In Nigeria’s Lagos, a bus ride with a stranger who dies of COVID

Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp, a charismatic fixture around Oshodi bus terminal, was trying to get ahead in life.

It was just before 9:45pm on a Friday night in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. Thunder and lightning filled the sky as people rushed to their buses at the crowded and chaotic Oshodi bus terminal. Office workers, school children, women and men trying to make ends meet, and first-time visitors to the city passed street hawkers, all of them trying to survive what was left of the day.

I stood in this crowd, tired and waiting for the next bus home. The downpour started just as my bus arrived. A wet Friday night in Lagos means long hours in traffic, while loud music blares from roadside bars and nightclubs.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

“Ikorodu, 200, enter with your change. No change o,” said the young conductor collecting the fares, warning us to have the exact amount.

I boarded my bus. The beat-up vehicle, poorly maintained and smoky, was crammed with tired passengers talking about life in the city. On my right, a woman with an empty basket described how she had escaped extortion while working in the market that day. The woman on my left complained about the rising price of tomatoes.

Lagosians on public transport swap stories. A good story kills a boring journey and at that moment, I missed my mother’s interludes. She has told strangers about her first pregnancy, the time she witnessed a mob’s “jungle justice” on the streets of Lagos and how I repeated a class in secondary school. She shares her silence too on days when she is really tired.

It was early March 2020 and I was just a few months shy of my 25th birthday. My mother would rarely allow me to move around the city without telling her first where I was going. But I was becoming a man, as my mother would say, and that day I did not need her permission to visit a friend about an hour away without traffic from where I lived in Lagos Mainland.

The women on this bus had my mother’s strict businesslike but jovial air. They all had stories begging to be told, and as they raised their voices over the sound of the rain, speaking about hardship and the increase in food prices, one could tell the common language of this city was chaos.

A passenger on the bus

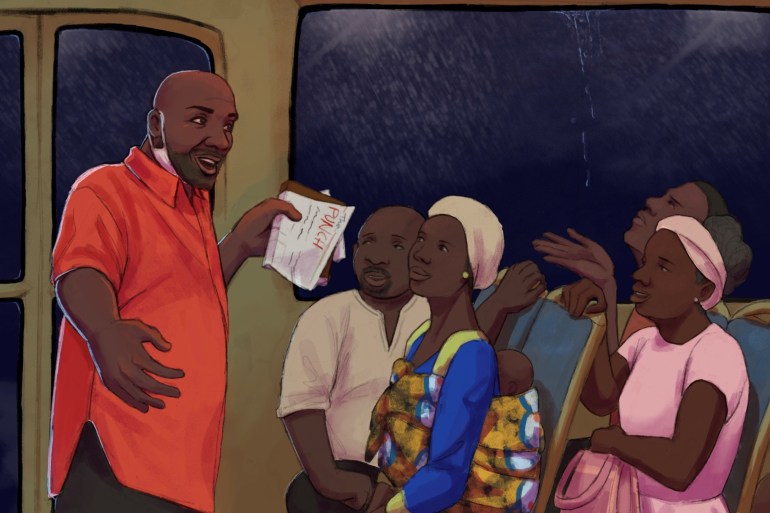

A man stood in the front row near the bus driver with a face mask below his chin, holding a large plastic chequered “Ghana must go” bag, so named because when Nigeria expelled two million undocumented Ghanaian and other West African migrants in 1983, many used them to carry their belongings.

He had entered the bus before the rain started and had volunteered to help the driver by announcing the bus’s destination and calling out to passengers to get on, a common practice in Lagos.

One of the dying fluorescent lights hanging at each of the four corners of the bus lit up his face. A thick scar ran along his left cheek. He wore a rumpled, faded red short-sleeved shirt, black shorts and slippers. He was bald and had an unruly beard. He looked exhausted.

He would later introduce himself as Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp. His English left much to be desired, but his mastery of pidgin was unmatched. His voice was crackly, but the poetry in his choice of words sounded beautiful.

Oshodi terminal, filled with yellow buses, has long been a meeting point for street hawkers, bus drivers and the conductors accompanying them, professionals surviving the 9–5 life, government tax officers, beggars looking for someone to save their day with a Nigerian naira note, petty thieves on the lookout for their next victim, small-time evangelists, and untrained “medical” practitioners with cures for known and unknown diseases. It became Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp’s place of work after he arrived in Oshodi as an adolescent.

