Understanding the Wet’suwet’en struggle in Canada

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief, gov’t announce proposed deal in dispute that raised key questions on Aboriginal title.

Montreal, Canada – Mass demonstrations, sit-ins and blockades have gripped parts of Canada over the last month as a movement to support the leaders of an Indigenous nation who are opposed to a multibillion-dollar pipeline project in northern British Columbia (BC) grows.

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have come out against the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which seeks to transport liquefied natural gas from northeast BC to a terminal on the coast near the town of Kitimat.

Keep reading

list of 2 itemsA year after RCMP’s violent raid, Wet’suwet’en people fear repeat

The 670-kilometre (417-mile) pipeline will cut across traditional Wet’suwet’en lands that cover 22,000sq km across northern BC.

The hereditary chiefs, who under Wet’suwet’en law claim authority over those traditional territories, said they never gave their consent for the project to move forward. They have raised concerns about the pipeline’s potential effects on the land, water, and their community.

On Sunday, a Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief and government ministers said they reached a proposed arrangement on how to move forward. The details of the agreement will not be released until they have been presented to the Wet’suwet’en people.

While Sunday’s agreement represents an important step in a conflict that has gripped much of Canada, the struggle of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs raised important questions of Aboriginal title, land ownership and consultation with First Nations.

“I think it would be a mistake to understand what’s happening right now as just about a natural gas pipeline,” said Eugene Kung, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law in Vancouver, before the agreement was announced.

“There are much deeper, underlying issues that remain unresolved and that I think are at the root of this,” Kung told Al Jazeera.

Aboriginal title

Key among those underlying issues is the fact that the Wet’suwet’en Nation’s claim to their ancestral lands, through which the pipeline will be built, remains unresolved.

Aboriginal title refers to the inherent right of Indigenous peoples to use and occupy the lands they occupied for thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers. Aboriginal title was “recognised and affirmed” in the Canadian constitution in 1982, and the courts have laid out the test for Indigenous nations to prove their title claims.

In a 2014 case, Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada explained that Aboriginal title flows from the sufficient, continuous and exclusive “occupation” of the land. That can include Indigenous culture and practices, such as hunting or fishing. “Where Aboriginal title has been established, the Crown must not only comply with its procedural duties, but must also justify any incursions on Aboriginal title lands,” the court wrote.

In 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada was asked to determine Aboriginal title in a case involving the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan nations, Delgamuukw v. British Columbia.

The court found that the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs were the rightful holders of title to their unceded territories and recognised that the community’s Aboriginal title had not been extinguished, explained Robert Hamilton, assistant professor at University of Calgary Faculty of Law.

But “for procedural reasons [the Supreme Court] sent the case back to trial” and it was not picked up again, Hamilton told Al Jazeera in a phone interview before Sunday’s announcement.

He said the court signalled to the federal and provincial governments that Aboriginal title remains an outstanding issue that must be resolved. “‘Here’s the test that we’re going to use in determining where Aboriginal title exists … so, you had best get on with the business of negotiating with these parties that have outstanding Aboriginal title claims,'” Hamilton said, about what the court said in Delgamuukw.

The Wet’suwet’en title claim was never resolved, however.

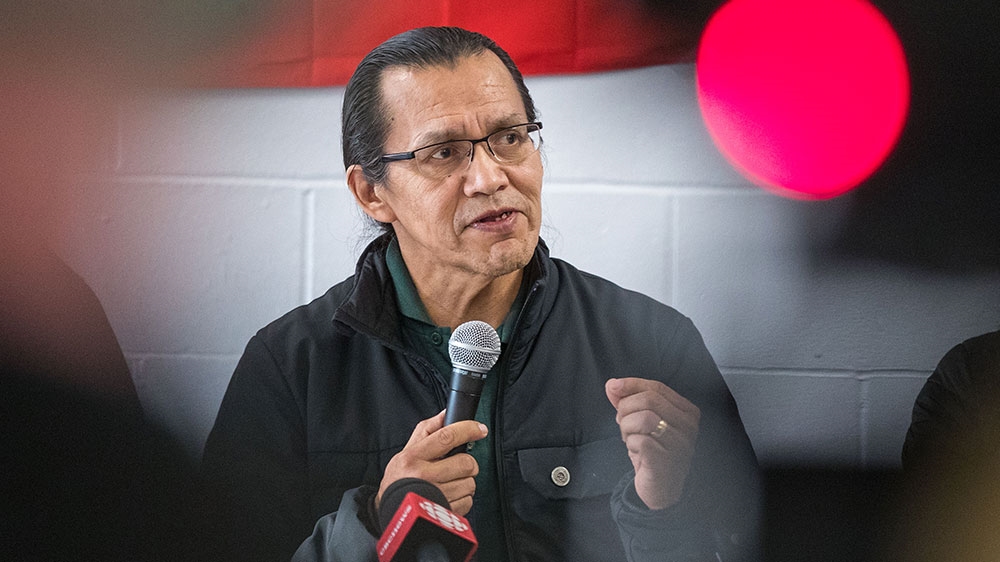

On Sunday, Wet’suwet’en Chief Woos, who also goes by the name Frank Alec, said the proposed agreement with the government picks up where Delgamuukw left off.

