Living with Lupus: Learning to love and listen to my body

‘After I was run over by a truck, the strange symptoms that had always ebbed and flowed were finally diagnosed. But it would take time to unpack the years of damage, trauma and medical PTSD.’

I was 23 years old when my ex-boyfriend, under the influence of drugs and alcohol, ran me over with a truck travelling at around 45mph as I crossed a street one evening in Fort Lauderdale. I spent the next year of my life recovering from my injuries, and the next two decades making peace with the suffering it unleashed and learning to love my body again.

You see, being hit was my “trigger”, and I would soon learn how triggers are intimately tied to the onset of symptoms in people who are genetically predisposed to autoimmune diseases. For some, their trigger could be a pregnancy, a stressful event such as a divorce or death in the family, or a severe illness such as COVID. Simply put, a trigger is something that taxes the immune system to the point where it goes haywire. My trigger was 3,000 pounds of steel crashing into me. And I have been trying to outrun the aftermath ever since.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWoman, seeking loan, wheels corpse into Brazilian bank

UK set to ban tobacco sales for a ‘smoke-free’ generation. Will it work?

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

“You have Lupus. A disease that is going to cause you physical and emotional pain every single day of your life. There’s no cure by the way. Your previous life doesn’t exist any longer. So, suck it up, buttercup, and learn how to deal with it. Our time is up. Good luck,” is what my doctor should have told me at the moment of my diagnosis.

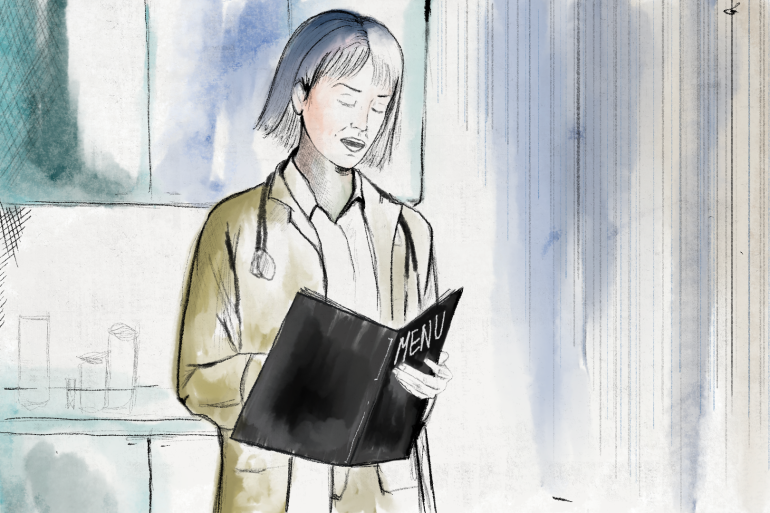

Label me a straight shooter – a quality you tend to pick up in a large, boisterous Italian family where speaking the truth, however uncomfortable it may be, is considered an act of love – but I believe I could have better prepared myself for the journey that is chronic illness if the rheumatologist who handed me the diagnosis almost two decades ago had been more forthcoming. Perhaps I could have pointed myself in the right direction in that pivotal moment, a healing path of finding solutions, rather than becoming a prisoner of confusion. Instead, her words were vague and emotionless, as though she were reading dinner options off a menu for the 100th time.

I have often wondered what the finality of a diagnosis feels like for a doctor and how it differs from a patient. Is it similar to a math equation, where symptoms + test results + physical exam = diagnosis, and once solved they immediately move on to the next problem (patient)? Because for patients, moving on seems impossible at that moment. We stand paralysed, feet cemented to the ground with a line of demarcation running between them – one side representing life before and the other, life after the diagnosis.

It is an overwhelming yet vindicating moment full of infinite unknowns.

About three months into my hospital recovery from being run over, the strange symptoms that had ebbed and flowed throughout most of my life exposed themselves. This time the pattern was different; they didn’t play hide and seek with one another, one peeking around the corner waiting for the other to hide again before showing its face. This time they banded together and made their presence known all at once. The fevers partnered with the pain, the rashes erupted with the mouth and nose sores, while the stroke and blood clot in my lung made a grand entrance. Add this to an already lacerated liver, broken ribs, head injury and multiple fractures from being hit, and it was clear my body had switched to full revolt mode.

