A journey through Chile’s conflict with Mapuche rebel groups

Lucia Newman travels to the heart of a rapidly escalating conflicting, speaking to those involved, including the elusive leader of the main armed Indigenous rebel group.

“The possibility of rebuilding the Mapuche nation is on the horizon of many in the Mapuche movement.”

Hector Llaitul, leader of the CAM

The south-central region of Chile is breathtakingly beautiful. There are snow-capped volcanoes, lakes and rivers, and majestic Araucaria trees that are hundreds of years old. There are endless forests and wheat fields. And, until 150 years ago, it was all Indigenous Mapuche territory.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChile’s Mapuche people vs the State: A battle for ancestral lands

Chile’s Mapuche step up fight for basic rights

As COVID cases spike, many Chileans fear toll of another lockdown

The Mapuche call it Wallmapu, which means “men of the earth” in their language, Mapuzugun.

The majority of the Mapuche live in Chile, but there are also some on the other side of the Andes Mountains, in Argentina. They were renowned as fierce warriors. Unable to conquer them, the Spanish colonialists recognised the Mapuche – or Araucanos, as they called them – as an autonomous, independent nation, stretching thousands of kilometres south of the Bio Bio River.

When Chile became an independent country in 1818, the southern border of the new republic ended where the Mapuche nation began. But Chile decided to expand southwards. In a series of military campaigns from 1861 to 1883 – called “the pacification of the Araucanía” – the once-prosperous Mapuche people were pushed off their land and plunged into poverty.

From simmering conflict to full-blown confrontation

Chilean forestry companies now own and exploit the lion’s share of this land, while the Mapuche earn approximately 60 percent less than the average Chilean and live in substandard and overcrowded conditions, often without access to potable water or electricity. More than half have not completed secondary school, and many of their parents never learned to read and write in Spanish.

But this is not where the story ends. What had been a simmering conflict between the Mapuche and the Chilean state over inequality, land ownership, discrimination and cultural identity since the end of the 1800s has today exploded into a full-blown confrontation.

In the last few years, the Araucanía region has become the scene of continuous clashes between Mapuche communities that want to take over what they claim as their ancestral land, and militarised Special Forces police, who have been accused of abuses of power, human rights abuses, fabricating evidence against Indigenous activists, and killing unarmed Mapuche.

The most high-profile case was that of Camilo Catrillanca, who was shot in the back by police as he was fleeing on a tractor in November 2018. The case outraged Mapuche communities and led to an escalation in the confrontation, spurred on by a younger, better-educated generation of Mapuche who believe that it is time to take back what they regard as their land and autonomy.

Armed Mapuche groups have long carried out daily attacks against Chilean forestry companies, large farming estates and other economic interests. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of equipment, trucks and property have been destroyed.

But more recently, even small Chilean farms have been targeted and Chilean civilians have been attacked or killed – something that rarely happened before – while scores of homes have been torched.

Now, people who have lived there for decades say that it has become like the Wild West, and that the government has abandoned them.

Targeting journalists

On March 27, high profile Chilean television journalist Ivan Nunez and his cameraman, Esteban Sanchez, were ambushed and nearly killed.

