The ‘Skipping Sikh’: A story of faith, loss and racism

From the murder of his father to the racism he encountered when he first came to the UK, the moments that inspired the 74-year-old to skip the London Marathon.

It is a warm summer’s day and the sun is shining through the large windows into the small living room of our terraced house in West London. I am holding one end of my father’s turban – it is six metres long, bright orange, made from cotton. He tells me that tying it reminds him of his father, my grandfather.

As a boy he would sit cross-legged, hands together in prayer, in his village home in Punjab, India, watching his father tie his, in awe at how perfectly he did it.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMilkha Singh, India’s ‘Flying Sikh’, dies of COVID

Sikh community ‘traumatised’ after shooting at US FedEx facility

UK’s Sikh community prepares for second Vaisakhi under lockdown

“Every pleat would be in place and if it wasn’t, he would undo it and tie it again,” he tells me. There is a smile on his face as he remembers his father, but sadness in his voice.

My father refers to his turban as his crown and wears it with pride. Each day he takes about 20 minutes to tie it – never in a rush, his right arm wraps it pleat by pleat as he recites a prayer – “Waheguru” (“wonderful God”), he whispers.

At 74, he does not have much hair left, but he laughs recalling the long, thick hair of his youth. “Look at it now,” he smiles.

Almost finished, he takes the other end of the cloth, holds it between his teeth and tugs at the fabric to make it tighter. Then, with his right hand, he pats it down to make sure every pleat is just so.

With his turban tied, he disappears into the back room and returns a few seconds later with his skipping rope.

To many, my father – Rajinder Singh – is known as the “Skipping Sikh” after his exercise videos, which went viral during lockdown last year.

He starts to skip now, but soon stops. Today, he is in the mood to talk.

A love of skipping

My father was born in Amritsar – home to the holiest gurdwara in the Sikh religion – in 1947. His family had a farm – 25 acres of lush, green land where they grew chillies, aubergines, spinach, tomatoes and sugar cane. It was on the farm that his father taught him to skip when he was six years old and on the farm that he started working when he was 10.

“I loved being around the buffaloes, the chickens, caring for the crops,” he tells me. As he worked, he would listen to the prayers from the small gurdwara nearby and watch his father toil, with just as much wonder as he watched him tie his turban. “He was my role model, my inspiration,” he says referring to how hard his father worked on the land. “I felt proud to be his son.”

“The smell,” he continues, remembering the farm. “It was the smell of India – the fresh crops, the buffalo dung.” It is a smell, he says, you carry with you wherever you go – however far away.

And my father did go far. But, for now, his thoughts are back in India, with his father. And I am happy to hear them, although there is always a tinge of sadness that accompanies them.

