‘Fascist storm troopers’: Racist police violence in 1940s America

In 1949, truncheon-wielding police officers descended on the racially integrated concert of singer Paul Robeson.

For four years, pundits, op-ed writers and intellectuals have tussled over whether the word fascist accurately describes the persona and politics of US President Donald Trump.

Some commentators on the left have refrained from using the term, worrying that it cleanses US history by casting the Trump years as exceptional, offering an alibi for, as Samuel Moyn puts it, “the coexistence of our democracy with long histories of killing, subjugation and terror”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRwanda genocide: ‘Frozen faces still haunt’ photojournalist, 30 years on

Underground tunnels found in Israel from Jewish revolt against Romans

Lost in Orientalism: Arab Christians and the war in Gaza

Among those histories, of course, are multiple forms of racist violence, including the kind that brought millions out to the streets earlier this summer, sparked by the brutal police execution of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

But the events of 71 years ago today in Peekskill, New York show that the word fascist has played a particular, vital role in Black activists’ struggle against racist police violence; remembering this usage can reconnect us with a radical history of activism often buried in conventional accounts of the civil rights movement.

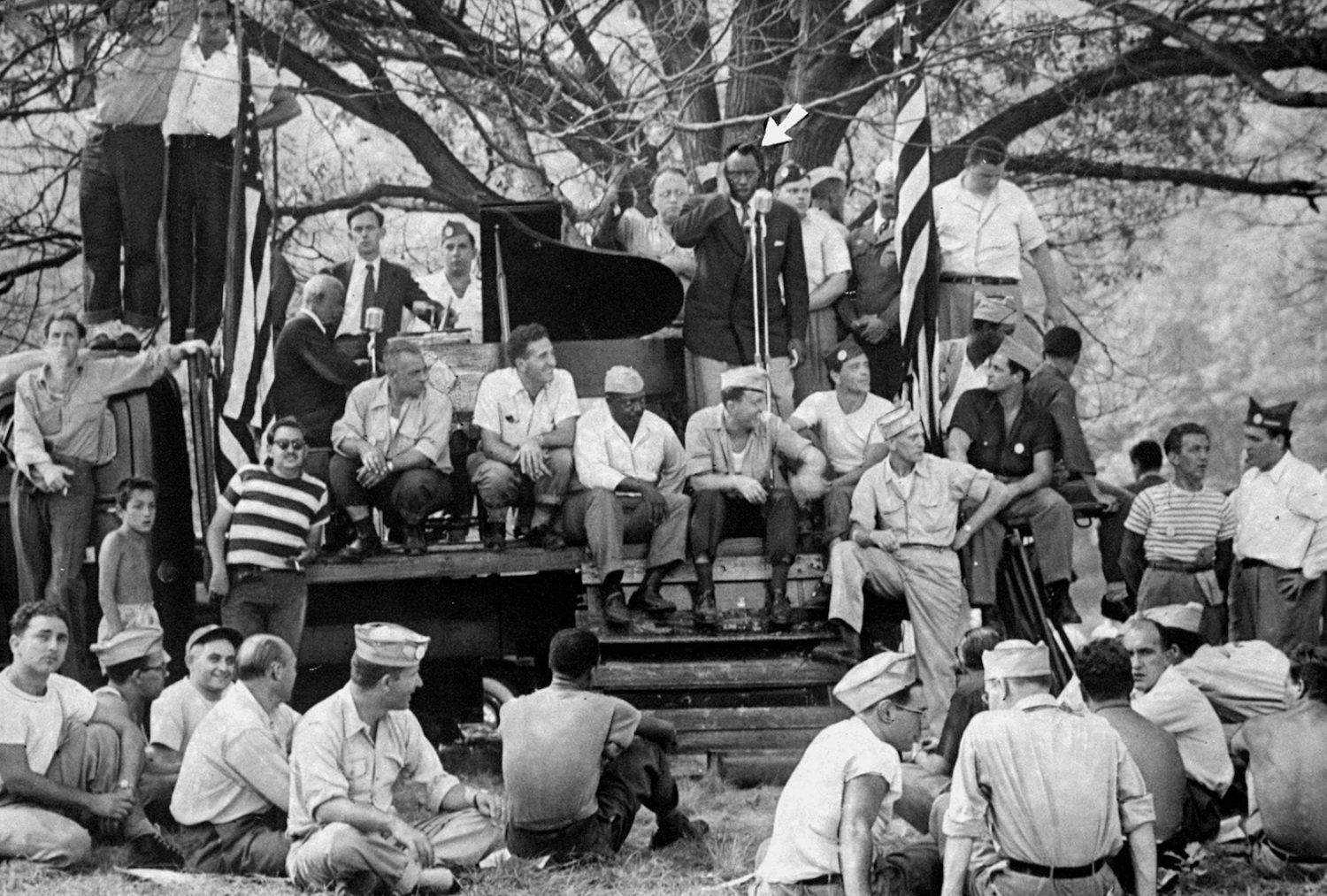

On the chaotic Sunday afternoon of September 4, 1949, truncheon-wielding police officers and stone-throwing rioters descended on cars belonging to the racially integrated audience of an outdoor performance by the singer and activist Paul Robeson.