His was a trade common among men and women who are trying to make ends meet – Lagos street traders who moonlight as pseudo doctors by selling herbal drugs at night and doing whatever they can during the day. Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp considered himself to be both a doctor and a pastor.

He carried with him the tools of his trades: an old King James Bible wrapped in a page of The Punch newspaper and various drugs packed inside his unzipped bag.

A woman with a baby strapped to her back boarded the bus and he offered his seat near the door to her. He had a big smile and was full of energy as he helped older women board with their belongings and joked with the passengers.

Lagos never houses strangers

His face looked familiar. I was not sure if it was his rounded pot-belly like that of my father’s or the hunger evident on his face, but there was something about him that struck a chord.

I could swear I had met someone like him before on this road, on a bus, somewhere. But then Lagos never houses strangers – we are connected by dreams, struggles, and the desire to be more.

We were held up in traffic and had barely started our journey from Oshodi heading towards Ikorodu when he introduced himself to the passengers, although many already seemed to know him.

Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp said he was in his mid-thirties. He told us how he left Owerri, a city in southern Nigeria, when he was 12, to continue with his father’s trade in medicinal herbs. Jesus, he said, had appeared to him and told him to leave for Lagos. Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp, speaking in the Igbo language, said he was told: “Nwam nwoke, I choro ibu mmadu, je Lagos (My son, if you want to prosper, go to Lagos).”

He talked about the many hurdles he had encountered in life and how he had conquered them all, how he came to Lagos with nothing but dreams of success. Sometimes, he said, God used him to perform miracles. He claimed to have healed a man with staphylococcus, cured a woman who had been barren for 15 years and brought a dead boy back to life.

As he busied himself arranging his bag’s contents on an empty seat in preparation for a night’s work, a woman behind me said she had heard how he had metamorphosed from a boy who slept under a bridge and survived on Lagosians’ generosity into a preacher who doubled as a fake doctor.

Tales like his are often paraded as success stories in Lagos, a place where people say you can be whoever you want to be. And although he did not seem to be prosperous, he evidently gave people hope.

Rasheed, a boy who was probably in his teens and had boarded the bus with me, told me how years earlier Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp had become famous after praying for a mentally ill man in Oshodi. The man, it was said, was cured of his illness, and many believed that Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp had healed him.

But then, in around 2009, Babatunde Fashola, the then-governor of Lagos state, ordered that the shops, shanties and stalls of Oshodi Market be demolished. Many like Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp lost everything. After this, Rasheed said, nobody heard about him for a while.

The rain continued as the night wore on and Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp carried on talking.

He told us how he had converted a Muslim passenger on a previous trip and sold a drug to another that cured him of premature ejaculation. With his charisma and conviction, I was almost persuaded to believe all the miracles he claimed to have performed.

The early days of COVID-19

It was the early days of the pandemic and colourful highway billboards shared public health advice while radio jingles carried information about the coronavirus. There was even speculation about a total lockdown.

But Lagosians continued with their day-to-day lives, many reassured by misinformation and false narratives, sometimes backed by the statements of politicians who downplayed the seriousness of COVID-19.

Oshodi was undaunted – the number of people wearing face masks could be counted on one hand as hugs were exchanged in the crowds.

On this Friday night, I was more concerned about getting home than I was about the pandemic. It was getting late and I had missed two calls – my ringtone drowned out by the sound of car horns and the downpour outside. The first was from my girlfriend inquiring about where I was and if I was staying safe, and the other was from my mother wanting to know if her 24-year-old son knew his way around town.

Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp’s wares

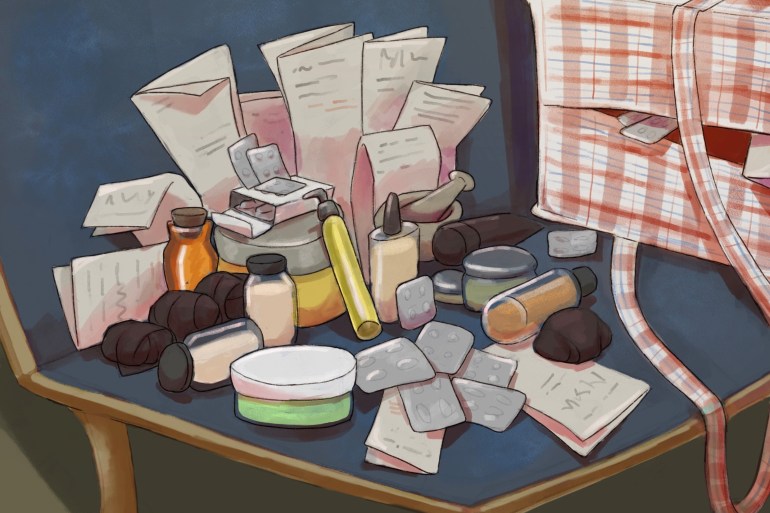

As the bus creaked towards the bridge that connects Oshodi to Ikorodu Road, Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp littered his seat with various drugs and pamphlets – balms, ointments, black soap wrapped in a dark nylon cloth, syrup bottles, and packets of pills cut in half for people who could not afford a full packet. Musician Fela Kuti’s chords played in the background. Some passengers mimed the lyrics, others extolled the political message in a song raging about bad governments.

Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp had the rain and Kuti’s musical genius to battle. He asked the driver to lower the volume of the bus stereo. The driver obliged and Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp raised his voice to match the torrent now battering the bus roof and the complaints of passengers as the droplets leaked into the vehicle.

“Oyinbo [white people] people go enter Owerri for night, come buy our herbal drugs. For day, dem go go yonder talk say our thing na fake, say we no get scientific proof,” he shouted as if he had seen one of these white men who dismiss his drugs sitting in the bus.

He called out the name of each drug and how it should be used. “This one dey cure hepatitis A and B, if you mix am well with fermented sugarcane juice. Take am one-shot for morning, another one-shot for evening. If e no work after two weeks, come my shop for Oshodi, I go return your money”.

An elderly woman reached for one of his herbal drugs as she squeezed a dirty 100 Nigerian naira ($0.24) note into his hands. He displayed more packets, and then prayed for the woman who was now reading the contents of what she had bought. A young man asked with more mischief than innocence if he had a drug for penis enlargement, and another asked if he could help the government with drugs to fight COVID-19, but Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp laughed, explaining how the pandemic was a hoax.

“Everything about the virus na wayo wayo, na dem way be that. We stand gidigba (Everything about the virus is a fake, nothing will happen to us. We are strong), nothing fit do us,” he said, struggling to keep his face mask above his chin.

Grieving for a stranger

I did not hear much about Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp after that night, but before I alighted at my bus stop after spending three hours in traffic with him, people testified about the efficacy of his drugs while he also begged us all to prepare for the second coming of his Lord.

On March 29, 2020, the Federal government declared a 14-day lockdown in Lagos and what followed were dark days in the city: politicians allegedly hoarding palliatives and relief materials, crime and domestic violence were on the rise and inflation was soaring. The Lagos state governor and his health commissioner later tested positive for the virus. Citizens discussed the conspiracy theory popularised by Pentecostal preachers that 5G was the cause of the virus and soldiers opened fire on people peacefully protesting against police brutality.

A few weeks before Christmas, I again found myself at the bus terminal in Oshodi, heading home.

The sky was bright and clear. I was patiently waiting for the driver of the red Tata bus to start the ignition and for his conductors to usher in passengers.

I know trauma does not come with a warning sign, but the day felt so normal. As commuters pushed and shoved towards their buses, a woman selling snacks by the roadside ran towards a young man wearing a white shirt and green trousers, the signature dress of members of the National Union of Road Transport Workers. This group of people are often referred to as Lagos’s landlords. They are always on the streets and are the first to know about anything that happens. She was screaming at the top of her voice announcing the death of Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp.

I was puzzled. I walked closer to the woman to confirm that what I had heard was true. But she was wary about talking to strangers, and would not say much to me.

In my early days at university studying English and Literature, a lecturer once told me that sometimes we could grieve for strangers like we have lived all our lives with them. He said on those days, our desire to find an escape, maybe in art or books, will not help us. That had never had any meaning to me up until this moment, thinking about the death of Pastor Dr Sharp Sharp. Even though he was a stranger, this news stayed with me.

I have tried to find more answers about his death in the stories shared among fellow commuters along my route. Whenever there is someone selling medicinal herbs he is mentioned. Some say he died of starvation because of the lockdown, others that it was malaria – but those who knew him personally believe he died of COVID-19. Others mocked how his faith and his herbal drugs could not save him.

If there is anything Lagos does, it takes as much as it gives. These days, I grieve when I remember him or see people in similar trades trying to earn a few naira notes just to survive.

Sometimes, I doubt his death. On those days, I scan the faces of people in Oshodi selling medicinal herbs, hoping he is somewhere among the crowd.