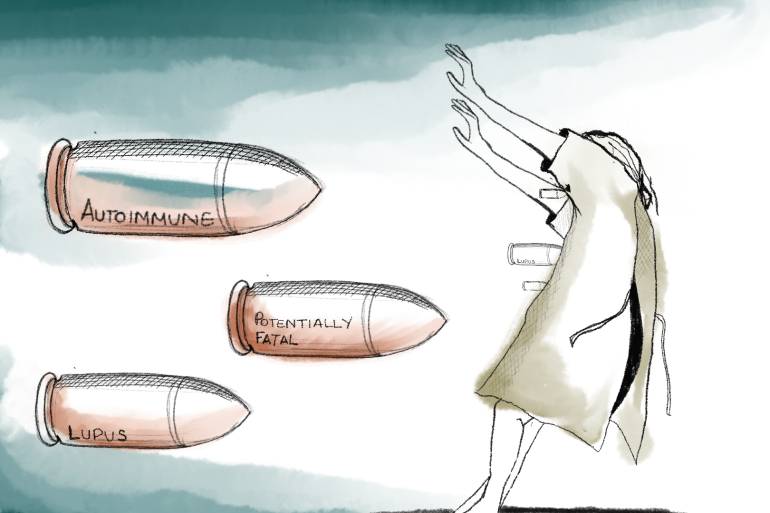

The two specialists who had been running endless tests on me entered my room. I stared at the rheumatologist’s perfectly shaped French bob, its blue-black colour illuminated by the fluorescent hospital lights. She reminded me of Veronica from the Archie comic books. Her hair swayed slightly from side to side as she spoke, the words “autoimmune condition”, “chronic”, and “potentially fatal” shooting from her mouth like bullets. Each terrifying one tore into me. And yet, like most moments of diagnosis for millions of people around the world, it was bittersweet.

This moment had been 23 years in the making. My body was now demanding that attention be paid to the problem it had been carrying for most of my life.

The truth is, my body hadn’t worked properly since the day I was born. It bewildered my young mom, who often reflects, “You were the most perfect little baby, I couldn’t even fathom that you would have so many health problems.” It started with an allergy to breast milk, and then subsequently every substitute – which back in the late 1970s was a pitiful list of options. Allergies turned into severe asthma and by the age of four, my first severe attack landed me in hospital for weeks. It would be the first of dozens upon dozens of hospital visits.

There were clear signs of autoimmune issues, but you didn’t hear about autoimmune disease often in the 1980s. There was no internet or e-book readers you could scour for information with the tap of a finger, no patient advocates sharing their stories and highlighting potentially obscure symptoms that could help an undiagnosed person begin travelling down the path to an answer. Instead, there were staggered trips to the doctor, when my single mother with no health insurance could afford it, only to be handed a stack of prescriptions and some version of a “she’s just a sickly child, delicate, and needs to rest” diagnosis.

And then hell disguised as paradise kicked my suffering into high gear.

When I was eight, we moved from Queens, New York to Fort Lauderdale so my grandparents could help take care of me. Florida had all the makings of a postcard: palm trees, sandy beaches, warm waters, orange groves and an abundance of sunshine. But, unbeknown to us, we had moved into an environment that would almost kill me.

Up to 70 percent of Lupus patients have disease activity triggered and worsened by the UV rays in sunlight. That year, I started showing classic signs of Lupus – severe reactions within minutes of sun exposure (continually brushed off as sun poisoning by physicians), mouth sores, constant fevers, severe fatigue, hair loss, sores on my scalp, and anaemia.

Going to school was like walking into a lion’s den. At lunch, I ate alone because others feared I was contagious and the school nurse often called my mom to pick me up as I had a fever and “shouldn’t be around other children”. The doctors, meanwhile, dismissed my symptoms – blaming my anaemia on a limited diet, my fatigue on the anaemia, and never digging any deeper as the medical system ultimately failed another person it was designed to help.

Lupus – a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that affects more than five million people worldwide, and for which there is no cure – was never mentioned. Despite the fact that a few of its most common symptoms include rashes, joint and muscle pain, fevers, sores, fatigue, blood issues (including anaemia), and sensitivity to the sun, it was never even considered as a possibility. The first time I heard the word Lupus was the moment I was diagnosed with it.

I often wonder how much suffering could have been avoided if my family physician had run simple blood tests instead of brushing my mom off for years. I think of all the stress she endured working two or three jobs in order to pay for my doctor appointments and roster of medication, only to get nowhere. And I remember the times, late at night, when she would cry in the bathroom, believing me and my brother couldn’t hear her.

For years, we were both perpetually exhausted, and could see no end in sight.

Sadly, this isn’t unusual for the one in five people who live with an autoimmune disease. It took 15 years for my diagnosis, but the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA) currently estimates it takes patients three or more years, and four or more physicians, to receive an accurate diagnosis. For Lupus, that time frame gets pushed to an average of six years.

The reason: autoimmune diseases are tricky.

There are more than 100 types of autoimmune disease according to the AARDA and the symptoms of each can overlap with the others. Lupus has been nicknamed “the great mimicker” because so many of its symptoms can be found in countless other diseases, leading a physician to rule out the most common possibilities first. If they aren’t well versed in the plethora of symptoms of autoimmune diseases, these possibilities may be overlooked – sometimes for years.

A while back, I met Ron Rocca, the president and CEO of Exagen Inc, who created a breakthrough testing system called AVISE to help Lupus patients get quickly and accurately diagnosed. When I asked what drove him to create this system, he answered, “Every patient deserves the dignity of a diagnosis.”

