‘Blunt, unplanned’: Police tactics under fire in HK protests

Amid increasingly violent unrest, experts say trust in force is being undermined and will be hard to rebuild.

Hong Kong, China – Hong Kong police have deployed tear gas, rubber bullets, bean bag rounds and live ammunition since protests began in June, but amid increasingly violent clashes, there is concern that recent changes to policing guidance will only aggravate the situation.

Internal police documents obtained by legislators and seen by Al Jazeera show that since September, the Hong Kong police force has lowered its threshold for the use of force.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘We won’t give up’: Hong Kong protesters defiant after shooting

China slams ‘terrorist-like actions’ by Hong Kong protesters

“Originally, they needed to at least evaluate whether the opponent or the protesters or the other side intended to use which level of force, now it is ‘likely’ to cause, so it seems its easier for them to prove that the use of force is proportionate to the level of resistance,” said pro-democracy legislator Tanya Chan, who is familiar with the changes.

Chan said she was also concerned about the removal of a key phrase that said “officers would be accountable for their own actions” in a section outlining appropriate use of force.

“This deleted sentence reminded police officers that they may have a personal duty or obligation; [that] they need to be accountable for their own actions. But now it’s totally deleted.”

Once considered one of the region’s most respected police forces, the protests have turned the Hong Kong police into one of the territory’s most controversial institutions, undoing decades of work to secure public trust.

Experts say the problems started almost as soon the demonstrations began, when protesters surrounded the Hong Kong legislature just days after one million people marched through the streets demanding the withdrawal of a controversial extradition bill.

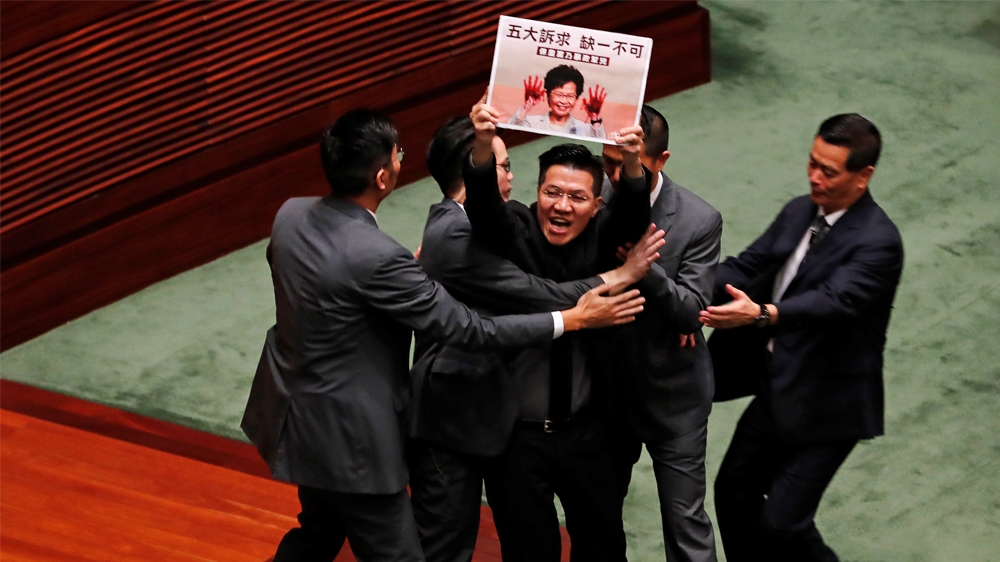

The crowds were worried the territory’s leader, Carrie Lam, would try to push the bill through despite the scale of public opposition.

“Our analysis that June 12 was the first escalation of force and what we’ve seen is a spiralling escalation based on that,” said Robert Godden, cofounder of the human rights consultancy Rights Exposure, which sends observers to the Hong Kong protests each week.

‘Hostile measures’

While protesters were clearly angry, police responded with what appeared to the crowd to be hostile measures, including firing tear gas, rather than de-escalate the tension.

They also failed to distinguish between the majority of protesters who were peaceful and those who felt compelled to fight back, Godden said.

“It’s poor management, strategy and planning that partly got us here in the first place and continues to feed this cycle of violence,” he added.

“It’s very indiscriminate, very blunt, very unplanned, very unsophisticated policing.”

