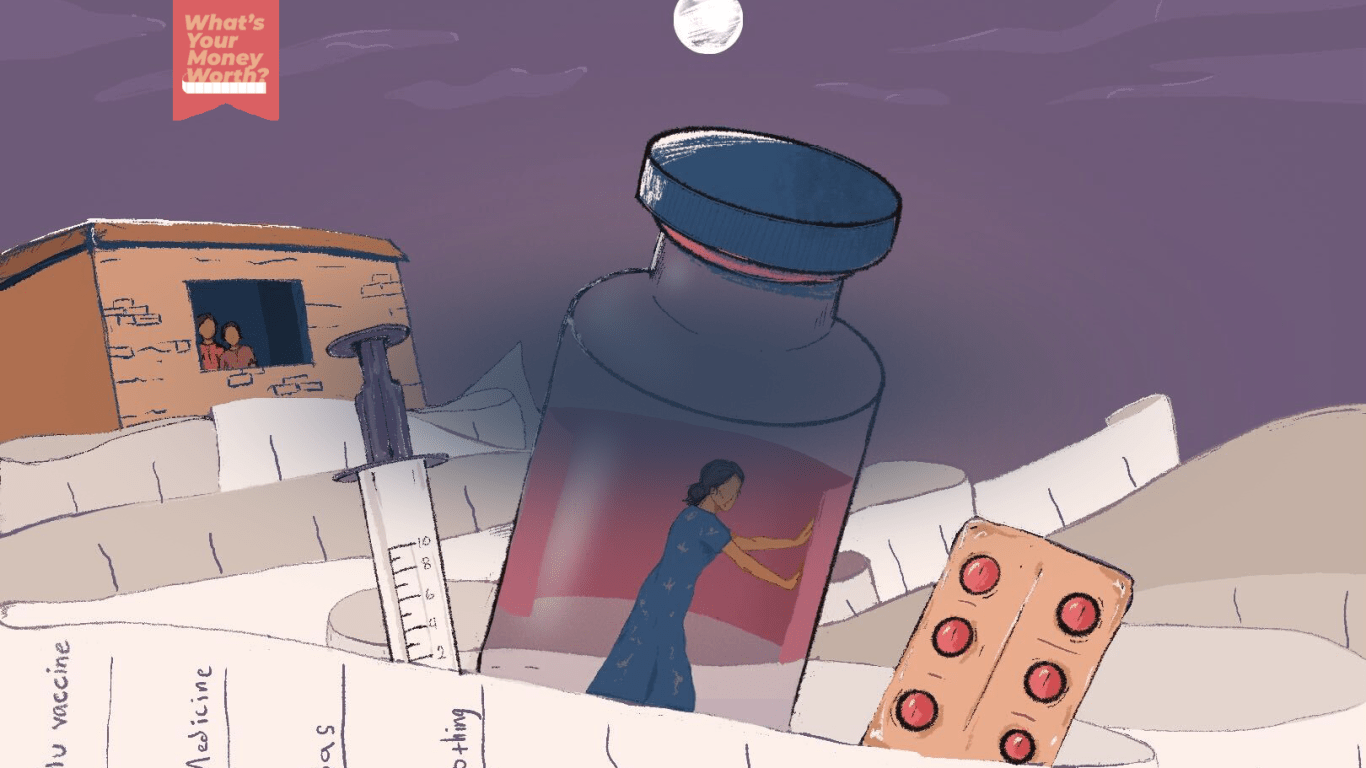

‘I can’t afford my medicine'

How a domestic worker and grandmother taking care of two children manages her monthly budget.

What’s your money worth? A series from the front line of the cost-of-living crisis, where people who have been hit hard share their monthly expenses.

Name: Jacintha Fonseka

Age: 55

Occupation: Domestic worker

Lives with: Husband Nishantha Garusinghe, 51, and granddaughters Thisuni Dinethma, 11, and Dimagi Hithmini, seven

Lives in: A 26.8sq-metre (289.3sq-foot) house in Kelaniya, a mostly working-class suburb of Sri Lanka’s executive and judicial capital, Colombo.

Monthly household income: 33,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($89.34). The minimum monthly income needed by a family in the district where they live is $162, according to Sri Lanka’s Department of Census and Statistics.

Total expenses for the month: 32,700 rupees ($88.53)