“What we were always here to do is to protect our yintah [land] … We say to all the developers out there, our pristine waters, our headwaters, our wildlife habitats, our traditional sites … we are going to protect it,” Chief Woos said during a news conference.

It is still unclear what was decided, however, and details of the proposed deal are expected to be presented to the Wet’suwet’en people over the next two weeks.

“While we have disagreement on this issue, we are developing a protocol … to recognise rights and title for the future,” BC Indigenous Relations Minister Scott Fraser said on Sunday in a news conference alongside Chief Woos. “I ask for some space and calm to allow us to continue that work.”

Consultation and accommodation

When Aboriginal title is asserted, as in the case of the Wet’suwet’en, the government holds a duty to consult and accommodate the community when their rights may be infringed by a government decision, such as a resource extraction or development project.

That is a lower standard than when Aboriginal title is established under Canadian law, said Hamilton, as in the Tsilhqot’in Nation case.

The level of consultation and accommodation must be proportional to the potential adverse effects of a decision, or to the strength of the assertion of Aboriginal title, the Supreme Court said in a 2004 decision involving the Haida Nation, also in BC. “The Crown is not under a duty to reach an agreement; rather, the commitment is to a meaningful process of consultation in good faith,” the court said then.

Governments often outsource the consultation process to third parties, such as the Canada Energy Regulator (formerly known as the National Energy Board). But consultation must be carried out in good faith and what is known as the “honour of the Crown” must be upheld.

The process is flawed, however, because the government is “aiming for the floor” – in other words, it works to meet the minimum standard required, Kung told Al Jazeera. He said the consultation framework was also meant to be temporary until underlying land issues can be resolved, but it is instead “treated as an indefinite norm and as the end of the line in terms of obligations”.

“Obviously, that approach is not working,” Kung said.

Who is consulted?

The groups that are consulted often also become a matter of contention.

In its 1997 ruling, the Supreme Court of Canada recognised that the rightful Wet’suwet’en titleholders were the hereditary chiefs.

The nation is divided into 13 houses and five clans: Gilseyhu, Tsayu, Laksamshu, Gidimt’en and Laksilyu. Under Wet’suwet’en law (Anuk nu’at’en), the traditional territory is divided between the houses and clans, and the hereditary chiefs hold authority over their respective areas.

But the federal and provincial governments have “maintained a policy of denying the Wet’suwet’en title to the land for decades”, said Bruce McIvor, principal at First Peoples Law who represents the Unist’ot’en, a house group of the Wet’suwet’en Nation.

“As long as they maintain the position of denial, they’re in a stronger position to force through major resource extraction projects, such as pipelines or open-pit mines or hydro dams. The legal obligations on them are significantly lower,” McIvor told Al Jazeera.

Meanwhile, TC Energy said it “has the utmost respect” for the Indigenous systems of governance in BC and “strived to engage with all the Indigenous groups along the pipeline route”. It said it has engaged in “a wide range of consultation activities” with the hereditary chiefs, including 120 in-person meetings.

The company also said it reached agreements with 20 First Nation bands along the project route, including five Wet’suwet’en bands. Those deals “were developed over many years through collaborative engagement”, it said on its website.

Indian Act chief and councils

The First Nations band council and chief system were created by the Indian Act of 1876, the federal law under which the government regulates and manages the lives of First Nations. The act gives the councils and chiefs, who are elected by First Nations band members, the power to administer the day-to-day running of reserves, the First Nations communities that also were created by the Indian Act.

McIvor said while some First Nations have been able to work through the chief and council system with the support of their members, in the case of the Wet’suwet’en “no one really thought that you can simply go speak to the Indian Act chief and councils”.

The rightful titleholders are the hereditary chiefs, he said, and “to say otherwise is either willful ignorance or simple intention to encourage disagreement”.

It is not clear how many Wet’suwet’en people on an individual level support the Coastal GasLink project or how many are against it. Some have publicly expressed support for the project, some have shown reticent support, and others are strongly opposed.

In the BC Supreme Court decision in late December to issue an injunction allowing construction to continue on the pipeline, Justice Marguerite Church stated that “the Indigenous legal perspective, in this case, is complex and diverse”.

