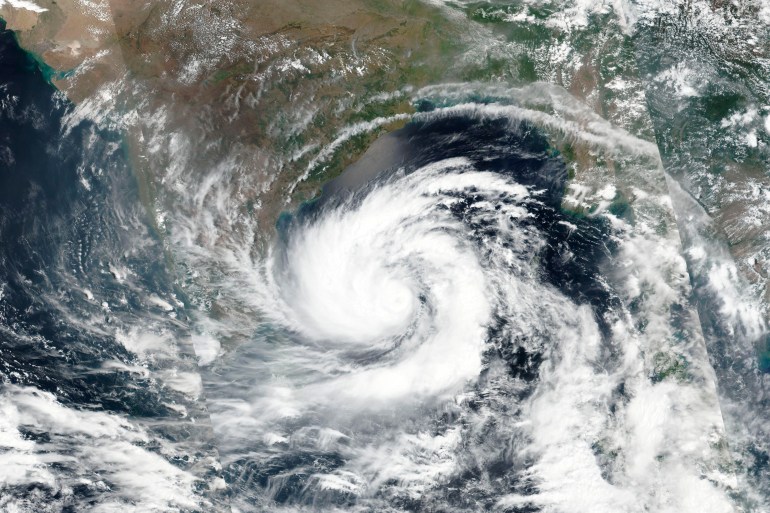

Are storms getting more powerful and dangerous?

From Malawi to Mississippi, deadly cyclones are ravaging the planet. But scientists warn they could get even scarier.

It started off innocuously, like any other tropical storm. But Cyclone Freddy, born off the northwest coast of Australia in early February, was anything but ordinary. It intensified, then headed west and crossed the Southern Indian Ocean, travelling more than 8,000km (4,971 miles) to reach Southeast Africa.

By the time it eventually dissipated after making two landfalls in mid-March, it had become the longest-lasting tropical cyclone in recorded history. It was also the most powerful storm ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere, with its trail of destruction leaving more than 600 people dead and more than 1.4 million affected.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina evacuates over 100,000 as heavy rain continues to lash south

Asia bears biggest climate-change brunt amid extreme weather: WMO

Photos: Highest-level rainstorm warning issued in south China’s Guangdong

Yet, even as Malawi and Mozambique – the worst-hit nations – were desperately pursuing rescue efforts, a devastating tornado ripped through the southern American state of Mississippi in late March, killing more than two dozen people and destroying towns. And late last week, powerful storms and tornadoes struck a vast swathe of the American South and Midwest, killing at least 22 people.

Such deadly storms often exacerbate humanitarian crises in affected societies. Madagascar, also hit by Cyclone Freddy, was already reeling from the effects of deadly tropical cyclones in 2022 that killed more than 100 people on the island nation.

Major storms also leave a legacy of health woes. Mozambique is now battling a deepening cholera challenge amid disruptions to sanitation and water supplies because of the cyclone. Reported cases quadrupled between early February and March 20, crossing 10,000 patients, according to UNICEF.

So are tropical storms growing in intensity? What’s making them so powerful? Is climate change to blame? And can the world prepare better for such extreme weather events?

The short answer: Mounting evidence shows that increasingly warmer oceans are fuelling more powerful tropical storms than before. The link to climate change is clear, say many scientists. There is no quick fix. But alongside cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, poorer communities in the Global South desperately need support with climate adaptation strategies to reduce the risks of death, devastation and displacement.

‘The perfect storm’

Tropical cyclones are strong, swirling storms typically formed over warm oceans, with a minimum wind speed of 119 kilometres per hour (74mph) and with very low air pressure at the centre. They are also known as typhoons in the North Pacific and hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean.

A warm ocean helps cyclones intensify rapidly, said Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune, in a statement to Al Jazeera. Freddy underwent intensification seven times during its lifetime, he said, helped by warm surface and subsurface waters that kept the cyclone alive for a record period of time. These warm waters also consistently supplied moisture to the cyclone – which showed in the floods triggered by the rain dumped by Freddy on southeastern African nations.

Koll described the “persistently warm ocean waters and excess supply of moisture” as “a clear signal of climate change”.

Shruti Nath, a climate data researcher at Germany-based nonprofit Climate Analytics, agrees with that assessment of the factors that made Freddy so powerful and long-lasting.

“Freddy was an unprecedented, deadly cyclone” caused by “a combination of Indian Ocean warming and perfect atmospheric conditions,” Nath told Al Jazeera. “In other words, the perfect storm.”

Yet scientists worry that Freddy’s destructive record might not remain unmatched for too long. Multiple studies in recent years have suggested that human-caused climate change is likely increasing the intensity of tropical cyclones. A review [PDF] of over 90 peer-reviewed articles published in 2021 indicated that the world should prepare for more intense storms over the next century.

Some research also suggests that the actual number of major storms is likely to increase in the coming years. A team of US-based meteorological and climate scientists concluded in 2020 that major tropical cyclones globally are increasing in number by 8 percent every decade.

And if the gradual warming of the oceans isn’t bad enough, the threat of another lesser-known but devastating coastal hazard, also attributed by scientists to global warming, is also growing – temperature surges on the ocean, known as marine heatwaves.

A deadly combination

Marine heatwaves – when the seawater surface temperature is abnormally high for a period of time – are longer and more frequent than ever before. Scientists in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States showed in 2018 that between 1926 and 2016, the frequency of marine heatwaves increased by 34 percent, and their duration by 17 percent. Globally, the number of marine heatwave days grew 54 percent over this period.