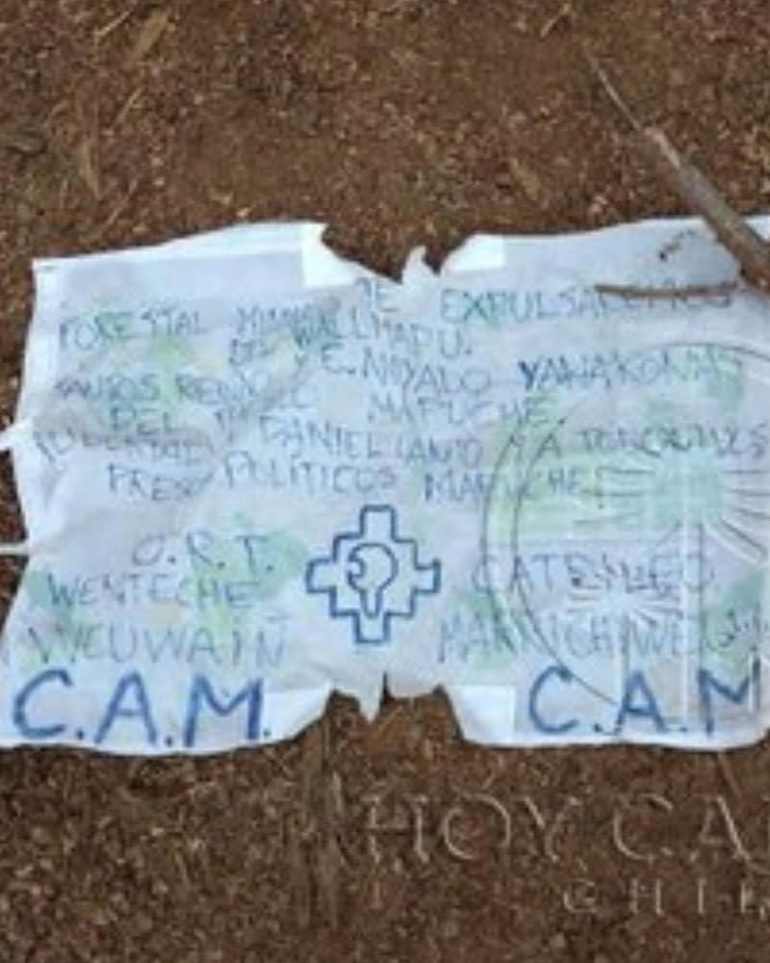

They had travelled to the region to produce a special report on the conflict, and had just come from a meeting to finalise plans for an interview with the leader of one of the principal Mapuche resistance groups, the CAM (Arauco-Malleco Coordinator), when their vehicle came under heavy gunfire.

The attack lasted almost five minutes, during which Sanchez was hit three times. He was left blind in one eye. Nunez was also wounded but managed to drive their vehicle to safety.

My crew and I were preparing to fly to the region – our second visit in six months – when we heard of the incident. Until then, journalists had been caught in the crossfire but had never been specifically targeted. We debated whether to cancel our trip, but decided to go ahead.

I wanted to understand why previous attempts by moderate Mapuche leaders and successive Chilean governments to contain the conflict had failed so miserably.

An interview with an elusive leader

For more than two decades, the CAM has carried out armed sabotage attacks, primarily on the assets of forestry companies. It is still the largest and most organised Mapuche armed group, but it is no longer the only one.

Younger, more radical and less disciplined groups are springing up, and unlike the CAM, many of them are equipped with modern assault rifles and even camouflage uniforms. These newer organisations rarely coordinate with others, they have no apparent leader and their tactics are more violent. The name most often mentioned is the WAM (Weichan Auka Mapu), an umbrella group made up of several other groups who answer to their own leaders.

In the context of this rapidly changing scenario, the elusive leader of the CAM, 53-year-old Hector Llaitul, agreed to an interview, the first with an international news organisation in many years.

Llaitul was born in southern Chile and studied Social Work at the University of Concepcion, where he became a member of the Leftist Revolutionary Movement (MIR). During Chile’s military dictatorship (1973-1990), he joined the Manuel Rodriguez Patriotic Revolutionary Front (FPMR), a Marxist guerrilla group that fought against General Augusto Pinochet’s regime. Then, in 1998, with other Mapuche leaders, he formed the CAM to fight for the recovery of Indigenous land and cultural and political rights.

He agreed to my request to meet in a place that would guarantee security for us all – after all, the attack on the Chilean TV crew had taken place just after they had met with Llaitul, in what was assumed to be an area he controlled. I decided on a discreet house I had rented for the occasion on the outskirts of Temuco, which is under lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When he arrived – at a date and time of his choosing – he was dressed in civilian clothing and accompanied by a woman I assumed to be his partner. He was serious, but also nervous – his eyes often shifting towards the window through which he could see the street beyond the curtains. It reminded me of the time I interviewed a Colombian ELN rebel leader in an area he did not control.

Llaitul has spent much of his adult life on the run. He is labelled a terrorist by the Chilean government and has been arrested numerous times, accused of attempted murder, acts of sabotage and illegal possession of weapons.

In 2017 he was apprehended and charged with a series of crimes under Chile’s anti-terrorism legislation, as part of an intelligence police case called Operation Hurricane. But he was released a year later after it was revealed that the police had manipulated evidence.

He was anxious to discuss the CAM’s decision to consider entering into talks with the Chilean state in order to explore a political solution to the escalating confrontation. But, first, he wanted to make something clear.

“The fact that there are other groups (in the conflict) is something new in the scenario of confrontation between our people and the state,” he explained, choosing his words carefully.

“The CAM cannot be put in the same sack as all the other groups. We have nothing to do with actions where lives were lost. We have been very clear about this. Since the creation of the CAM more than 23 years ago, we have taken on direct actions and territorial recovery processes against forestry companies, hydroelectric companies or other capitalist investment interests.”