His words cut through me, because patients are often shown anything but dignity when they are suspended in that purgatory-like state of pre-diagnosis. There, where we are often alone, we are dismissed, misdiagnosed and judged because our outer appearance doesn’t match what society has decided a sick person should “look like”.

When the diagnosis does come, we rarely discuss the suffering that led up to it. But a diagnosis doesn’t magically wipe that slate of torment clean. It takes time to unpack the years of damage, trauma and medical PTSD; of being called “hypochondriacs” and “attention seekers”; of being ridiculed and not believed by those closest to us; of being brought to financial ruin as we’ve searched for answers; of losing our independence, our careers, our marriages, our confidence, our trust in our own ability to care for ourselves and, sometimes, our desire to keep on living because we cannot imagine enduring another day of this pain.

We are often a shell of ourselves by the time we are finally diagnosed. And then, completely unprepared for the journey we are about to embark on, we must navigate a new unknown.

If there is one thing I have learned, it is that chronic illness is not for the weak. It will push you to your limits – physically, emotionally and even spiritually.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. And that is where awareness and advocating for yourself come into play.

It is easy to see how common symptoms of Lupus – such as fatigue, fevers and muscle and joint pain, coupled with shortness of breath and painful breathing – can easily be mistaken for COVID-19, or a plethora of other illnesses, and why autoimmune diseases may not be at the forefront of a physician’s mind at the moment. But if you are experiencing symptoms, I recommend journaling. Most autoimmune symptoms wax and wane, so you may not connect your recent fatigue with your rash from a few months ago, or your intermittent chest or joint pain. You might brush off hair loss or exhaustion as stress from this past year and a half when our world changed. Write it all down – no matter how insignificant or erratic any symptom may seem.

Years ago, I pencilled symptoms on a paper calendar, whereas today I track them on my phone. Use technology to your advantage and take photos or videos of symptoms such as sores, bruises, rashes, tremors and swelling to show your physician because it is unlikely you will have them at the exact moment of your next appointment. In those first few terrifying months of COVID, when I lost my sight completely in one eye, it was photos and videos I took that helped a physician start me on the road to a diagnosis of optic neuritis due to Lupus. So log and capture everything.

Also, do your own research and speak up. If you have the financial means, seek out second or third opinions. If you cannot do this, advocate for yourself to your physician. Discuss the possibility of autoimmune, chronic and/or rare diseases and demand additional testing.

And, in the midst of all of this, pay close attention to your mental health. Because like water, the ramifications of illness will seep into every area of your life. Speaking with a neutral party such as a counsellor or therapist can help you navigate the flurry of emotions you are likely experiencing. If you are not insured or cannot afford a therapist, research universities in your area with graduate psychology programmes. They will have students completing therapy residencies who need to log hours with patients before they work in the field. These appointments are usually discounted and in some cases, free.

No matter what, don’t give up on yourself. You are not “crazy” or imagining things. Symptoms are burning red flags your body is waving to tell you that something isn’t right. Your body needs you to fight for answers because even though it may not feel like it, your body is fighting.

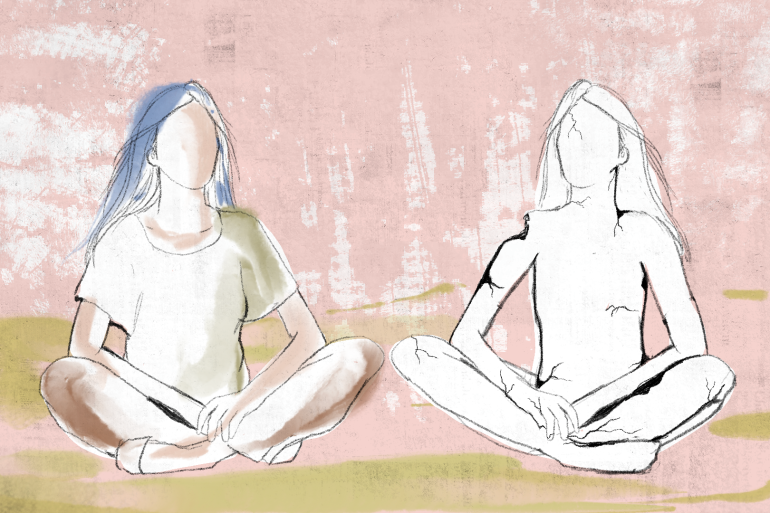

Years ago, I used to think my body had betrayed me. But today I understand that it suffered unimaginable pain and damage and yet it still kept fighting, crawling, clawing and gasping every step of the way. Now I pour love into it – through food, supplements, medication, therapy, prayer, rest and massage. Each day I make time to sit in silence and listen to what my body is trying to tell me. She has a lot to say. As I breathe in, I remind myself that she fought for me for 23 years despite being dismissed, ridiculed and turned away. Failing her again is not an option.