of the white British establishment. Sagay recalls Carmichael “articulating our feelings, [both] in Britain [and] in America”. The message was that “Black people were suffering the same thing” and Black Power was the only way forward.

Sagay and his activist comrades escorted Carmichael around London, entranced and energised by the American activist’s words. It was following this visit, Sagay says, that the British Black Power movement was truly crystallised. Anti-racist organisations such as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) and the Universal Coloured People’s Association (UCPA) had preceded the congress, but neither group had yet adopted Black Power ideology.

Black Power organisations, which emerged following the congress, adopted militant stances against capitalism, racism and colonialism. Unlike the groups which preceded them, Black Power organisations refused merely to act as parliamentary lobbyists, which they viewed as ineffective and, instead, formed grassroots movements with much more radical demands. These groups included the Black Liberation Front, Black Unity and Freedom Party, and the Racial Adjustment Action Society.

Just days after Stokely’s visit in the summer of 1967, Sagay’s friend, the Nigerian playwright, Obi Egbuna, was invited to the annual general meeting of the UCPA and elected chairman. It took just two months for the organisation to get on board with the new ideology and publish a manifesto titled “Black Power in Britain”, which stylistically matched the philosophies of Black radical groups in the US.

‘They were afraid of us’

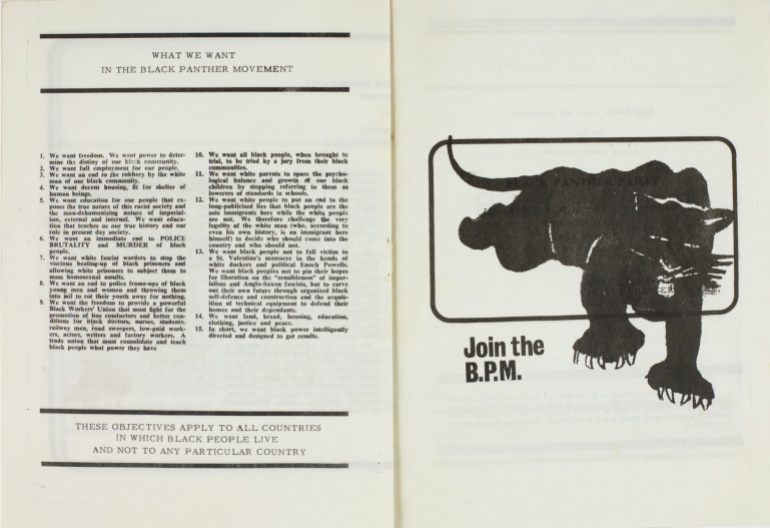

In April 1968, following a networking visit to the US, Egbuna turned down the chairmanship after being re-elected, and announced that he would be forming the Black Panther Movement (BPM). Sagay, who was still studying at university, became the secretary of the organisation and undertook duties such as managing its monthly magazine, Black Power Speaks.

The BPM organised demonstrations, produced Black Power literature and canvassed door-to-door in London’s Black communities such as Ladbroke Grove and Brixton. A major preoccupation, however, was police brutality in Britain, which largely resulted in Black men being racially profiled and targeted, beaten up or having drugs planted on them.

