Melting glaciers, rising seas: Approaching climate tipping points

Glaciers have shrunk at high speed during the last 30 years, raising fears of future land loss and more climate refugees.

There are some extraordinary ‘then and now’ photos appearing in news feeds, alarming pictures revealing the extent of glacier recession in Iceland.

Photographs taken in 1989 and 2020 give a very visual demonstration of how serious our planet’s ice loss is.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWorld’s coral reefs face global bleaching crisis

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef suffers worst bleaching on record

Side-by-side comparisons of the images show how dramatically the outlet glaciers of the Vatnajökull ice cap have receded.

Then: vast reaches of ice and snow. Now: bare rock.

“On surface appearances, the extent of the climate crisis often remains largely invisible,” said Kieran Baxter from the University of Dundee, who documented the glaciers in 2020. “But here we can clearly see the gravity of the situation that is affecting the whole globe.”

A father and son have tracked 30 years of retreat by #Iceland's glaciers ❄️

Dr Kieran Baxter from @djcad replicated images taken by celebrated photographer Coln Baxter to highlight the effects of climate change 📸 🌍

Read the @BBCNews article here 👉 https://t.co/yO7SyK3y0P pic.twitter.com/jybhsSd5HT

— University of Dundee (@dundeeuni) February 1, 2021

Elemental power

I spent a week filming in Iceland for Planet SOS in 2019, perpetually awed by a landscape forged by the supercharged geology, shaped and reshaped by the effects of the elemental power of natural forces.

Basalt rock pinnacles hewn out by erosion stood sentinel on the shore with craggy mountains towering in the distance. Glaciers swept over active volcanoes, ash from previous eruptions carpeting the ice.

Through the millennia the glaciers have advanced and retreated but never has the withdrawal been as drastic as it is now. And it is happening to nearly all the world’s glaciers – from the Alps to the Andes, from Greenland to Antarctica.

I spoke to geologist Oddur Sigurðsson who has been charting glacier loss for decades and is well aware of the global implications.

