Toxic legacy

The fight to end environmental racism in Canada.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.

Aamjiwnaang First Nation - When industrial warning sirens blare through Chemical Valley, Arnold Norman Yellowman hears the neighbourhood dogs howling in this small Indigenous community in southern Ontario, Canada. “They actually sing with the sirens,” he says.

Yellowman, 38, has developed a deep - and profoundly undesired - connection with the pollution surrounding his family in Aamjiwnaang First Nation. When trucks rumble along the road at night, the vibrations resonate throughout the home he shares with his partner and their three young children. When he steps out onto his sunny back porch, he can sense the chemicals in the wind.

“That’s the north wind. It comes from Esso or Imperial Oil,” Yellowman tells Al Jazeera, tracing his finger across the sky. “If the wind blows from this direction, it’s Suncor - used to be Dow. And if the wind blows over this way, it’s Shell, ethanol, Dupont. If it blows from the south, it’s Nova Chemicals.”

Yellowman, who has lived in Aamjiwnaang for close to three decades, worries acutely about the health effects of growing up in one of Canada’s most heavily industrialised areas.

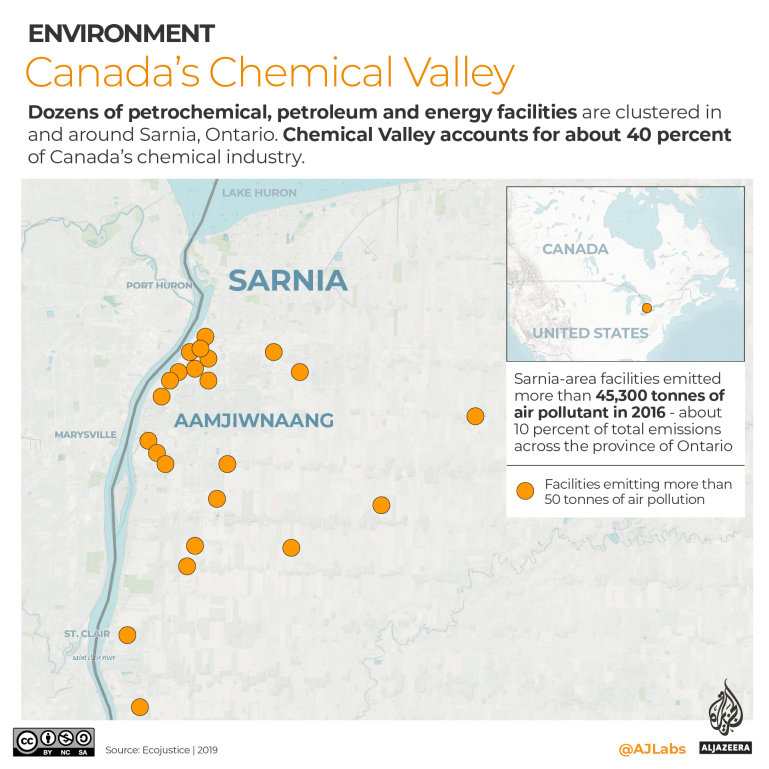

Chemical Valley is centred around Sarnia, Ontario, a city of about 74,000 people at the southern tip of Lake Huron, just across the border from the US state of Michigan. Aamjiwnaang, home to about 900 people living on the reserve, is a short drive from the city centre past rows of towering oil storage tanks, gas flares spitting flames into the sky, and other fenced-in infrastructure. Speakers are affixed atop tall wooden poles throughout the community, ready to blare warning sirens in an emergency.

In 2016, more than three dozen petroleum refineries, petrochemical plants and energy facilities operated within a 25km (15.5-mile) radius of the First Nation, according to a recent report by environmental group Ecojustice. That figure included 23 facilities that emitted more than 50 tonnes of air pollutant per year. In total, Sarnia-area facilities emitted more than 45,300 tonnes of air pollutant that year - about 10 percent of total emissions across the province of Ontario. Chemical Valley accounts for about 40 percent of Canada’s chemical industry.