Vietnam fights China’s ‘nine-dash line’ amid old enmities

Vietnam is pushing back on Chinese claims over the South China Sea targeting Beijing’s controversial nine-dash line.

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam – It came as no surprise to Vietnamese student Doan Thanh Hai that China’s infamous nine-dash line has been causing trouble in his country.

China has long used the geographical demarcation to claim an historical connection to much of the resource-rich South China Sea, including large areas that are claimed also by Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMarcos Jr treads fine line with China as Philippines deepens US, Japan ties

Japan, Philippines, US rebuke China over ‘dangerous’ South China Sea moves

Biden, Japan leader Kishida announce stronger defence ties in state visit

The law student at the University of Economics and Law in Saigon has been reading up on China’s tactics, watching as China has tried to push its controversial map, also known as the “cow tongue” for its shape, into Vietnam over the past few years.

“I think the majority of Vietnamese people are strongly aware of our sovereignty and to change our stand on this is definitely not easy,”Hai told Al Jazeera. “But, realistically speaking, images of the cow tongue are threatening our sovereignty in many ways.”

While the two Communist-ruled countries have much in common, they have a long history of resentments reaching back to China’s colonisation of parts of northern Vietnam centuries ago.

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2017, the most recent available, found 92 percent of Vietnamese viewed Chinese power and influence as a threat to their country.

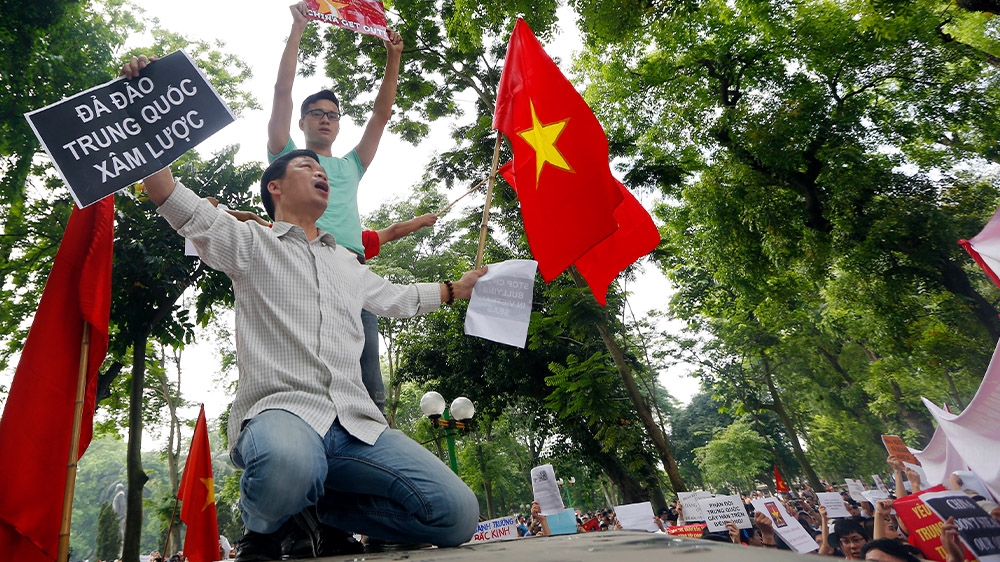

Anti-China protests

There were anti-China protests throughout Vietnam last year, sparked by fears that a new government policy allowing foreigners to lease land in three special economic zones would be dominated by Chinese investors.

Previous years also saw protests over China.

The China relationship is one of the few areas where the government gives people a little more space for comment in a society that is tightly controlled. Vietnam ranks 176th of the 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ 2019 World Press Freedom Index, one spot above China.

“The Communist Party leadership has demonstrated that it is willing to allow the people to express some frustration with China to avoid anger from building up over time that might threaten national stability and Party control,” Derek Grossman, a senior defence analyst at the RAND Corporation, told Al Jazeera.

In February, in an unprecedented move, the government-controlled Vietnamese media referred to China in relation to the 40th anniversary of the China-Vietnam border war as the “invader”, and the conflict as a “war”.

It is an approach that helps Vietnam meet its foreign policy objectives.

“Domestic criticism of China, and just the use of the word ‘China’ in historical discussions, signals to Beijing that Vietnam is dissatisfied,” Grossman said. “Though subtle to the outside observer, Beijing understands this signalling and may or may not respond to Vietnamese concerns.”

|

|

Now Vietnam has the “nine-dash line” in its sights.