Minutes after relaxing on blankets listening to Let My People Go and other songs from Robeson’s well-known repertoire, drivers and passengers girded themselves as rioters screamed at them: “Dirty Jews!” “Lynch Robeson!” and “Go back to Russia!”

Some exited their cars to fight back; others were dragged from them and beaten. The violence left at least 150 audience members with broken bones, lacerations, bruises, black eyes and other injuries. That no one died was a marvel. Concert attendee Woody Guthrie, riding back to New York City on a bus filled with shards of shattered window glass, confessed to his seat neighbour, “This is the worst I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen a lot.”

Speaking at a news conference in Harlem the following day, a still-shaken Robeson indicted the violence, singling out the police in particular as “fascist storm troopers”. Of course, it was only four years since the end of World War II, what many of Robeson’s leftist colleagues called the “war against fascism”.

The term had a concreteness and pungency that has, for many, declined over the decades. But raising the spectre of fascism was a rhetorical tactic that many in Robeson’s circle used to bring vehemence to state-sponsored racist violence in the form of police brutality, and to link that violence to more sensationalised practices associated with the South, like lynching.

In a speech at Harvard University a few weeks after the riots, Robeson’s friend and associate William Patterson, head of the radical, Black-led Civil Rights Congress, affirmed this focus, insisting that “the men who rule us are bent on fascism. They brought about the anti-Negro and Jew demonstrations at Peekskill just to see how the people would react to their big step to fascism.”

Why would a brief programme of traditional folk songs spark a brutal outburst of racism?

By 1949, Paul Robeson was a household name, but for many white and some Black Americans, his left-wing politics had begun to overshadow achievements in previous decades as an athlete (football at Rutgers University and in the young NFL), student (a bachelor of arts from Rutgers and a law degree from Columbia University), riveting actor (on stage and in movies), and charismatic singer.

In the 1930s, he devoted increasing time and energy to supporting the labour movement, anti-racist agitation, and anti-imperialist struggles around the world. He vocally supported the Loyalist (socialist) side in the Spanish Civil War, and paid a friendly visit to the Soviet Union, where he claimed to “feel like a human for the first time in my life”.

Robeson, like others drifting past the left-most reaches of the Democratic party, noted similarities between European fascist ideology and American capitalism. State-sponsored racism was one of the main points of alignment. As genocidal energy accelerated in Germany, the Black left, in particular, saw parallels not only in the enforcement of Southern Jim Crow policies but also in police brutality in Northern cities.

After the war, President Harry Truman and much of America assumed a warlike stance toward the nation’s recent allies, the Soviets. But Robeson and others on the left continued to praise the communist nation as an experiment in social and economic equality. The “Popular Front” alliance of liberals and radicals split, with liberal groups – including major civil rights groups such as the NAACP – taking up the anti-Red line and distancing themselves from groups and individuals who had not denounced communism.

In this political environment, Robeson’s radical politics made him unpopular with a wide swath of Americans. And, to be sure, the combination of his Blackness with his accomplishments, confidence, intelligence, grace and many talents – his status as what cultural critic Shana Redmond calls an “everything man” – meant he drew extra resentment and derision from many white Americans.

However, one remark was the most immediate trigger for the anger and hate that erupted into violence. In the spring of 1949, Robeson was touring Europe. By this time, war with the Soviets had begun to look inevitable. Speaking before the Paris Peace Congress, he questioned whether Black Americans would be willing to risk their lives in what would amount to a third world war, insisting that it was “unthinkable that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country which, in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind”. The right was predictably outraged. The New York Times editorialised that he should stick to singing. Leaders of major civil rights organisations declared their loyalty to the US.

In response, he doubled down, invoking the spectre of fascism: “We do not want to die in vain any more on foreign battlefields for Wall Street and the greedy supporters of domestic fascism.” Asked flat-out whether he would fight for the US, he stepped around the trap set for him: “I am an anti-fascist, and I would fight fascism whether it be the German, French or American species.”