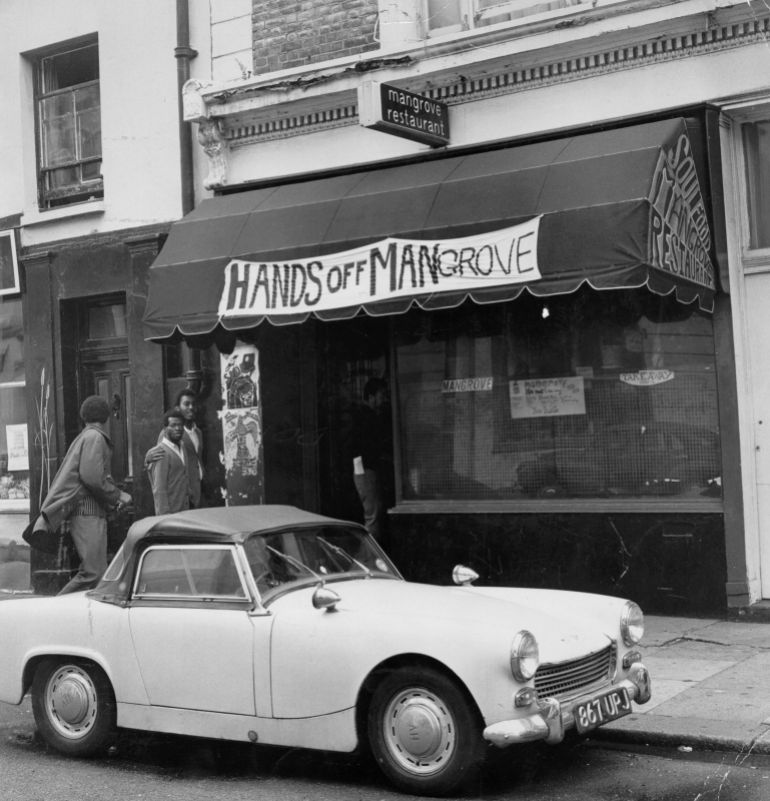

Sagay recalls police abuses as having been particularly bad for his Black peers living in West London’s Notting Hill. This abuse included racialised uses of stop-and-search, the framing of Black people for crimes and persistent harassment of Black establishments such as the Mangrove Restaurant, which served Caribbean food on All Saints Road. For many in the Black community, police racism was a daily occurrence.

One figure that Sagay and his comrades protested against was MP Enoch Powell, who courted controversy in April 1968 at the general meeting of the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre. His speech at the meeting became known as the “Rivers of Blood” speech, during which he strongly criticised rates of immigration to the UK, especially from New Commonwealth countries. Powell also stood against the proposed anti-discrimination legislation, the Race Relations Bill, which was passed that year and made it illegal to refuse housing, jobs or public services to anyone on the basis of colour, race or origins.

In its foundational years, the BPM was a male-dominated group, largely consisting of West Indians, Black Africans and South Asians who coalesced under the notion of “political blackness” – an umbrella term which united all Black people through their shared experience of racism.

“We fought the common problem of racism, [which was] especially incited by Enoch Powell – the devil,” Sagay says now. “We reacted to those kinds of things with our formation of the BPM, in line with what was happening in America.”

In July 1968, Egbuna, at that time still the chair of the recently formed BPM, was arrested for allegedly inciting murder of policemen in his pamphlet entitled “What to Do If Cops Lay Their Hands On A Black Man At The Speaker’s Corner”. Encouraging collective self-defence, the leaflet stated: “The moment the cops lay their hands on a Black brother, it is the duty of [the] Black crowd [to] surge forward like one big Black steam roller to catch up with the cop … till the brother is rescued, freed and made to flee at once.”

The document was alleged to have been handed over to the police by a printer-turned-informer. Following Egbuna’s arrest, there was an increase in incidents of police stop-and-search of Black activists at Speakers’ Corner which resulted in Sagay being accosted on two occasions. “On my way to Hyde Park Corner I was arrested [and] searched unnecessarily. They found nothing on me [but] that’s post-Egbuna’s provocative statement,” he says. He believes it was an impulsive response to the Black Panther Movement by the police: “They were afraid of us.”

Black Panthers are born

The BPM had branches in north, south and west London. While the exact numbers of those who joined remain unknown, former Panther and dub-poet Linton Kwesi Johnson has estimated that each branch was unlikely to have exceeded 100 members at their height. Referencing the BPM’s links to other Black groups in cities such as Nottingham, Bristol, and Manchester, Johnson remarks that “our presence was greater than our membership”.