Cars, films, celebrities

The 2,000 kilometre (1,242 mile) U-shaped line first appeared in maps of revolutionary China in the 1940s, but an international tribunal brought the Philippines ruled in 2016 that there was “no legal basis” for China’s claims.

Over the past couple of months, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade has told importers to closely inspect and reject any goods that contain the map, after a domestic importer was found selling Chinese-made cars that had the nine-dash line in the default navigation system.

Vietnam’s automobile registrar ordered the importer to remove the map and said it would refuse to certify any goods that included the nine-dash line, according to an announcement published on the website of Vietnam’s General Department of Customs.

It also fined Volkswagen’s local distributor after a 2020 model Touareg imported from China and displayed at a motor show in Ho Chi Minh City was found to have the nine-dash line map on its navigation app.

It is not only cars have fallen foul of the crackdown.

The DreamWorks animated film Abominable, which was released in Vietnam in October, was pulled after viewers spotted the map in a scene. The Acting Director of the Cinema Department Nguyen Thi Thu Ha was demoted for allowing the film to be screened, state media reported.

And celebrities who appear to support China’s maritime claims have found they are not welcome either.

Earlier this month, Operation Smile Vietnam (OVS)’s Facebook page was deluged with comments condemning Jackie Chan’s alleged endorsement of the controversial map, prompting the Hong Kong star to cancel his humanitarian trip to Vietnam.Chan has been an ambassador of the medical charity, which helps children with facial deformities, since 1994.

The boycott is taking place amid a months-long standoff between Vietnamese ships and a Chinese survey fleet over Vanguard Bank. The resource-rich area is about 160 nautical miles (296km) from the southern beach of Vietnam’s Vung Tau and about 600 nautical miles (1,111km) from China’s Hainan Island.

The US issued a stern warningcondemningChina’s “bullying behaviour” that same month, and on his visit in November Defense Secretary Mark Esper said that the United States had decided to give Vietnam a second Coast Guard cutter to allow more marine patrols.

#MoFASpoz updates on #HaiyangDizhi8:

➡️The ship continues to infringe #VietNam’s sovereignty, sovereign rights, EEZ & continental shelf.

🗣️🗣️🗣️Viet Nam demands #China to IMMEDIATELY STOP its serious violations and WITHDRAW all of the vessels from Vietnamese waters#SouthChinaSea pic.twitter.com/qeGrEauOHb— MoFAVietNam Spokesperson (@PressDept_MoFA) September 13, 2019

During the heated standoff, Vietnamese President Nguyen Phu Trong said Vietnam should “never compromise” on its sovereignty and territorial integrity while Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe insisted China would “not allow even an inch of territory that our ancestors have left to us to be taken away.”

“It’s doubtful that [Vietnam’s efforts] will have much impact on China, which appears hellbent on impressing upon Vietnam and the other disputing countries that the South China Sea is China’s, as are the hydrocarbons and fish in the sea,” said Murray Hiebert, an expert in US-Vietnamese relations at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington.

The lack of global political will to isolate or sanction Beijing will make it difficult for Hanoi to marshall much diplomatic pressure against China, he added.

|

|

“Vietnam has sought to drum up support in ASEAN and in friendly countries like Japan, Australia, and the EU, but only the US has been willing to criticise China for its harassment of the Rosneft oil rig off Vanguard Bank. The others appeared afraid that China would punish them.”

The maritime dispute has previously overshadowed ASEAN or Association of Southeast Asian Nations summits. Vietnam will be chair in 2020 and has been trying to conclude a “code of conduct” with China over the South China Sea.

At a lecture this week at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Deputy Foreign Minister Nguyen Quoc Dung said he hoped China would “show restraint” over the disputed waters.

Hai, the university student from Saigon, does not think Vietnamese students like him are susceptible to China’s propaganda.

But he is concerned that China’s claims might influence a global viewpoint, which might eventually have an impact on Vietnamese minds.

“China’s consistently incorrect claims might be accepted by a large pool of people around the world. Through different channels and forums, this community might influence Vietnamese young people’s understanding of the region.

“So it is important that we fire back at their fraudulent claims and assert Vietnamese sovereignty both in and outside of Vietnam,” Hai said.