He clearly does not want the CAM to be associated with the more extreme forms of violence that have been taking place, and staunchly denies that his group targets civilians.

‘Our historical enemies’

Llaitul also claims that hired gunmen – possibly Mapuche – are working for forestry companies and that they were behind the ambush of the Chilean TV crew.

“Who would be interested in silencing an interview like that one?” he asked, leaning forward as he spoke but never changing his tone.

“We think that there was an intention to silence an authorised voice, like ours, because of the proposal of resistance we are carrying out,” he added, explaining that this was one of the reasons he had granted Al Jazeera an interview.

“And clearly those who are most interested in silencing our voice are our historical enemies, the forestry companies, that are deeply involved in the conflict.”

Chile’s two largest forestry companies have multi-billion dollar investments in the region and are politically influential. But there is no irrefutable evidence to back claims that they are arming groups to defend their interests.

Asked specifically about Llaitul’s claims, Chile’s largest forestry company, MININCO, issued a statement saying it would not respond to allegations made by “terrorists”.

‘The only difference is the method, not the goal’

The situation has long gotten out of control.

Armed attacks are taking place every day against cargo trains, transport trucks, summer homes, large haciendas, municipal buildings, churches and, of course, forests and forestry equipment. White Chileans (referred to as winkas, or outsiders) are being killed, as are police and Mapuche. The death toll is not high, but it is rising. And when the authorities respond, they do so as if going to war, in armoured trucks.

Last September, I attended a historic meeting that for the first time brought together representatives of Chile’s executive, legislative and judicial branches, with several dozen moderate loncos (Mapuche community leaders) and machis (healers and spiritual leaders). It aimed to increase trust between the two sides and to present an alternative to the more hardline groups.

Outside the meeting hall, dissident Mapuche communities protested and denounced their moderate counterparts as “lackeys” or servants of Chilean capitalist interests.

Jaime Huenchumir, the president of the Mapuche Economic Confederation, was the master of ceremonies at the ultimately unproductive meeting.

Six months later, I met him again in Temuco, where he explained that one of the key problems is that the government wants to pick and choose with whom to negotiate. But Chile’s president, Sebastian Pinera, has said on numerous occasions that he will not discuss Mapuche grievances with those who use violence and terrorism.

“The only difference that exists between the various Mapuche groups today is the method, not the goal,” Huenchumir told me. “Some believe it is through violence, others dialogue. But all believe that land, cultural and economic rights are urgent. Regardless of the different leaderships, the demands are the same. The state will never advance towards a political solution if they wait for a single leader to emerge.”

A time for dialogue

The CAM’s leader, Llaitul, concedes that intolerance on all sides is making the dispute impossible to resolve. And that is why he wanted to discuss the seemingly unthinkable: the possibility of entering into a dialogue with the Chilean state.

A deep distrust of Chilean institutions and the conviction that successive governments would never recognise Mapuche demands, has made Llaitul shy away from such a discussion – until now.

“First of all, the committed parties must sit down, and they must be truly committed. It’s not about just sitting down with the institutionalised Mapuche movement that has already been co-opted by the system,” Llaitul explained.

“The ones who have to sit down are those who represent the Autonomist Movement and particularly those of us who are part of the Mapuche resistance, who represent the real counterpart in this struggle, in this confrontation,” he added, becoming more energised.

What would be the other conditions for a dialogue, I asked?

“If the dialogue takes place at a local level, at the level of the Chilean state, it won’t offer many guarantees. That is why we have accepted or at least see with interest, a proposal made by Senator (Francisco) Huenchumilla, that raises the possibility of guarantors, international observers, maybe from the UN or NGOs, or international bodies that relate to Indigenous or human right groups,” he answered.

It is a mechanism similar to what the Colombian government and the FARC rebels used to ultimately negotiate a peace accord in 2016. At the time of writing, President Pinera had not responded to the proposal.

‘From the moment the Spaniards arrived, we’ve been stigmatised’

But it is obvious that there is little time to waste if progress is to be made in resolving the conflict.

Llaitul points to the government’s insistence on equating Mapuche violence with terrorism, describing it as a dangerous evolution of Chile’s national security doctrine in which the Mapuche are defined as the internal enemy – and one which could impact public sympathy for Mapuche demands.

“From the moment the Spaniards arrived, we’ve been stigmatised in some way, as barbaric Mapuche savages, soulless …. And then we became drunk, lazy, when we were left with little or no land and we were subjected to blood and fire.”

It is a theme common in Chilean depictions of Mapuche men, in particular.