While the mainstream media tended to portray the BPM as violent extremists, white countercultural magazines such as OZ, International Times and INK supported the Panthers’ anti-authoritarian commitments. Despite this, the BPM largely avoided external media, preferring to produce organisational newsletters such as the Black People’s News Service and later Freedom News.

The pinnacle of the Panthers’ strength was during the 1970 Mangrove Nine trial, which included prominent members of the BPM, such as Altheia Jones-Lecointe, Darcus Howe and Barbara Beese. Following a community demonstration against police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant in Ladbroke Grove, nine defendants were falsely charged with riot and affray.

During this trial, the nine captured public attention due to their appeal for an all-Black jury and their decision for three members to self-represent in court. Their strong defence strategy, the support of countercultural publications and the solidarity shown by the wider BPM network, resulted in the acquittal of their most serious charges and an unprecedented finding of racism within the Metropolitan police by the judge.

Reflecting on the alliances made between different radical movements during the 1960s and 70s, Sagay says that the Vietnam War was “the spark that brought everybody together”. He recalls three issues being most prevalent among his circle of activists: the war, struggles for student representation and racism. Despite being focused on his studies, Sagay says: “I wasn’t a dormant student, I was an activist.”

Sagay remembers there being a distinction between Africans within the Black Power movement and West Indians. He says that the former had come to Britain to study, with a clear goal to return to their home countries, while the West Indian community had largely settled in Britain. Consequently, he views this distinction as having led West Indians to take up the racial struggle in the UK with greater vehemence.

“Our political orientation was towards our countries, especially Nigeria, one of the biggest Black nations,” he says. “We were ready to change things there.”

A mission to ‘bring down capitalism’

Reflecting on his youthful radicalism, Sagay laughs as he reminisces about his early mission to “bring down capitalism” and eliminate racism. “That was our mental attitude at the time, but actually our political orientation moved towards our [home] country.” Ultimately, Black students like him became more concerned with the politics of the African continent.