Over the summer, the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed a series of Black community leaders to state their opposition to Robeson’s comments. The hearings culminated with the testimony of Jackie Robinson, who had integrated Major League Baseball two years earlier. Symbolically, Robinson’s appearance reassured white moderates that the nation was well on its way to achieving racial equality. It also reassured them that the fiery rhetoric emanating from figures like Robeson and William Patterson – including the use of the term fascism to describe the nation’s intentional treatment of African Americans – was mere extremism.

Later in life, Robinson said he regretted having appeared. But his testimony reflected the cautiousness of mainstream Black leadership, like the NAACP, toward Robeson and his more radical circles. Indeed, according to historian Marilynn S Johnson, mainstream organisations thought Black leftists were too focused on police violence, to the neglect of other issues.

Peekskill, New York, about 40 miles north of Manhattan, was, in the words of one of Robeson’s biographers, “a typically mainstream blue-collar place” – a phrase which in American parlance means, essentially, white and working class. Surrounding the town of about 17,000 were little summer vacation communities made up of “left-wing sympathisers … mostly Jewish”. That made Lakeland Acres picnic ground an appealing spot for Robeson’s management to arrange a concert for August 27.

When the booking was announced just two weeks before the performance, Peekskill’s local newspaper ran a series of red-baiting articles condemning “Robeson and his followers”. The concert organisers attempted to mount the show on the 27th, but people from the town blocked access to the location, as local police officers looked on without intervening. In a preview of what was to come, rocks and epithets were hurled at arriving concertgoers. Riding in a car with friends, Robeson made it as far as the edge of the ground, but when his fellow passengers saw what was happening, they pushed him to the floor and drove off, despite his protests.

In the days following the sabotaged concert, Robeson expressed his anger, targeting the police in particular, whose support of the attackers he labelled “a preview of American storm troopers in action”. The concert would go on, he said, on the following Sunday of September 4. Persistence in the face of violence and threats of more violence, he said, could mark “a real turn in the anti-fascist struggle”.

September 4 would prove the hurricane to August 27’s summer thunderstorm. The night before the performance, two effigies of Robeson were burned near the concert grounds. Concertgoers arrived to shouts of “We’ll kill you!” from hostile protesters, a solid 8,000 strong. Anti-Black and anti-Semitic invective reverberated all over. Some attendees may have naively felt more secure when they noticed a state police command post, four ambulances and a helicopter circling in the sky. Robeson performed ringed by union members scanning the crowd and the environs; some noted men with rifles in trees and on hills surrounding the concert grounds. Still, the singer completed his set.