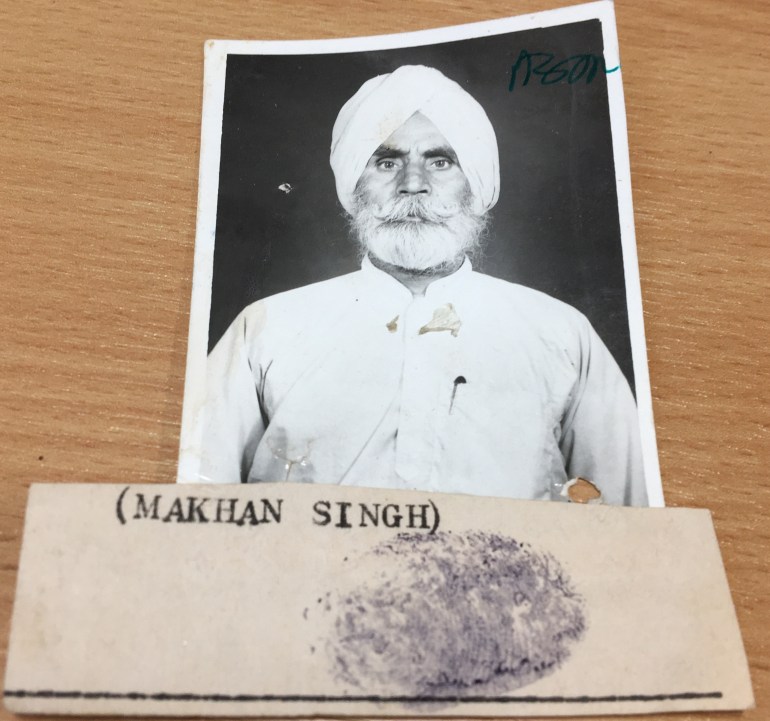

My grandfather was called Makhan Singh, although everyone referred to him as Shah (sometimes used to suggest wealth) because as well as being a farmer he was a money lender. He had fought for the British in Europe during the second world war, returning with stories he shared with my father during his childhood – many of them about the racism he encountered. He repeated them as a warning to my father to always be proud of who he was and to never let anyone make him feel he had to look like them.

Another thing my grandfather brought back from his army service and shared with my father was a love of skipping. He could be a stern man, keen to instil a sense of discipline, hard work and responsibility in my father, but he remembers how on the day he learned to skip, his father hugged him. “It was strange,” he says, “as I had never really seen my father show affection.”

But he also remembers the day, four years later, when his father was arrested. That day, too, was bright and sunny. My father was 10 years old, dressed up in his own orange turban, listening to tadhee (religious hymns) at the gurdwara with his father and two of his father’s friends, when several police officers arrived. His demeanour changes as he remembers it – he sits a little straighter, his voice grows a little louder.

He remembers the words one of the police officers spoke: “We are arresting you, Makhan Singh, for the murder of Mukhtar Singh, son of Sohan Singh.” Mukhtar Singh was a man from the village his father knew in passing. The police said he had been tied to a railway track, where he was killed by a train. And they said my grandfather and his two friends were the ones who had tied him there.

“I couldn’t believe what I heard,” my father says now. “I was shaking and all I could think about was what this would do to my mother.

“My father’s expression was blank, his face went pale [when the police led him away].”

He pauses for a moment, too emotional to continue.

His father was released when the police realised they had made a mistake, he says, but by that point, he had already spent nine months in prison.

My father describes those months as the worst of his life. “It was so painful,” he says, with tears in his eyes. “We couldn’t visit him, it caused a huge strain on the family.” His mother became depressed – snapping at the children and withdrawing into herself.

But then, my father says, he “came home from school one day and there he was on his tractor in the field as though he had never left”.

He ran up to his father, his heart pounding in his chest, and hugged him. But they never discussed what had happened. His father did not mention it, and mine was too afraid to ask. Until this day, he says he still has unanswered questions.

“We were treated differently after the arrest,” he says. “People judge you. They assume you’re guilty.

“Seeing what my father went through and the lack of support from the community was the reason I fell out of love with India,” he adds.

Leaving home

Life continued as it had before his father was arrested, centring around the farm – the spinach, potatoes, onions, chillies and garlic – until my father was in his early 20s and his dad came to him one day to tell him it was time to leave.

“Son, you need to leave this country. It’s not safe for you here, people will be after you and I want you to have a good life,” he remembers his father telling him.

At the time, that meant only one thing: the United Kingdom. “I only knew one family in the UK [an aunt and uncle], but it was a time when lots of people were leaving for there,” he says.

A couple of months later he went to see an agent in a nearby village who, in exchange for some money, would arrange the paperwork he needed for his journey to England.

Six months later, he packed his turbans, his gutka (prayer book) and a few belongings and left India.

“The goodbyes were long,” he says. “Lots of hugs and tears, and my mum checking I had packed everything I needed. It was a very difficult goodbye, very emotional.”

It was 1970 and my father’s first time on an aeroplane. “I couldn’t even sleep because my turban made it so uncomfortable to lean back in the chair and I was worried about it losing its shape,” he explains, smiling at the memory.

