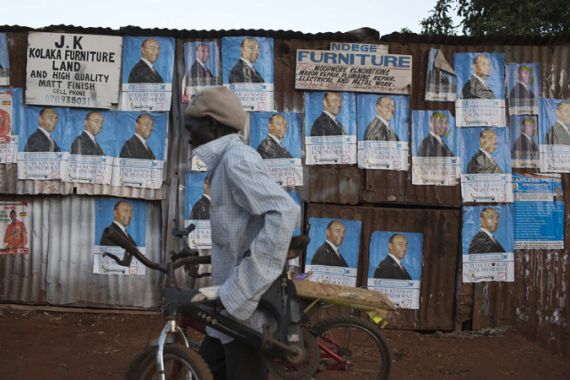

Disinformation, mudslinging induce voter apathy in Kenyan youth

Kenya’s digitally-savvy youth are being exposed to outright disinformation and inflammatory rhetoric on social media.

Nairobi, Kenya – Last year, Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), the country’s elections management body, set a target to register six million new voters for this August’s upcoming general election.

With 2019 census data indicating that nearly five million young Kenyans had reached voting age since the 2017 elections, that goal seemed attainable. But as the voter registration drive came to an end in February, the commission announced that it had only managed to register 2.5 million new voters.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 791

What happens when activists are branded ‘terrorists’ in the Philippines?

Currently, only eight million registered voters – about a third of the total 22 million – are aged 18-35, reflecting an increasing level of apathy about governance and elections among young, potential voters.

Sheila Mwiti, in her mid-20s, is one potential young voter but does not plan to cast her vote in the August election. “I consider myself politically engaged but this election is too dysfunctional for my vote to be meaningful,” the Nairobi-based podcast editor told Al Jazeera.

‘More connected than ever’

Kenya has a high internet penetration rate of 87 percent so its young demographic is highly exposed to political content online, but increasingly too, to outright disinformation and inflammatory rhetoric on social media.

A new report by researcher Odanga Madung of the Mozilla Foundation shows that TikTok, in particular, is a worrying wildcard in this year’s election, with the platform acting as a forum for fast and far-spreading political disinformation.

After reviewing 130 videos from 33 accounts that had been cumulatively watched four million times, the research revealed a moderation ecosystem lacking the context and resources to adequately tackle election disinformation in Kenya.

This has had a disproportionate effect on young audiences, as TikTok users in Kenya are typically aged 14-25. The platform is already the most downloaded app in the country, surpassing even the ubiquitous WhatsApp and Facebook.

Young audiences increasingly not engaging with the formal political process but simultaneously being exposed to incendiary political content on their beloved platform is a signal of trouble ahead, experts say.

“First, this content is not just on TikTok alone,” Madung told Al Jazeera. “For a long time before the alarm bells were rung, this content was everywhere on the big social media platforms. The problem with TikTok, in particular, is that it supercharges virality – you don’t need to build an audience of followers to go viral.”

“It’s no coincidence that at a point where we’re younger and more connected than ever that we have a much higher number of undecided voters and low registration. That disengagement tends to be reinforced by weaponised information environments,” said Madung.

His report also indicates that this political mudslinging is by both camps, triggering a prevailing environment of cynicism among youths.

‘Reinforcing apathy’

One camp is led by former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, a longtime opposition leader now seen as the “establishment” candidate, endorsed by the highest levels of power, including President Uhuru Kenyatta.

The other is that of Deputy President William Ruto, who seems to have taken up the voice of the opposition, but is still formally second-in-command in a government he is now railing against.

That convoluted situation, where a sitting president has broken ranks with his deputy and joined forces with an opposition leader who until recently was his bitter critic and formidable opponent, has left the electorate in Kenya reeling.

Many young voters such as Mwiti and older ones who have seen the games of political musical chairs in the past, still do not know what to make of it. This, even in a country where political deals and party-hopping are commonplace in every electoral cycle.

“The electoral institutions in charge seem disorganised and confused, and what comes out even more strongly is the sense that the outcome is already a ‘done deal’,” she said. “I really don’t think my vote will count.”

And she is not alone.

“The sentiment for a big section of the electorate is: ‘Everyone on the ballot is a crook, so why should I vote? I would rather not vote than vote for the options on the table’,” Madung told Al Jazeera. “We’re finding that TikTok and similar apps go on to drive weaponised political content that might be reinforcing already existing apathy among young voters, underscoring the feeling that there’s no point in participating.”

Experts say that has left this section of the public without the capacity or willingness to join in performing their civic duties.

“We have a large, energetic youth demographic that largely doesn’t have the tools to participate in the formal political process, that is, by registering as a voter,” said Nerima Wako-Ojiwa, the executive director of Siasa Place, an organisation working to educate and empower young people to engage meaningfully with mainstream political processes.

“I’m worried about what this means not just for the upcoming election, but for the democratic process in Kenya more broadly, if young people are feeling so excluded from a system that is supposed to include everyone,” she said.

“That’s the promise of democracy – that every vote counts,” she added. “Clearly, young people in this country don’t think so, and what happens when one day they wake up and say – this is it? I don’t think we’re prepared for that reality.”