Tales from an Indian crematorium

Crematorium workers are struggling to cope with the numbers of dead from COVID in India.

Listen to this story:

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh – Deen Dayal Verma has never burned as many bodies as he has this year.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia COVID crisis: ‘Lack of oxygen killed him, not the virus’

India COVID crisis: ‘Our mother has two swords over her head’

India COVID crisis: ‘My dad still doesn’t know my mum has died’

Sitting under the shade of a cement roof at a crematorium in Barabanki city, the 55-year-old who has been a crematorium worker for the past six years, says with a wry smile: “Actually, no dead body has come today. Has COVID-19 come to an end or are the bodies being taken to other crematoriums?”

In India, where cremation on a funeral pyre made from wood has long been part of an elaborate ritual to honour the dead, the religious significance of laying the dead to rest has been all but abandoned as the bodies stack up during the second deadly wave of COVID.

As Deen Dayal waits for the work to come in, he puffs on a bidi (a mini-cigar filled with tobacco flakes and wrapped in a tendu leaf tied with string).

“I have not kept count of the bodies, but in April and May, I worked from 5 in the morning until midnight every day. I think I would have lit more than 100 funeral pyres in April alone. There has been no end to the dead bodies coming to this crematorium,” he says. “Before the second wave of COVID-19, three to four dead bodies used to come in per week.”

Deen Dayal is the only person still working at this crematorium. He has a small, two-room house allocated to him on the site, where he lives with three of his children – his elder daughter, Soni, 14, takes care of her two younger brothers during the day. His wife has returned to the family home in a village 48km (30 miles) away, where his other four children remain, but Deen Dayal has not visited for two months for fear of passing the virus on to others.

The crematorium has become so busy that Deen Dayal says he no longer waits for the municipal cleaner to arrive each morning – he gets on and does it himself so that families will not have to wait around for the crematorium to be ready.

“Over the last two months, the workload has increased so much that I have now developed a habit of waking up early. I don’t want to make people wait with the dead body; I do not feel good for people waiting with the dead bodies for their turn for the cremation.”

The state of Uttar Pradesh, which is more populous than Brazil, has been the worst affected in India during the second wave of COVID, with people struggling to obtain oxygen, hospital admissions and healthcare. The state has recorded more than 20,787 deaths, with thousands more thought to have gone unreported due to the lack of proper COVID testing. As of June 3, India had officially recorded 337,787 deaths.

‘Family members refuse to touch the bodies’

The once highly respectful ritual of cremating family members has undergone a huge shift as a result of the pandemic, says Deen Dayal.

Before, cremations were an important cultural custom in the Hindu faith. People came in large numbers to pay their respects to the dead before the body was placed on a funeral pyre and burned. According to Hindu scripture, “just as old clothes are cast off and new ones worn, the soul leaves the body after death and enters a new one”. Hindus believe that burning the dead body and, hence, destroying it, helps the departed soul get over any residual attachment it may have developed for the deceased person.

“Earlier, cremations were performed with the utmost respect but now for many of the families, it has become a burden. In many cases, funerals have been reduced to just getting rid of the dead body because people are very scared of contracting the virus,” he explains.

“Many times, family members refuse to touch the dead body, and in many cases the family members insist that I only show them the face once before lighting the pyre, so they can pay their last respects.”

Deen Dayal has never been tested for COVID, nor has he been vaccinated. He has no personal protective equipment (PPE). All he has been given by the local municipal government which oversees the crematorium is a “Corona prevention kit”, containing vitamin C tablets, zinc tablets and five days worth of an anti-parasitic drug.

“I listen to everyone. I wear a mask and gloves, use a sanitiser, although I know that is not enough, but I do not have any other option,” he says.

For the cremation of each dead body, Deen Dayal is paid Rs 500 (about $7) and he asks the family to provide gloves, masks and sanitiser.