They’ve been shown to cause coral bleaching and the destruction of seagrass and kelp forests. This damage to the ecosystems many other oceanic species depend on in turn hurts marine biodiversity, research has shown.

And when a marine heatwave and a cyclone collide, an already dangerous storm can turn into a beast.

In May 2020, Cyclone Amphan barrelled into Eastern India, killing more than 100 people and forcing nearly 5 million people to flee from their homes in India and Bangladesh.

For Babita Jangir, a postdoctoral fellow at Israel’s Volcani Institute Agricultural Research Organization, the devastating cyclone hit closer home. She had previously pursued postgraduate studies at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur. Areas near the IIT, one of India’s top engineering colleges, were ravaged by the cyclone.

Jangir decided to track down the ingredients that had made Amphan one of the most powerful storms to hit India in recent decades. In a study published in 2022, Jangir and her colleagues found that the wind speed of the cyclone had more than doubled from 102km/h (55 knots) to 222km/h (120 knots ) within just 24 hours due to the presence of a marine heatwave.

The study, she told Al Jazeera, showed that “the intensification of a cyclone can also occur due to the presence of the marine heatwave”.

With the regular warming of oceans already expected to increase the intensity of cyclones, more frequent marine heatwaves could turbocharge these storms. Jangir predicts that “long-lived and intense cyclones”, like Freddy, will only grow more common.

Seasons of devastation

The research by Jangir and her colleagues is echoed in findings halfway around the world from the Gulf of Mexico, where oceanographers have also found that a marine heatwave can serve as an energy booster for tropical storms.

But the effects of a warming climate aren’t limited to individual weather events.

Peter Pfleiderer, a researcher at Humboldt University in Berlin, led a study published in 2022 that looked at the influence of ocean surface warming on hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean. The study [PDF], which was co-authored by Nath of Climate Analytics, found that the likelihood of “extremely active hurricane seasons” – which have several very powerful cyclones – had doubled between 1982 and 2020.

“This research was a first step towards attributing extreme hurricanes to human-caused climate change,” Pfleiderer told Al Jazeera.

Extreme hurricanes also bring with them an equally deadly partner – a dramatic rise in seawater levels known as a storm surge, which often leads to the flooding of coastal regions.

With ocean levels already rising sharply in recent years because of global warming, scientists have shown that storm surges and associated tidal waves will get worse in the future, and are likely to dump water farther inland than before.

The direct link between climate change resulting from human actions and extreme weather events is now scientifically evident, Pfleiderer and Jangir both said. The growing frequency and intensity of droughts, heat waves and wildfires around the world has also been attributed to climate change by scientists.

And a new report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released in late February, ominously concluded that there is a “brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all”.

Yet, despite the scientific and anecdotal evidence, scientists worry that large parts of the world remain unprepared.

‘Need more diverse voices’

To a large extent, the global nature of climate change and extreme weather phenomena – where a storm like Cyclone Freddy can span three continents – demands an equally global response.

“We have the technology and capability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally but emissions remain at close to record high levels,” Andrew King, a senior lecturer in climate science at Melbourne University, told Al Jazeera.

Lisa Schipper, an IPCC author and professor of development geography at the University of Bonn, said the “unequal” nature of the problem made it particularly challenging. Schipper’s work focuses on the intersection of climate change and human development. The Global North is responsible for more than 90 percent of the world’s excess greenhouse gas emissions. And within countries, the “wealthiest people are the ones who contribute most” but are also the ones who resist change the most, Schipper said.

“In the end … a small lot of people are causing the most damage,” she told Al Jazeera.

Still, there are more immediate steps that can also help countries avoid the worst of the death and destruction that are the calling cards of dangerous storms, say scientists.

In particular, robust early warning systems are important, said Jangir, the researcher at IIT Kharagpur. A 2019 report by the Netherlands-based Global Center on Adaptation concluded that a day’s advance warning of an imminent storm or heat wave could reduce damage to people and their property by 30 percent.

And Bangladesh has shown how even a country with limited resources can save thousands of lives by putting in place a robust disaster preparedness system. After a deadly cyclone killed an estimated half a million people in 1970 in what was then East Pakistan, the new nation of Bangladesh that was born a year later set up a cyclone warning and response system that it has honed over the years.

Today, it relies on embankments to blunt the force of cyclones, thousands of shelters to house displaced people and text alerts sent out to warn communities about coming storms. Tens of thousands of volunteers man this response system – from helping people evacuate to ensuring that the shelters are stocked with food, water and medicines. This has helped dramatically reduce the death toll from deadly cyclones like Amphan, which claimed about two dozen lives in Bangladesh.

But while United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres has promised early warning systems for all nations by 2027, that won’t be easy: As of October 2022, only half of the world had such systems in place.

That’s compounded by a more fundamental knowledge gap. Most climate-impact research has focused on rich countries.

“While extreme events are becoming the norm across the world, a lot of on-the-ground impacts are poorly documented in more vulnerable regions,” said Nath of Climate Analytics.

Currently, climate adaptation strategies – even when meant for developing nations – are often devised in the West, following little or no collaboration with local communities, said Schipper. “A policy framed in a capital city like London could be implemented somewhere in Asia.”

That needs to change, she said. “We need more diverse voices to get more accurate knowledge and solutions,” Schipper said.

“We are leaving behind a lot of people.”