“Afterwards came the idea of the ‘good Mapuche’ vs the ‘bad Mapuche’. And nowadays the concept has been installed of the ‘Mapuche delinquent’, the ‘Mapuche terrorist’ and more recently, the ‘Mapuche narco-terrorist’,” Llaitul added, with irony.

I asked him about allegations that the CAM is linked to drug trafficking and also that it receives economic aid from Venezuela.

“Those are all political and police strategies that are spread by the media in order to vilify the Mapuche cause,” he explained. “But the Mapuche cause is not linked to drug trafficking. We say categorically that there are no funds that come from drug trafficking.”

Ties to Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution were not financial but ideological, he suggested.

“As a leader of CAM and of the Autonomous Movement in general, I can say that we have always been accused of having ties to everyone, from ETA to the FARC, at some point even the Taliban. But that’s absolutely false.”

He remained vague, however, about where the CAM does get its money or how much it has at its disposal.

While there may not be massive amounts of drug trafficking in the greater Araucania region, police have found marijuana being produced in a few Mapuche communities. And it is well known that there is widespread timber trafficking in the region, estimated to be worth $200m a year, carried out by Mapuche and non-Mapuche.

‘Politically explosive’

Amid the explosion in the number of attacks on land owners, farms and forestry companies, President Pinera is under pressure from the conservative parties of his coalition and, in particular, the business and agricultural sector of southern Chile, to declare a “state of siege” so that he can send in the army to regain control of the region.

But a high-ranking regional government official in Temuco told me, off the record, that he believes “sending in the army is too politically explosive”.

“The president doesn’t want to risk being held accountable for any human rights crimes committed by the military. And the police are demoralised because of recent convictions in this region for human rights violations and the scandalous revelations that some of them manipulated evidence to prosecute Mapuche extremists. The police can be near an attack or land grab and not move a muscle,” he said.

Angry landowners I spoke to accuse the Chilean state of leaving them to their fate.

Now, just as happened in Colombia, there are reports of “self-defence” groups being organised to counter Mapuche gangs. Although I was not able to independently verify these reports, an official police document acquired by CIPER (Chile’s Investigative Journalism Centre) expresses concern that a group of 35 armed people under investigation “could evolve into a group of paramilitary nature”.

‘We’re tired of waiting’

When I arrived in the Araucanía, I contacted a huerken, or spokesman, for a Mapuche community, whom I had met earlier in one of the more conflict-ridden areas, near Lake Lanalhue. He told me that the situation in his particular community had become very tense and that it was no longer safe for me to visit, as we had previously agreed.

Mapuche leaders always underscore that each Lof (community) makes its own decisions, but compared to my previous trip in September, there seemed to be less coordination among the more militant communities. Or perhaps it is just that the confrontation is becoming more chaotic.

Going into the conflict zone is like entering a different world, with different codes, a different culture and language. Outsiders are deeply mistrusted, especially journalists. Unless you are introduced by a Mapuche they trust, you are likely to be expelled. In Temucuicui, two Mapuche men saw us filming a bus stop full of bullet holes and told us in no uncertain terms to leave “if you know what’s good for you”.

But over time, my crew and I were fortunate to gain access to a few Mapuche families who have taken over land and claimed it as their own. Carolina Soto and Joel Guajardo are both huerkenes of their respective communities in Collipulli, another so called “red zone”. I had met them in September, so they allowed us to visit them. I found Guajardo digging a well on property he had cleared two months earlier and which legally belongs to a forestry company. He has built a small cabin for his wife and three children. There were chickens and geese running freely. He says he plans to plant wheat and vegetables in the spring (winter is about to begin in the southern hemisphere).

“For too many years the Chilean state had us cornered. They reduced our land to almost nothing. My parents owned only three hectares to divide up among all eight of us brothers. We need land to exist! What we want is territory, not just a handout of a few hectares, so that our children won’t keep living in poverty like beggars. We’re tired of waiting, so as Mapuches we’ve made the decision to occupy and work our land, because Chile has a historic debt towards us,” Guajardo told me.

His hands are covered with callouses, but he and his family seem happy – even though they have no water or electricity in their small cabin and the Special Forces police could expel them at any time.

‘Rebuilding the Mapuche nation’

Six months ago I needed to search for signs of land occupation. Now, everywhere I went I saw Mapuche flags and banners reading: “ancestral territory in process of recovery”.

In Collipulli, one community alone has taken over at least 10km of land, not hidden in the forest, but along the main highway. Some of that land officially belongs to forestry companies, other parts to large or medium-sized farms. Hundreds of enormous properties are being claimed. As in the case of the Guajardo family, militarised police move in and try to expel them. But the communities return time and time again, and, eventually, the police seem to give up.