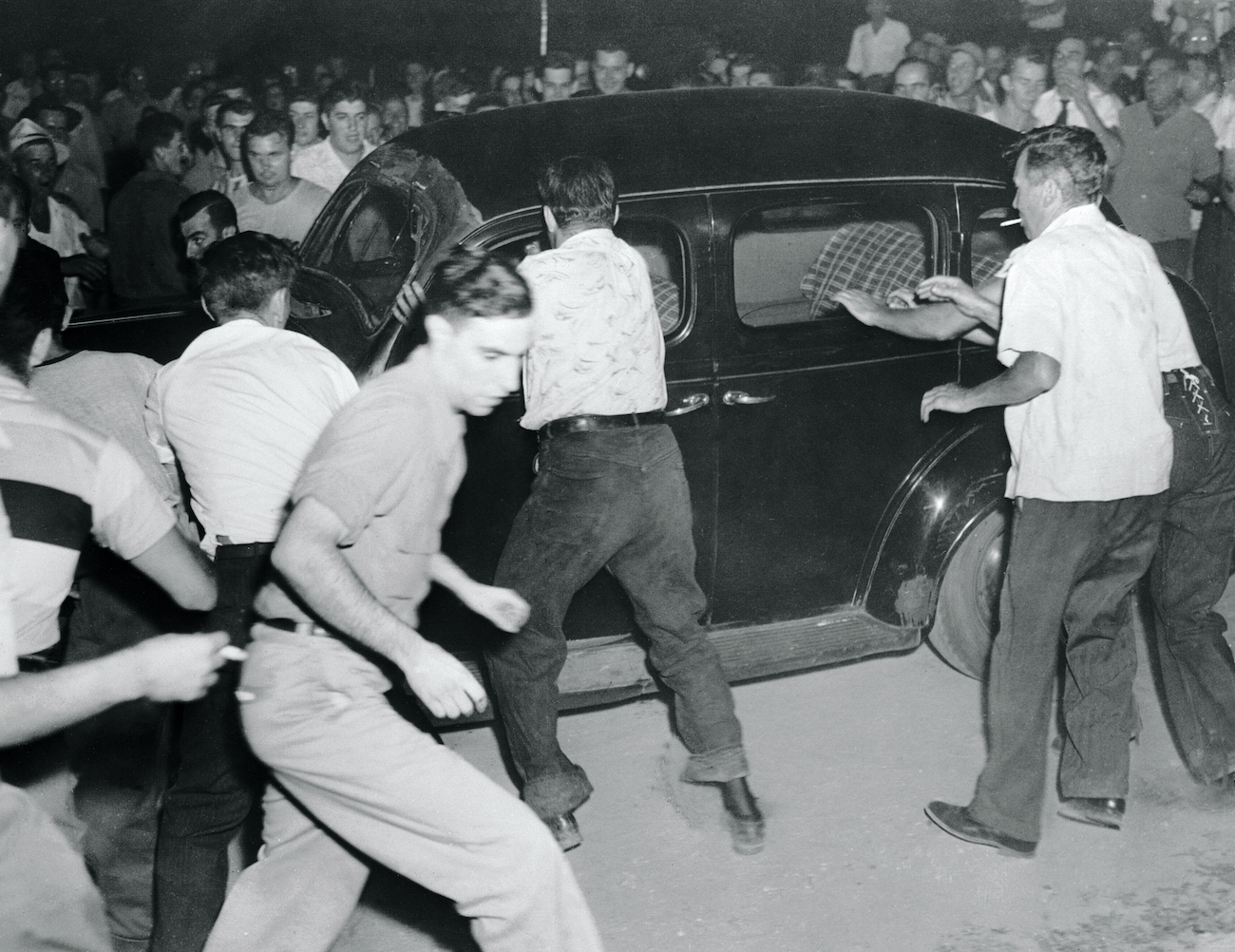

The brutality began afterwards and this time it was well-choreographed. Police directed exiting cars to a single road that led away from the grounds, a deliberate diversion that sent the audience members’ vehicles between townspeople waiting on each side of the thoroughfare, armed with rocks, bottles, and in some cases, knives.

Objects flew, shattering car windows. Some drivers and passengers were forcibly dragged from their cars and assaulted. They yelled “Give us Robeson! We’ll string that big n****r up!” “Dirty n****r lovers!” “Jew-k****!” and dozens of other racist and anti-Semitic jeers, some captured on tape by a CBS radio crew.

Witnesses reported dozens of police – state and local – taking part in the attack; images from the scene show them bringing down batons on a Black man. Many injuries required hospitalisation; in some cases, rioters got in their own cars and followed fleeing audience members, attempting to prevent them from reaching area hospitals. Somehow, no one died.

After the riot, New York Governor Thomas Dewey expressed his support … for the police. Although the violence was unfortunate, he said, “communist groups obviously did provoke this incident”. Robeson, in contrast, slammed the state police as “fascist storm troopers who will knock down and club anyone who disagrees with them”.

But outside of some corners of the Black press and labour newspapers, vocal support was tough to find. According to a grand jury convened in October, “Communism … and communism alone” lay behind the events; racism and anti-Semitism were not mentioned. Even A Philip Randolph, the civil rights leader who in 1963 would organise the March on Washington, blamed Robeson for exploiting the incident and called it “not racial”.

Two years after the Peekskill riots, Robeson presented a petition to the United Nations under the title “We Charge Genocide”. The text, written by Patterson, argued that racist violence was not a primitive aberration, the atavistic behaviour of white yokels in the South, but an ongoing, nation-wide, state-enforced process of legal lynching: “Once the classic method of lynching was the rope. Now it is the policeman’s bullet. We submit that the evidence suggests that the killing of Negroes has become police policy in the United States and that police policy is the most practical expression of government policy.”

Genocide was not only the provenance of Nazi Germany. Identifying fascism in their home country allowed Robeson, Patterson and the other signatories to the petition, which included the families of victims of both police violence and lynching, to depict racism as both systematic and innately lethal – and global.

When Americans think of the beginning of the civil rights movement, they tend to think of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr, of young Southern Black people being beaten and hosed in the streets of Southern towns. But part of the reason we identify these indisputably brave, brilliant figures as the movement’s founders is the suppression of radical and communist-affiliated voices like Robeson’s, who used the word fascism to centre state-sponsored racist violence, evident across the nation, in the fight for racial justice.

By invoking it, Black leftists portrayed American racism not as a problem of southern monsters and as-yet-unawakened, innocent whites around the country. Instead, they presented it as a deliberate application of force – North, South and worldwide – to maintain the existing power structure. For them, Peekskill was a perfect example.