His family is terrified by his job – he speaks to his wife and other four children by telephone as often as possible. “There are nine people in my family (himself, his wife and seven children) and they all are very scared of the COVID situation. They keep asking me to stop doing this work but if I stop setting up and lighting the pyres, then who will do it and what will I do? The only work I know is this. If I stop doing it, how will I feed the family?” he asks.

“I try to take precautions to keep myself away from the infection but this is a very risky job. I have to do it because I want to treat every dead body with the utmost respect, otherwise I will not be able to face God when I die.”

‘I see him crying at night’

Deen Dayal’s 14-year-old daughter, Soni, says that the family back in their home village will not allow him to visit for at least four days after cremating a dead body these days – so there is little point in him making the 48km (30-mile) journey there every Tuesday as he used to do. At their lodgings on the crematorium site, he must remain outside at all times.

“To answer nature’s calls he goes out in the fields and does not use the toilet we have access to. He eats and sleeps outside and sometimes he gets irritated when he cannot play with my younger brothers.

“I have seen him cry at night but he never mentions the reason behind it.

“We all know that he misses us a lot and we also miss him. It has been months [since] we have gone out with him in the evening to the markets to eat samosa and do grocery shopping. We miss the bedtime stories about the Gods he used to tell us.”

Soni does her best to care for her younger brothers while her father is working, but it is not easy. One of them – six-year-old Sunny – fractured his wrist while playing.

Back at the family home, his wife and eldest daughter work as domestic help in nearby houses, earning about $130 per month. They say this is enough to feed the family. There is no gas connection to either that home or the crematorium lodgings, so the family uses firewood to cook.

“We tried very hard to convince our father to return to our native village and not do the cremation work but he is adamant,” says a frustrated Soni. “He did not listen to us and is still doing the work despite knowing the large number of people dying from COVID.

“My mother has had arguments with him, but he has never paid any importance to what we were saying. My father has also developed a drinking habit and in the past, he had liver problems, so we are extremely worried for him.”

‘I have to do the job of the priest’

In Belai Ghat, on the banks of the holy Ganges river in Belai, Unnao, Uttar Pradesh, about 64km (40 miles) north of Lucknow, Ankit Dwivedi is telling someone over the phone to make sure the body they have is tightly wrapped in a plastic sheet if they want him to perform a cremation.

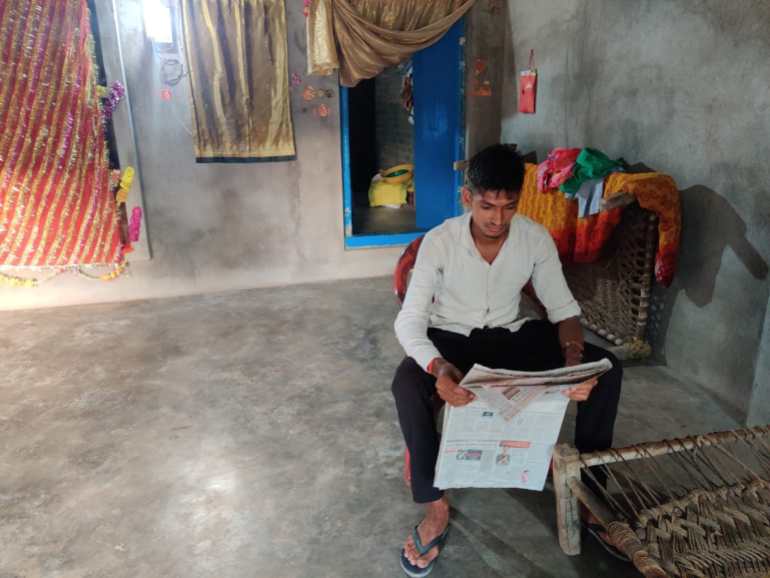

These days, with some priests afraid to oversee cremations due to the pandemic, the 23-year-old crematorium worker also performs their duties. Although he is not a priest and has received no training, it is Ankit who now quickly recites the funeral hymns before lighting a body.

“A lot of people are dying and no one knows the reason [because of the lack of COVID testing],” he says. “There are high chances of COVID being behind this sudden surge in deaths so to protect myself, I have been asking everyone to wrap the dead bodies in a plastic sheet before they come to the ghats [the river banks].”