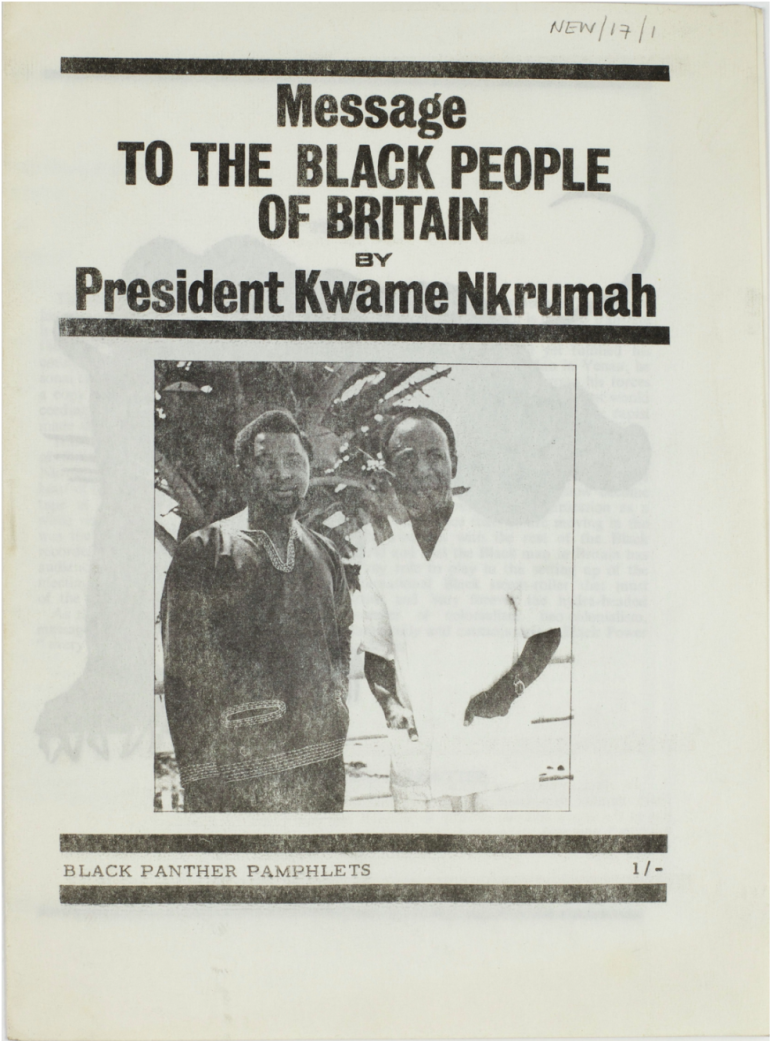

Black intellectuals such as Marcus Garvey, Edward Blyden and WEB Du Bois greatly influenced Sagay’s generation of pan-African activists. While the BPM sought inspiration from the American Black Power leaders, the Africans among the group were particularly drawn to the revolutionary pan-African ideas of Nkrumah and Touré. Sagay recognises the intellectual elitism of the BPM in its foundational years.

It was during his sojourn in Britain, lasting until 1972, that Sagay passionately engaged with former Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah’s pan-African politics. Following the Ghanaian military coup d’état in February 1966, Nkrumah had been living in exile in Guinea, at the invitation of Guinea President Sékou Touré. Despite being exiled, Nkrumah developed a Pan-Africanist network in Britain through his patronage of the BPM, his writings in Black radical newspapers and sponsorship of young African revolutionaries.

Sagay, along with a group of youths sponsored by Nkrumah, was sent around Europe and the USSR for “political training”, a subject which Sagay is reluctant to speak in detail about today. The alleged goal: to reinstate Nkrumah to power in Ghana and enforce pan-Africanism on the African continent. They were considered the “field soldiers for Nkrumah”, but in 1972, Sagay notes: “The old man died before realising his dream.”

Homecoming

The pressures of being a student and engaging in political activism took its toll on Sagay and some of his colleagues.

“We were all students, so we had to [ensure we could] continue with our studies,” he says. “It’s no use wasting our time in Britain, its better go back home and deal with our own problems.”

Sagay withdrew from the BPM in 1970 to focus on his studies, and two years later he moved back to Nigeria, feeling that it was “better to go back home and deal with the problem [there than stay] in Britain”.

On his return to Nigeria in 1972, Sagay’s political engagement continued when he joined Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN), which he deemed the most progressive party at the time.

UPN was a far cry from the Black Panther politics Sagay had engaged with in Britain, but he recognises the complexities involved in trying to instil Black Power ideologies in his home country. The country was just “too big and too diverse”.

“You see, [UPN had] a situation where we were trying to position ourselves into realising our dreams as it were – the dreams of the Black ideology – but with Nigeria being a very big and diverse country our efforts never materialised,” he says. “Within the states we controlled – Lagos, Ogun, Oyo, Ondo and Bendel – we did our best to make sure that the Black identity was properly established.”

Despite UPN losing out on a federal seat, it won the Bendel State governorship election in 1979 with Ambrose Ali as the party candidate. Sagay subsequently served as Ali’s campaign manager and chief of staff for three years until February 1982, when, Sagay says, he was “sacked for opposing the government on several issues of tribalism and corruption”. This followed Ali appointing his inexperienced uncle as a secretary, unfairly awarding government contracts and “dishonouring promises made during [the] campaign”.

“We fought against Ali’s second term as governorship candidate for the party, but he bought his way to victory,” says Sagay. Reflecting on his own move to the National Party of Nigeria (NPN), Sagay recalls that some members of UPN “moved to the opposition party”, led at the time by the progressive candidate, Samuel Ogbemudia, who succeeded Ali as Bendel State governor in October 1983.

‘A pale reflection of the white man’

When it comes to African politics today, Sagay argues that at the root of the continent’s problems is the “cultural deviation from traditional African culture” because of colonialism. He points out that the West “de-culturalised” Africans and left Black “surrogates” in charge of the continent. “The Africans need to rediscover their own culture,” Sagay says. But he also says that once this traditional culture is embraced – it has yet to be so – it must be revolutionised to suit the context of today.

