Satellite images show ongoing destruction of Rohingya settlements

Analysis shows ‘minimal preparation’ for return of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar’s northern Rakhine State.

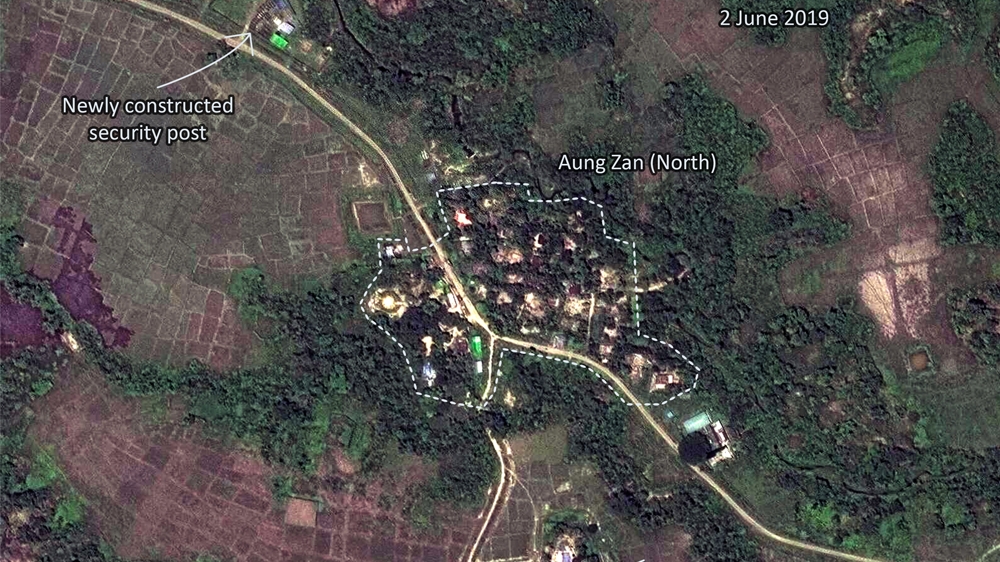

Aung Zan village in Myanmar‘s northern Rakhine State lies just a few kilometres from the Bangladesh border.

Once home to a small community of Rohingya, its 50 buildings were almost entirely burned down during violent crackdowns that forced more than 745,000 refugees into Bangladesh in 2017.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsConflict, climate, corruption drive Southeast Asia people trafficking: UN

Bodies of three Rohingya found as Indonesia ends rescue for capsized boat

How is renewed violence in Myanmar affecting the Rohingya?

New satellite analysis released on Wednesday by an Australian think-tank, the International Cyber Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), shows “minimal preparation” for the return of Rohingya refugees amid the continuing destruction of residential areas and an increase in military facilities in northern Rakhine.

In Aung Zan village, ASPI says the last remaining residential structures were demolished in the first three months of 2019, while security posts there were expanded and fortified.

These trends apply to 392 Rohingya settlements, where satellite images gathered by the centre between December 2018 and June 2019 indicate that 40 percent of the villages originally identified by the United Nations’ satelite tracking service UNOSAT as burned, damaged or destroyed during the 2017 crisis have since been entirely razed, with an additional 58 villages the target of new demolition.

In their place, 45 camps have been extended throughout the state where six suspected military facilities also appear to have been built featuring a combination of defensive trench positions, helipads and guarded entrances.

Elaine Pearson, the Australia Director at Human Rights Watch, says ASPI’s findings align with their own documentation of the Myanmar authorities’ active acquisition of razed land in northern Rakhine.

“Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh have been able to show us documentation of their ownership of houses and land they lived in before having to flee in August 2017,” she said. “Where refugees say their homes once stood, there is visible construction of government-like buildings over razed or burned land.”

|

|

According to ASPI, the developments captured by satellite imagery cast doubt on the credibility of claims that refugees will be allowed to return to their homes and raise concerns about the conditions under which those who return would be expected to live.

“The continued destruction of residential areas across 2018 and 2019 – clearly identifiable through our longitudinal satellite analysis – raises serious questions about the willingness of the Myanmar government to facilitate a safe and dignified repatriation process,” said Nathan Ruser, a researcher with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre in a statement.

“The ongoing violence, instability, disruptions to internet and communications technologies and the lack of information about the security situation in Rakhine add to those concerns,” the study found.

The findings come in the wake of a leaked ASEAN report penned by the Emergency Response and Assessment Team (ASEAN-ERAT) that gave a two-year trajectory for the completion of voluntary returns of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar.

The report was met by outcries from experts and activists for its focus on the Myanmar government’s infrastructural preparedness rather than human rights concerns.

“Given the current situation and context in Rakhine, the lack of redress for victims, the lack of access to services and livelihoods in the areas where housing infrastructure is planned, there is no evidence to show the repatriation process can take place within two years,” Pearson wrote via email.

Among the infrastructure highlighted by the ASEAN-ERAT report, the Taung Pyo Letwe reception centre is a 10,000 square metre facility set to cover administrative processes for 300 refugees per day.

But ASPI’s cyber centre says it appears more akin to a detention centre featuring housing areas surrounded by fences and watchtowers.

John Quinley III, Human Rights Specialist at Fortify Rights told Al Jazeera that the “so-called reception centres look more like prisons” and could further the apartheid system in place in other parts of the state.

“Many Rohingya refugees we have spoken with in Bangladesh say they will not return until they can go back to their original homelands,” said Quinley.

For the Rohingya in Kutapalong refugee camp in Bangladesh, the new satellite analysis casts a shadow of doubt on their hopes of one day returning to their homes.

“They broke down our house, but they did not burn it, said 37-year old Abdu Ruhim proudly holding up a photo of the wooden house his family had just moved into in Buthidaung Township when violence broke out in 2017, “at least not the first time.”

“If they give my relatives living in camps in Sittwe citizenship then I will think about going back,” says the father of three. “But I won’t take my children back to live in a camp.”