In Pictures

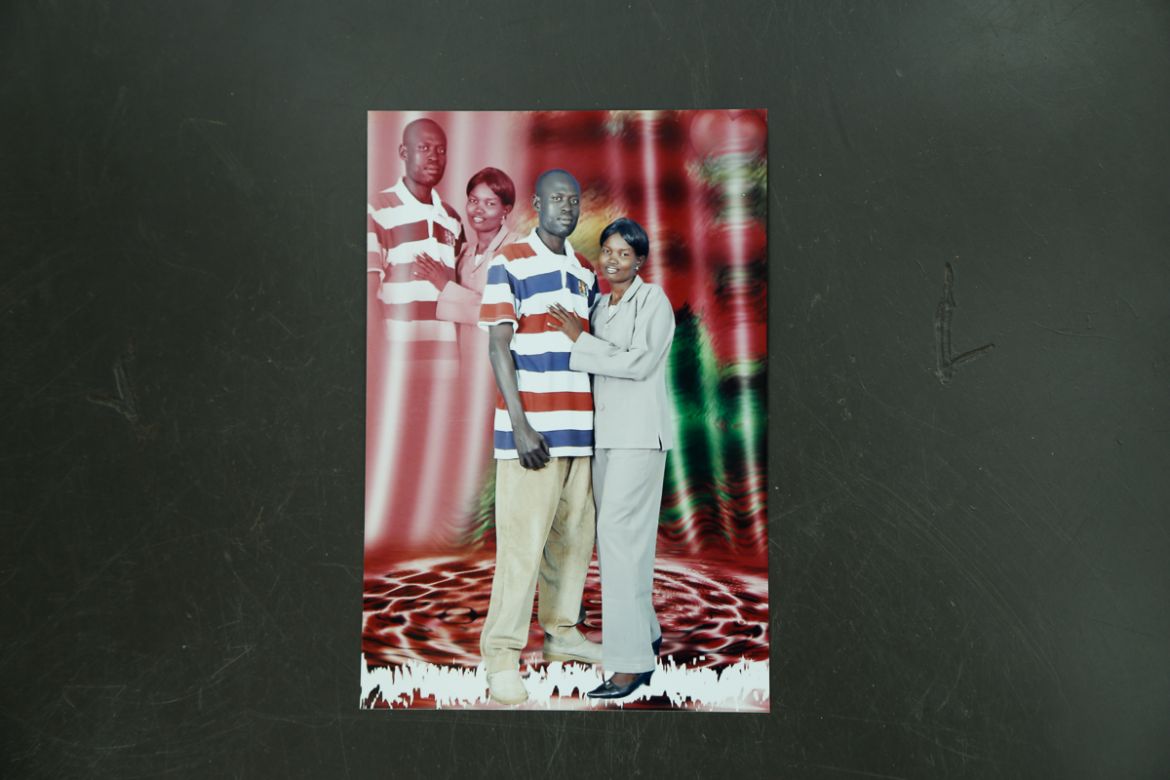

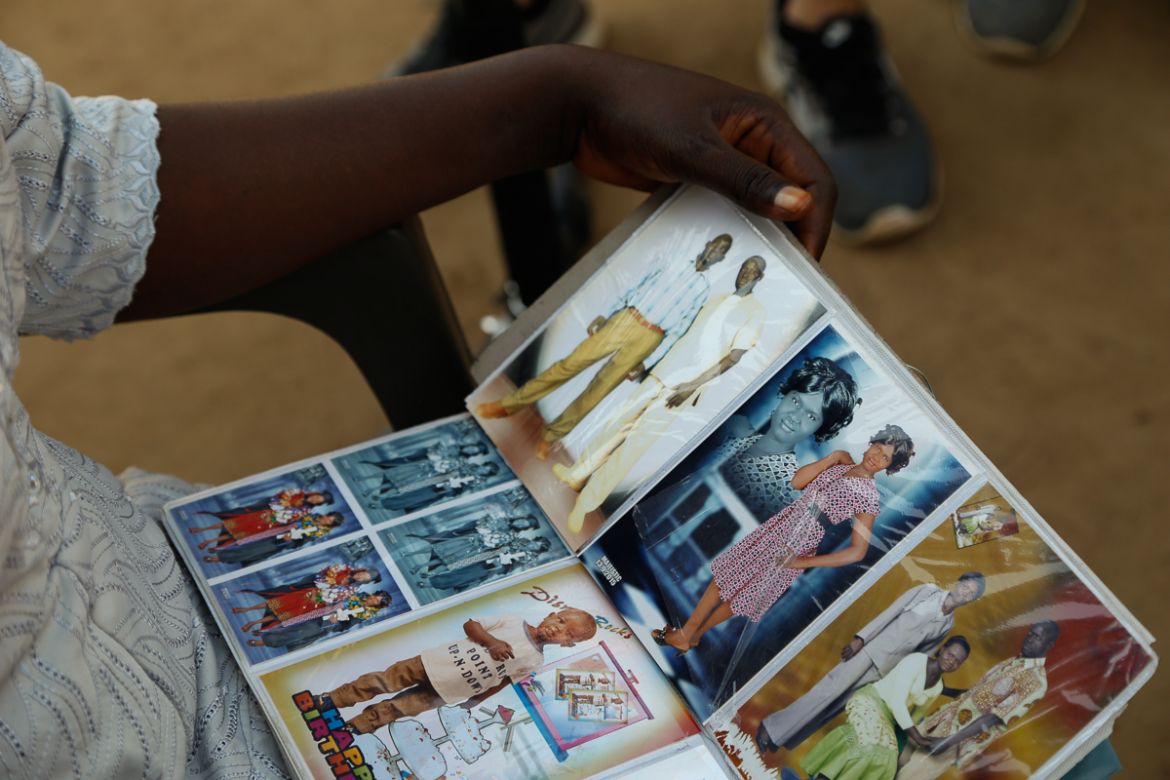

Healing trauma in South Sudan through mental health programmes

Trauma caused by years of conflict remain largely untreated with lack of mental care in South Sudan.

“We define trauma as a wound. It is when something shocking or abnormal happens in your life, and it overwhelms you and you don’t know how to respond,” says Thor Riek, a 32-year-old South Sudanese.

South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, achieved independence in 2011 after decades of fighting. The country has spent most of its short existence embroiled in conflict, after an internal armed struggle escalated into a civil war in December 2013 that continues until present day.

The civil war has displaced at least 4.5 million, or one in three, South Sudanese from their homes. Estimates of the death toll range from 50,000 civilians to as many as 383,000, according to a new report by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The civil war has exacerbated a long-standing legacy of psychological distress and mental health issues left behind by decades of conflict.

While official national statistics on mental health are not available, different studies have shown that the conflict has had a severe effect on the mental wellness of civilians.

Almost 41 percent of 1,525 respondents showed symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a 2015 study carried out by the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Mental health resources are badly lacking in South Sudan, with as few as two practising psychiatrists available in the whole country as of 2016, according to Amnesty International.

Many South Sudanese with psychological distress and trauma rely on workshops and programmes organised by NGOs such as USAID and World Vision, or a local church or community groups.

“Trauma that is not healed is transferred,” says Thor, who grappled with trauma from his days as a child soldier in the 1990s. Now, he is a trainer for VISTAS (Viable Support to Transition and Stability), a programme funded by USAID, that holds workshops and initiatives to provide communities with practical tools to address trauma and the possibility of reconciliation.

With the workshops, Thor hopes that it will help participants “to have a narrative that can move them forward from the cycle of violence and begin to walk on the healing journey.”

We Shall Have Peace, the recent VR documentary produced by Al Jazeera’s Contrast media studio, explores South Sudan through the lens of trauma and healing. Watch how three South Sudanese are working for a better future by confronting their pasts.