In more normal times, this is a deeply holy site – the Ganges river is considered the holiest in India. After bodies are cremated, family members bring the ashes from the nearby crematorium to place in the river, in the belief that the soul of the dead person will be cleansed by the waters.

Now, because crematoriums cannot keep up with the workload, Ankit says, more and more families have taken to burying the dead – once considered unacceptable in the Hindu religion. There is no other choice – the crematoriums are full and people have to get rid of dead bodies quickly because of the risk of infection and the social stigma attached to those who have died from COVID.

“This COVID disease has changed a lot of things. People now want to bury their dead ones if they can’t get the cremation done as fast as possible. The reasons behind it are both poverty and fear of COVID,” Ankit says.

“Before the pandemic, 10 to 12 cremations were being performed at this ghat each week but in the months of April and May I have performed at least 25 cremations every week and never in my life have I seen such a large number of deaths. I pray to God to not show us a similar situation ever again.”

Every day is the same for Ankit. “I wake up at around 5.30am and then I reach the river bank by 6am. I stay there all day and eat whatever I get from the people who bring dead bodies with them or else I buy cucumber, watermelon and other things that are grown on the river bank.

“Before the pandemic, I used to pedal myself home on my bicycle in the afternoon for lunch but the situation is not the same now. I have isolated myself as I do not want to harm my family by carrying any kind of infection with me. My parents are older and I fear for them. My stuff has been separated by the family and my dinner is placed outside my room before I reach home.”

Once he is there, he remains isolated in his own room, and no one else is allowed to enter.

Ankit comes from a family of cremation workers. They have been in the funeral business for more than five decades. They have also studied the Sanskrit language, so that they can learn about the cremation rituals in Hinduism.

He used to have a busy life outside of work – but no longer. “Now I cannot even meet my friends or go to play cricket with them. All I do is perform the cremations, eat, sleep and repeat. This has been my routine on loop for the last two months and there is nothing else happening in my life.

“All I care about these days is my stock of face masks and sanitiser because these are the only things that are going to save me from COVID and my family will be safe only if I am safe,” says Ankit.

“I had a habit of massaging my parents’ feet every night before going to bed but now I keep a distance of 10 feet when I am with my mother and only have contact with my father when he comes to leave me my tea early in the morning. This is a really sad feeling because there is no life without family and if this pandemic does not come to an end, then I am sure I will either slip into depression or die from the isolation.”

‘I feel like a vulture who feeds on dead bodies’

The one “bonus” is that Ankit, the sole breadwinner in the household, is earning a good deal more money. The standard fee of Rs 500 ($7) per body he cremates has risen to Rs 2,000 ($28). But the family finds little joy in this.

“Performing cremations is our family business but now I feel like a vulture who feeds on dead bodies,” says Ankit’s father, 50-year-old Vipin Bihari, who has retired from funeral work. “I have never seen such a large number of deaths in my life and my son has to see and work in this unfortunate situation. Our family never thought of changing the profession but now I feel like our kids should do something else.”

Dismayed by the prospect of the family remaining in the cremation business, Vipin says he is considering opening a grocery shop nearby which he can pass on to his children instead.

He adds that his wife desperately misses their son even though he is living in the next room. “Every night my wife asks me to stop Ankit from going to the river bank and performing the cremations but if he stops doing this then what else will we do to earn our bread and butter? She cries, she fights with me. She fights with Ankit too but consoles herself watching the family and understanding that Ankit is the sole breadwinner now. We do not own land and our elder son is sick [with a long-term illness] so all the burden of earning is on Ankit only.”

Ankit says he feels “like I am cheating my religion because people are burying more dead bodies and not burning them as per the religious rituals but what more can I do?

“As my father says, ‘we are no more than vultures’. We feed on dead bodies. The more dead bodies, the more money but no one pays us happily. A lot of time I feel that this money is even worse than begging but this is my life and I accept it the way it is.”