Film festival brings Palestinian history to life

Nearly 60 local and international films were screened during the ninth edition of the Palestine Cinema Days festival.

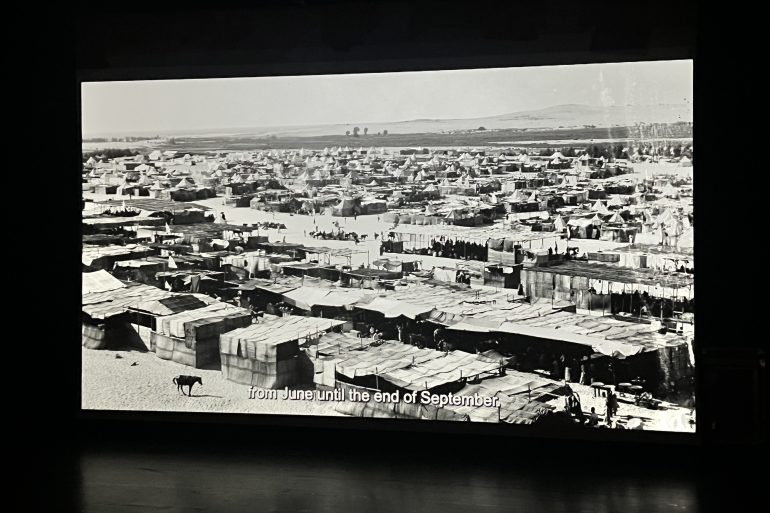

Ramallah, Occupied West Bank – Black and white images of pre-1948 Jaffa, the enchanting coastal city referred to by Palestinians as the “bride of the sea”, shifted slowly across the large screen of the Qattan cultural centre in Ramallah, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

With archival photos from 1930 to 1948, as well as rich sound design and a video testimony of a charismatic elderly man whose family was expelled from Jaffa, director Rashid Masharawi took viewers on an absorbing historical journey that brought Palestinian Jaffa to life.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsMo is the inspiration Palestinian cinema needs

Israel’s war on love

It was one of nearly 60 local and international films screened from November 1 to 7 during the ninth edition of the Palestine Cinema Days festival held annually across seven Palestinian cities. This year’s theme was “voicing visual memory”.

From footage of people working on the docks – whether fishing or packaging Jaffa’s famous oranges – to families and friends enjoying time on the beach, elderly men sitting in cafés smoking shisha, and family portraits, Masharawi left the audience feeling they were present at that moment in time.

“I couldn’t take my eyes off the screen,” my friend, who accompanied me to the screening on November 5, said, expressing the same reaction I had.

Masharawi, who was born in the Shati refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, and whose family was also expelled from Jaffa in 1948, has said the 60-minute documentary film titled “Recovery” is “a cinematic experience that restores their memories as well as ours – as an attempt to restore our relationship with time, space and event”.

Through the memories of the elderly man, Taher Qalyoubi, who was born in 1929, the film touches upon key moments in Palestinian history, including mass uprisings against oppression by the British occupation, and Zionist settler colonialism that culminated in the Nakba – the violent ethnic cleansing of Palestine to create the Jewish state of Israel in 1948.

He recalls the last thing his mother told him and his siblings during their expulsion by Zionist militia on April 24, 1948: “Kids, take a good look at Jaffa, God knows when we’ll be able to see it again.”

Speaking into a camera, Qalyoubi unveils the recurring question in his mind: “Is it possible? Is it possible that all of this happened to Jaffa and Jaffans?”

This is the same question that arises in my mind – and in the minds of many Palestinians, particularly when visiting striking cities such as Jaffa and Haifa, that were ethnically cleansed of their Palestinian residents, leaving us searching for the traces of us in these spaces.

To me, Masharawi’s film does what it set out to do: it succeeds in beginning to mend our relationship with these places and events; it shows us a time when our homeland belonged to us.

Fierce competition

With a rich and careful selection of films, the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, held since 2014 by the Ramallah-based Filmlab organisation, never fails to amaze.

The Ramallah Cultural Palace hall is always filled to the brim on the opening and closing nights of the film festival. Thousands attended throughout the seven days of the festival according to organisers, with screenings across the cities of Ramallah, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jenin, Haifa, Gaza city and Rafah. Different independent fiction, documentary and short films were showcased.

Not only does the festival provide a platform for local films and filmmakers, but it also introduces the Palestinian public to new perspectives through Arab and international films, at a time of political instability and tension.

Each year, the festival also organises the Palestinian Sunbird Award, awarding sizeable monetary prizes, with the top prize of $10,000 granted for film production. Twenty-four locally made films competed this year.

Mish’al Qawasmi, a filmmaker from Jerusalem who won the top prize for his film The Flag, said he was not expecting to win, particularly as this year’s competition was so strong. The prize means he will now be able to fund the production of his movie.

“This year’s competition, in my opinion, was the fiercest so far. The names of the people competing are known and are the rising generation in film. They are the ones taking the next step forward,” he told Al Jazeera during the closing screening on November 7.

“It’s an amazing feeling to win. But the nicer feeling is when you hear everyone clapping and calling your name around you. I have been working in the film industry for a long time, and the biggest prize was seeing all these people happy for me,” he said.

This year, the festival also hosted a subprogram with an array of films marking 40 years since the expulsion of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from Beirut in 1982.

Hanna Atallah, the director of the festival, said the film festival is important because “no one can tell our story like we can”. In any movie, Atallah told Al Jazeera, “the most important question that remains is: who is producing the image”.

The closing film this year featured Farha – Jordan’s official Oscar entry to the 95th Academy Awards 2023 International Feature Film category – starring famous actors Ali Suleiman and Ashraf Barhoum. Made by Jordanian director Darin Sallam, the film is based on the true event of a 14-year-old who was locked in the pantry of her home in a small village during the Nakba.

Through the cracks in the wooden door of the pantry, the viewers live through the horrific events of 1948 through the teenager’s eyes as a silent witness, leaving her changed forever.