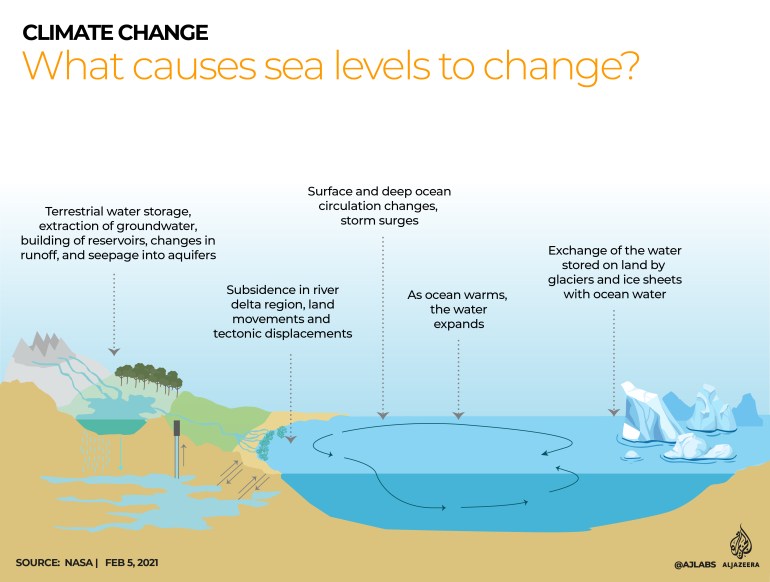

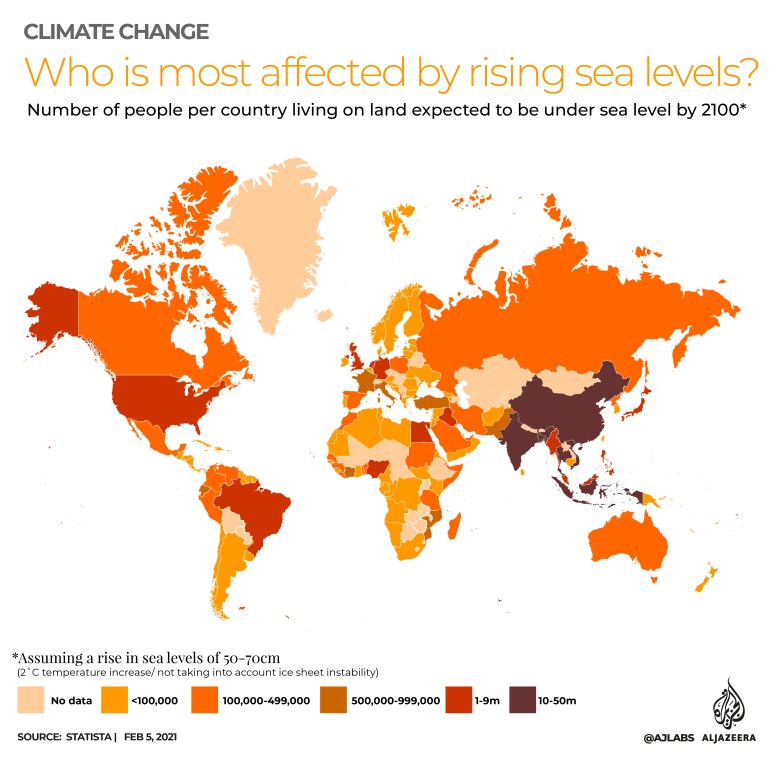

“Glaciers will melt,” he told me. “The meltwater runs into the ocean and the ocean surface rises. I told my friends in the United States, that the refugees would not only be coming from Mexico and Central America but also from Florida and the Atlantic coast.”

Think of that. Refugees from the Atlantic coast, refugees from Florida.

Tipping points

The first global ice-loss survey released recently found that melting of the ice sheets accelerated so much during the past 30 years that it is now in line with the worst-case scenarios outlined by scientists.

There was a stunning exchange on the recent Outrage and Optimism podcast which rendered host Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, speechless.

She was told by leading climate scientist Johan Rockström, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, that we have already gone beyond some key tipping points. Losing the resilience of the planet was the nightmare that is keeping scientists awake at night, Rockström said.

“The number one is the canary in the coalmine – the Arctic summer sea ice. We have passed the point of no return, affecting weather systems in the Northern Hemisphere with heatwaves and drought and forest fires. It is impacting the Gulf Stream and causing warm surface temperatures that are accelerating the melting of the west Antarctic ice shelf.”

Rockström went on to say that a number of glaciers in west Antarctica are starting to irrevocably slide into the ocean, crossing another tipping point. “This would likely commit ourselves to one or two metres of sea-level rise.”

Land becomes sea

What does that physically mean? That by the century’s end, a huge proportion of our coastal populations would have had to move. Hundreds of millions of people would be going inland. And what is now perhaps an efficient subway transport system would become the domain of fish and sea squirts. Cities deluged, land becomes sea.

A recent report by Climate Risk Management says that 100 of the world’s airports could be below mean sea level by 2100. Of those, 20 airports handled more than 800 million passengers in 2018, approaching a fifth of the world’s passenger traffic that year.

Like we have said before, you think this pandemic bad? We ain’t seen nothing yet.

Careful caretakers

“It is a last warning system from science,” Rockström said. “Science is saying we have learned so much, here are the red flags. We can deviate away but that requires cutting emissions by half every decade and reaching a net-zero world economy in 30 years time.”

And crucially, Rockström added, we need to keep all remaining natural ecosystems intact.

“We need to become very, very careful caretakers of oceans and all the natural ecosystems on land. Then we can still avoid the most catastrophic outcomes.”

These are warnings we hear time and time again, only they’re becoming louder and more urgent as science reveals reality, just as surely as the glaciers reveal bare rock.

Your environment round-up

1. UK PM risks ‘humiliation’ over coal mine: A leading climate scientist has urged Boris Johnson to halt production at a new coal mine in Cumbria. “You have a chance to change the course of our climate trajectory … Or you can stick with business-almost-as-usual and be vilified around the world,” James Hansen, the former top global warming researcher at NASA, wrote in a letter.

2. Meat and politics between Tibet and China: Tibetan Buddhist monks are urging former nomadic yak herders to embrace vegetarianism, while local authorities hope to bolster the industrial production of yak meat for a Chinese public that is consuming more meat than ever before.

3. Our unnatural disasters: Thanks to climate change, the world is seeing more wildfires, storms, and new viruses than it did in the recent past. Although we name them “natural” disasters, some say we should call them out for the man-made catastrophes they really are.

4. A freshwater Arctic Ocean?: During the Ice Ages, the Arctic basin was isolated from the world ocean, and may have swung between being filled with salt water and fresh water at different times, according to a recent geochemical study of marine sediments.

The final word

Tipping points are so dangerous because if you pass them, the climate is out of humanity's control: if an ice sheet disintegrates and starts to slide into the ocean there's nothing we can do about that.