Immediate outrage prompted two million people to return to the streets several days later, but trust eroded further and civil unrest continued as the government failed to respond.

|

|

As weeks became months of protest, many residents began to wonder whether the police were really there to protect them, after tactical blunders saw officers fire tear gas and pepper spray inside metro stations and train carriages.

Bystanders also appeared to be targeted as well during protests, with little distinction made between the different kinds of peaceful and violent protesters.

Then, shortly after revisions to the riot manual were put in place, a police officer shot a teenager in the chest at an October 1 demonstration after a group of protesters attacked another officer.

The 18-year-old, who appeared to be armed with a PVC pipe, was later charged with rioting and assaulting a police officer. The shooting itself will be investigated internally according to police procedures.

A week after that, an off-duty police officer shot a 14-year-old after he was attacked by a group of protesters.

Pepper sprays and batons

Following the incident, police were given permission to carry pepper spray while off duty in addition to batons, according to public broadcaster RTHK.

The Hong Kong police declined to respond to specific questions from Al Jazeera over their approach to the protests.

In previous statements, however, they have said their crowd dispersal operations are necessary to deal with violent protesters who pose a serious threat to public order.

The government has also given its full support to the police, saying this week that officers had exercised “restraint” and continued to carry out enforcement actions “in strict accordance with the law” during protests.

It further said that police actions were intended to “bring offenders to justice and restore public order as soon as possible.”

The police response to the 2019 protests contrasts sharply with the past and Hong Kong was considered a model for others to emulate including the Metropolitan Police in London and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

In decades past, the police manual called for tear gas to be fired as a weapon of last resort and in a way that allowed protests to leave through pre-arranged avenues, according to Carol Jones, who has taught courses on criminology in Hong Kong and also researched the Chinese criminal justice system.

New police tactic

In recent months, however, the police appear to be using tear gas indiscriminately while also firing rubber bullets and other non-lethal force methods at close range, Jones said.

“These tactics are not tactics the Hong Kong police are historically known for,” she said. “It’s really a new departure that they use things as offensive weapons rather than as defensive against crowds.”

The riot manual also calls for the force to take a more paramilitary approach during unrest – a partial legacy of the deadly 1967 communist riots – but such tactics can only ever be temporary, said Martin Purbrick, a former member of the colonial police whose analysis of this year’s unrest was published in Asian Affairs in October.

Taking such a forceful approach for too long risks undermining public support for the police, he warned.

With the Hong Kong government’s failure to find a political solution to the protests – constrained in part by Beijing – that is precisely what has happened as demonstrations have failed to end for 21 straight weeks.

As officers have removed ID tags from their uniforms, police and their families have become targets of social media doxing by some protesters.

Public turns against police

Much of the general public also seems to have turned against them, with even peaceful protesters and bystanders shouting obscenities as they pass by groups of officers or police headquarters on demonstration days.

|

|

“The Hong Kong police moved from a situation of widespread public acceptance and support to one of public distrust and even hatred,” Purbrick said. “This is a crisis of legitimacy for the police.”

Police have arrested more than 2,700 people and charged 445 with a variety of crimes, including unlawful assembly and assaulting a police officer since June.

Among that group, 223 have been charged with rioting, according to an arrest spreadsheet maintained by activists.

Rioting is a common-law offence in Hong Kong that can carry a jail term of as long as 10 years and revoking that charge, as well as setting up an independent investigation into police brutality, have become a key protest demand.

Even some pro-China legislators, including Michael Tien and Abraham Shek, have backed an independent inquiry, but it has been blocked by police unions.

Instead, the government has offered a review by the Independent Police Complaints Council.

Amid so much distrust, experts say it will be hard for the police to rebuild respect.

While the protest movement may eventually die down, it has revealed deep fault lines in Hong Kong society and ongoing questions about the nature of the structure of the local government and its relationship with China.

Lawrence Ho Ka-ki, a specialist in criminal justice, policing and public order management at the Education University of Hong Kong, said respect for the police was based on the perception that their duties were broadly apolitical and focussed on crime.

But as Hong Kong faces its worst political crisis since the 1997 handover, and the force has been thrust onto the front line, it will be hard for the police – and the city – to recover.

“This is totally political,” Ho said. “In the past, it was really issue-based. Once it turns to some sort of really abstract struggle on whether the police are fair, whether they are representing the government, what are they serving for – I think this is really, really conceptual and not easy to solve.”