When he landed, one of the first things he noticed was how fresh the air smelt and how clean everything looked. “The airport was so big and clean. The streets were so clean; there wasn’t any rubbish anywhere. Not a single car horn could be heard; it was so peaceful and calm. Everyone was very polite.”

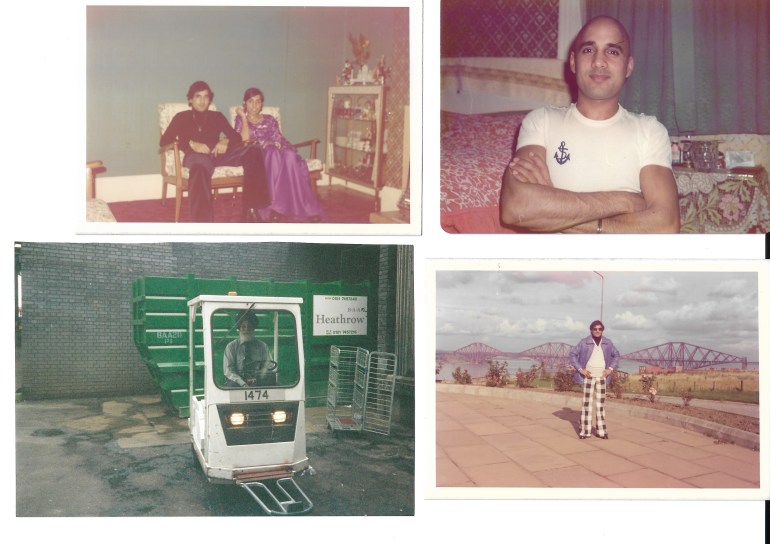

His aunt and uncle met him at the airport and took him to their small, terraced house in the West London borough of Hounslow. It was a simple home, he remembers, decorated in a typically Indian style, but it had two things he had never seen before – a cooker and a washing machine. “It was all alien to me. I didn’t know how to use these appliances and I had to ask my aunt to show me. It felt strange, but I got used to it slowly.”

There were other things about his new home he embraced more quickly – the smell of fish and chips, fresh doughnuts and candy floss, he says. He had to give up the fish and chips when he became a baptised Sikh and vegetarian in 2008, but still remembers the first time he tried it with fondness. “I loved the way it was given in a newspaper and smelt of vinegar. It was delicious. I got addicted,” he says.

Then, there was the smell of flowers in the summer. “The houses were small but people would have flowers in their front gardens and it was really nice how people took the time to look after them,” he says, adding that it reminded him of India.

‘I never wanted to cut my hair’

What did not remind him of India was how calm and quiet it was. “India was so noisy, the car horns, people going around roundabouts the wrong way, the buffaloes. It was constant noise. I didn’t miss that when I came to the UK.”

He didn’t mind the large mirrors either, he jokes, pointing to the one on the wall of our living room. “I didn’t have the luxury of a big mirror like this one when I was in India,” he laughs. “At least here, I’m able to tie my turban properly.”

His turban, however, would soon become an issue in the UK. People would stare at him, he says, and when he applied for his first job – in a bakery where the man interviewing him insisted upon calling him Reg – he was told that he couldn’t be given the job as long as he wore a turban. His heart sank, he says. He was in the UK to earn money that he could send back to his family, but he had no idea how to do that if he couldn’t get a job because of his turban.

He went back to his box room in his aunt and uncle’s house and cried. One morning, shortly after, he woke up in the early hours and crept into the bathroom. There, standing in front of the mirror, he cut off his waist-length hair. “I couldn’t even look at myself in the mirror, I felt so ashamed and guilty,” he says. “I kept thinking ‘what will my parents and siblings say?’”

He felt as though a part of his body – and his identity – had been lost, he says.

He could not bring himself to throw his hair away, so he kept it in a brown plastic bag at the back of the small cupboard in his room.

“I never wanted to cut my hair but I was desperate to get a job,” he says.