This is what Llaitul describes as “recovering territorial control” of the Wallmapu; a precondition, he says, for rebuilding autonomy and reconfiguring the map of the Mapuche nation on what was their ancestral land.

Is he suggesting turning the clock back 150 years, I asked him?

After a long pause, he replied: “The possibility of rebuilding the Mapuche nation is on the horizon of many in the Mapuche movement.”

He explained the process by which this takes place.

“When we fight and carry out actions, there is first a process of eviction, then comes the occupation and the transformation processes so that another kind of relationship can be rebuilt or reproduced. A social, ideological, cultural, spiritual fabric. That is the Mapuche world. This implies that our strategic horizon is a revolutionary, autonomist and separatist position, as was the Mapuche nation south of the Bio Bio River before.”

The CAM leader added that he envisions a newly independent Wallmapu as a nation without political parties, the church, NGOs, or anything else identified with Western culture, particularly capitalism.

But not all Mapuche people share this vision. Approximately 12.5 percent of Chile’s population identifies as Indigenous, the vast majority Mapuche. Yet despite this reawakening of Mapuche historical demands and ethnic pride, the vast majority do not support a divorce from the Chilean state. For many, autonomy could take the form of self-government and the recognition of language and traditional authorities.

Llaitul concedes that the format of an autonomous Mapuche region will ultimately have to be decided by all of the Indigenous communities.

“Within the Autonomist Movement we have our differences as well. There are some that are comfortable with a type of autonomy within the framework of power of the capitalist system, with capitalist definitions. But for the Autonomist Revolutionary Mapuche groups like the CAM, we want the reconstruction of the Mapuche nation outside of the capitalist system,” he explained.

‘For generations, Mapuche parents changed our names’

That discussion is still a long way off. Right now the Mapuches I met who live in impoverished communities are concentrating not only on obtaining more land, but on recovering respect, as well as their culture and language.

“For generations, Mapuche parents changed our names and surnames into Spanish ones, and refused to speak Mapuzungun at home, hoping that this would shield us a bit from discrimination. But it did not,” explained huerken Carolina Soto, on whom it is an issue that clearly weighs heavily as she tries to learn the language of her people.

Increasingly, divisions and hostilities are mounting among Mapuche communities who recognise the Chilean state – warts and all – and those who opt for confrontation.

“I can say very responsibly that 70 percent of the Mapuche people embrace the institutional solution. The more hardline, radical sectors, with all the legitimacy that they may also have, are a minority,” explained well-known Mapuche writer Pedro Cayuqueo during a Zoom interview.

In the countryside, we visited Mapuche families who had been attacked by masked youths who accused them of being yanakonas, which loosely translates as “slaves of the rich”, or “traitors”.

‘It is a very sad thing to fight against our own brothers’

For more than 30 years, 76-year-old Eduardo Curipán has worked for a landowner who also provides drivers and machinery to forestry companies. Curipán’s employer paid him to keep several harvesters on his property at night for safekeeping. But three weeks ago, in the early hours of the morning, a group of armed men burned down the machinery and fired rounds into his house. He showed me where two of the bullets had entered his home, close to where his family was hiding.

Camilo Sanchez, 42, of the Boroa Mapuche community, took me to see where his family’s land had just been torched. The fire almost reached their homes. Now, he fears reprisals for talking about it.

“Here, they burned between 3,000 and 5,000 bales of dry grain to feed our animals. They did it because we didn’t agree with their violent, radical methods of land takeovers. We fully support Mapuche demands for land. We need more land, too, but not the terrorist methods that are discrediting the Mapuche people,” said Sanchez.

Sanchez and his neighbours have applied for land grants from the state institution in charge of distributing territory to Indigenous communities. But he concedes that he may never see it.

“Maybe my children will,” he reflected.

As I am writing this, a new arson attack has just destroyed a school and a tourist bureau in Lleu LLeu, where several Mapuche leaders have been accused by the CAM and other Autonomous Movement groups of being traitors. In a statement, leaders of 13 Mapuche communities from Lleu Lleu justified negotiations with a forestry company to obtain land.

“Yanakona are those who attack their Mapuche brothers in cold blood,” their statement read.

If nothing else, Hector Llaitul agrees that the Mapuche should not be fighting each other.

“One thing is to fight the forestry companies directly. But another is to fight Mapuche against Mapuche. History has shown that there have been traitors and Mapuches fighting each other. But today, in this situation, it is a very sad thing to fight against our own brothers, even if we are on opposite sides of the fence.”