Church also said “the Wet’suwet’en people are deeply divided” over the project.

McIvor said it is understandable that some Indian Act band councils and chiefs would sign on to the project, as communities are impoverished and have been unable to benefit from projects in their territories. “Unfortunately, this is ripe for companies and for [the] government to take advantage of,” he said.

Beyond Canada

Beyond Canadian law, Indigenous rights are also enshrined in international legal frameworks, notably the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). While Canada initially opposed the declaration, it has since signed on and pledged to incorporate it into its national laws. To date, BC is the only place in Canada to pass legislation that aims to get its laws in line with UNDRIP.

That move was welcomed in November as a key step on the path to reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and the government. But at the height of the standoff on Wet’suwet’en lands, BC Premier Horgan said the legislation was not retroactive and would not apply to the Coastal GasLink project.

“We want everyone to understand that there are agreements from the Peace Country to Kitimat with Indigenous communities that want to see economic activity and prosperity take place,” he said on January 13. “This project is proceeding and the rule of law needs to prevail in BC.”

Brenda Gunn, associate professor at the University of Manitoba faculty of law, explained that UNDRIP lays out the government’s obligation to obtain Indigenous peoples’ “free, prior and informed consent” if their rights will be affected by a decision.

“One of the key aspects of free, prior and informed consent is the notion of ‘free’ – and this means without coercion and it also means the right to participate according to their own government institutions and determine for themselves who represents them,” Gunn told Al Jazeera.

She said “free” also means people should not seek to divide and conquer Indigenous peoples, or in the case of the Wet’suwet’en, not pit the hereditary chiefs against the band councillors, chiefs or anyone else who supports the Coastal GasLink project.

“Free, prior and informed consent includes the ability to give or withhold consent. You don’t effectively have consent in law if you’re not allowed to say no,” Dunn said.

On Sunday, Canada’s minister of Crown-Indigenous relations, Carolyn Bennett, said major projects need to be put before an Indigenous nation as outlined by UNDRIP.

“It means that at the very first idea of a project, that the rights holders would be there at the table with their Indigenous knowledge and the voices of their nation,” she said during the news conference alongside Chief Woos.

What’s next?

The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs have repeatedly laid out their demands: withdraw federal police (RCMP) officers from their traditional territory and order Coastal GasLink to suspend construction while nation-to-nation discussions with the government are continuing.

It is unclear which, if any, demands are part of Sunday’s proposed agreement, and what the future of the pipeline may be.

Wet’suwet’en land defenders have set up camps and checkpoints to reclaim their traditional territories in the area slated for pipeline construction and stop the project from moving ahead. They have also insisted that the RCMP leave the area and for Coastal GasLink to stop building – and it is unclear what Sunday’s proposed agreement may mean for them.

In January, RCMP officers removed dozens of Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their supporters from the camps along the pipeline route to allow the company to continue with construction activities.

“Obviously, [the RCMP is] not out there to protect the Wet’suwet’en people; they’re out there to protect the CGL employees. We need to correct that,” Wet’suwet’en Chief Woos said on Sunday.

After three days and nights of talks NO agreement on Coastal GasLink has been reached. However, a tentative agreement has been reached on Wet’suwet’en rights and title. This will not be publicly released until Wet’suwet’en people have a chance to review over the next few weeks. pic.twitter.com/2Zevt7FNmP

— Gidimt’en Checkpoint (@Gidimten) March 1, 2020

Late last month, the BC Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) said it could not issue a final certificate authorising construction on the pipeline through a section of Wet’suwet’en territory until Coastal GasLink went back to negotiate with the leadership about some outstanding potential effects. The office said concerns about the project’s effects on a Wet’suwet’en healing centre still needed to be addressed. It gave Coastal GasLink 30 days to conduct more consultations and provide an updated assessment.

“It is very distressing, after we’ve faced assault rifles and endured arrests at the beckoning of CGL, to now be advised by EAO to work collaboratively with them to address these gaps,” Karla Tait, a Unist’ot’en house member and volunteer director at the Unist’ot’en healing centre, said in a statement.

In a statement, Coastal GasLink president said construction that was paused for talks between the Wet’suwet’en chiefs and the government will resume on Monday.

“While much has been accomplished, much work remains and we wish all parties success as their work continues and the Wet’suwet’en people consider the proposed arrangement,” David Pfeiffer said.

It was also unclear whether Sunday’s proposed agreement addressed the presence of the RCMP in Wet’suwet’en traditional territories.

Still, Chief Woos told reporters Sunday’s announcement represented “quite a milestone for all of us to view this together”.

“We’re at a point, in this moment in time, to see if the arrangements will work in all aspects of what we stand for as Wet’suwet’en,” he said.