My father got the job in the bakery, but the racism did not disappear with his hair. The “politeness” he had noticed at the airport was gone and customers would use racist terms to refer to him. “It was awful,” he says. “It stayed with me for a long time.”

There were more subtle forms of racism as well – less competent and hard-working white colleagues being promoted over him, being constantly made to work the night shift. “I felt that I couldn’t say anything as I would lose my job,” he says. “I had to just ignore what I had seen and get on with it, because as a man of colour I had no choice.”

Then, there were the times when, as he made his way to or from work, people would shout at him to “go back home” from passing cars or through bus windows. His voice becomes quiet as he recalls the time someone threw a carton of juice at him as they shouted a racist remark.

“I would always say ‘God bless you’ to these people as my faith teaches me to love and not to be spiteful,” he says.

‘Your father has expired’

Three years after he arrived in England, my father was introduced to my mother – or rather to a photograph of her through a friend. The following year, they got married in a simple ceremony in a gurdwara in Southall, the part of London my mother is from, followed by a simple honeymoon in Scotland.

A year later, my brother arrived. And I came five years after that. My parents worked hard – both of them often taking on double shifts – to give us a simple life with occasional luxuries. One of those was the cake with strawberries, fresh cream and chocolate flakes my mum ordered for my fifth birthday. It was accompanied by my mum’s home-made samosas and pakoras. In the photos from that day, I’m wearing the bright green dress with matching hair ribbons she made for me and dancing to Bhangra music with my aunties and cousins in the living room of our home with its 1980s brown velvet sofas and colourful carpet. In those photos, everyone looked so happy.

But that night, my father struggled to sleep. He felt as though he was being suffocated, as though someone’s hands were around his neck, he told my mother in the morning. The day after my birthday, he received a telegram from his younger brother telling him his father was dead. “Your father has expired,” it said.

The only way to communicate with his family back in India at the time was by calling the phone in the village post office. The owner would then walk the short distance to my father’s family home to give them a message. With shaking hands, my father dialled the number. Then, we waited. For hours we sat in silence in the living room, waiting for my uncle to call us back. Eventually, the phone rang. My grandfather had been strangled and his body found in a field near the farm, my uncle told him. “I just didn’t believe what I heard,” he says now. My mum immediately set about arranging for my father to return to India.

My father was gone for two weeks. I remember waiting at Heathrow Airport for him to return but barely recognising him when he did. He had grown a beard and his hair was longer. After 15 years without a turban, he had decided to begin wearing one again. “After my dad’s death, his words really hit me,” he recalls. “He had always told me never to change my identity for anyone and I just felt this sudden shiver down my spine as I realised I had changed the way I looked to fit in.”

Along with his new look, he brought back a briefcase. Inside it was the police report into his father’s murder – including a sketch of an outline of a body showing the strangulation marks on his neck. There was also his father’s army uniform.

Nobody was ever charged with the murder.

“I don’t feel the police investigated it properly,” my father says. “I suspect it was connected to him being a money lender and that it was someone we know from the village.”

My father has struggled with never getting justice for him, but since his death he has lived his life in a way that honours his memory – keeping the turban he had grown up watching his own father wear and continuing to skip every day, just as his father taught him all those years ago. In fact, when the UK went into lockdown last year, my dad’s skipping brought him international attention as a video of him skipping at his allotment went viral. He became known as the “Skipping Sikh” and raised thousands of pounds for the British health service, the NHS, through exercise videos designed to keep people active and healthy during the pandemic. He was even awarded an MBE.

“To have to go through years of racism, not feeling welcome in the UK and feeling like an outsider to now being embraced and shown so much love from people and receiving an MBE from the Queen is a real honour,” he says.

Now, he is going to skip the London Marathon for Mencap, a charity that supports people with learning disabilities, in the same month he will turn 75. He finds strength in his faith, he says, adding: “I’d be lost without it.

“It’s a blessing to be able to have a relationship with God. God gives me everything I need in life … and I see God in others. I’m happy, content and grateful for life,” he reflects.