“Africans have a very serious problem arising from the fact that they have been de-culturalised. Today the African [leader] is a pale reflection of the white man,” he says. “That has been our problem and that’s the problem in all the African countries today. [Africans] have not rediscovered themselves. No matter what kind of leader we have, the fact that he has lost his cultural background means that he has to be a surrogate.”

This cultural restoration is what will enable the African nations to prosper, according to Sagay. “In as much as Western culture is dominant in [Nigeria], we can only progress [not] develop,” he says. “Because the foundations on which we are supposed to develop is [the] white man’s structure. All our orientation is to catch up with the white man – and we cannot because by the time we move two steps, the white man will have moved 10 steps ahead. So, we are in a position of [constantly] wanting to catch up.”

Using linguistics as an analogy for Africa’s structural problems, Sagay argues that Africans are “talking to the white man in his own language and you can never speak the language better than him, because you are a student. He who is a master is always the leader [and] he can always change the rules when he wants. By the time he feels you are getting too close to him, he changes the rules.”

Sagay would like to see a return to pre-colonial belief systems in Africa. He says: “Asian countries kept their language [and] religion. These two principal factors are absent in Africa. And if you look at the world map anywhere there is Christianity outside Europe there is poverty.”

For Sagay, Walter Rodney’s 1972 classic, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, remains a relevant and vital text. It argued that European governments strategically exploited Africa, during the 19th and 20th centuries, in order to develop the global north, to the detriment of Africa.

‘Mandela and Mbeki are not my heroes’

Sagay remains critical of the consecutive African leaders who have assumed office across the continent and complicitly worked within Western structures. He is particularly scathing about those African heroes who have been lauded by Westerners.

Speaking with a tone of anger and disappointment, Sagay says: “People glamorise [Nelson] Mandela, people glamorise [Thambo] Mbeki. Those to me are stooges. If they had allowed African revolutionaries from the jungle to take over government in South Africa [things would be different], but of course white people package [them] as great Africans. They use that publicity and sell them to us as heroes. They are not my heroes.”

“Without a revolution, we cannot move forward,” Sagay says. His vision for Africa is one based on the premise of pan-Africanism. In his assessment, Western colonialism facilitated and exacerbated notions of tribalism to prevent African unity and revolutionary action. The working class, Sagay states, must be the ones leading the charge, as opposed to the bourgeoisie or military.

At the time of our interview, Nigeria’s EndSARS movement had gained significant momentum, with the country’s youth taking to the streets to protest against police brutality and the government’s repression of citizens.

Sagay expresses his profound happiness and pride at the action being taken by Nigerian activists. “We should hail them, we should honour them,” he says. According to him, “This struggle is not going to end no matter what the establishment does. Consciousness [has] spread, and if you can sustain it for some time, you will see a change. It is my prayer that there will be a change.”

The non-hierarchical nature of the EndSARS movement feels more promising for Sagay. “Leadership at this stage is not best, [as governments] will compromise the leader,” he states. He explains how poverty among Nigerian youths makes them vulnerable to state manipulation or bribery. Leaders, he argues, “will in due course emerge” but at the moment “nobody wants an armchair leader”.

Despite being a dual citizen, Sagay has not been back to Britain since 1972 and states that “he has never thought” of returning. Instead, he has chosen to settle in Benin City, where he and his ex-wife raised their daughter, Gbone. Today, Sagay says that he mostly just enjoys spending time with his family and watching his three grandchildren grow up.

Now in his 80th year, Sagay remains hopeful that he will live to see true change for Black people in Africa and around the world. “I’m on my way out. I’ve done my bit, but I still want to see the results of my efforts.” Referencing the numerous books, he has written, Sagay contends that “even if people don’t accept it now, time will come. They will see the sensibility in what I have been saying.