Blockades test main forces in Bolivia amid election crisis

A cautious calm has now taken hold after the electoral tribunal decided to hold presidential elections on October 18.

Black remnants of scorched tires still stained dozens of Bolivia’s main streets on Monday, after nearly two weeks of marches and road blockades by protesters furious with the government’s decision to delay the presidential rerun election once more, amid the country’s worsening coronavirus outbreak.

Thousands of protesters allied with the former leftist president Evo Morales had set up nearly 150 roadblocks nationwide demanding elections be held on September 6 – paralysing the Andean nation, causing food shortages and delaying the transport of critical medical supplies.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

A cautious calm has now taken hold, and on Monday, markets were slowly being restocked after Bolivia’s electoral tribunal last week enacted a law that mandated a presidential election must be held on October 18, citing the need to avoid a September projected peak in COVID-19 infections.

“After two weeks of violent protests and roadblocks, the country is now recuperating its sense of normalcy, after guarantees that elections can be held on October 18,” said Raul Penaranda, a journalist and political analyst based in La Paz.

“There is a feeling that the elections can be a possible solution to the problems of instability in the country,” Penaranda told Al Jazeera.

The United Nations, the European Union, and the Catholic Church mediated the talks between the government and leaders of social movements.

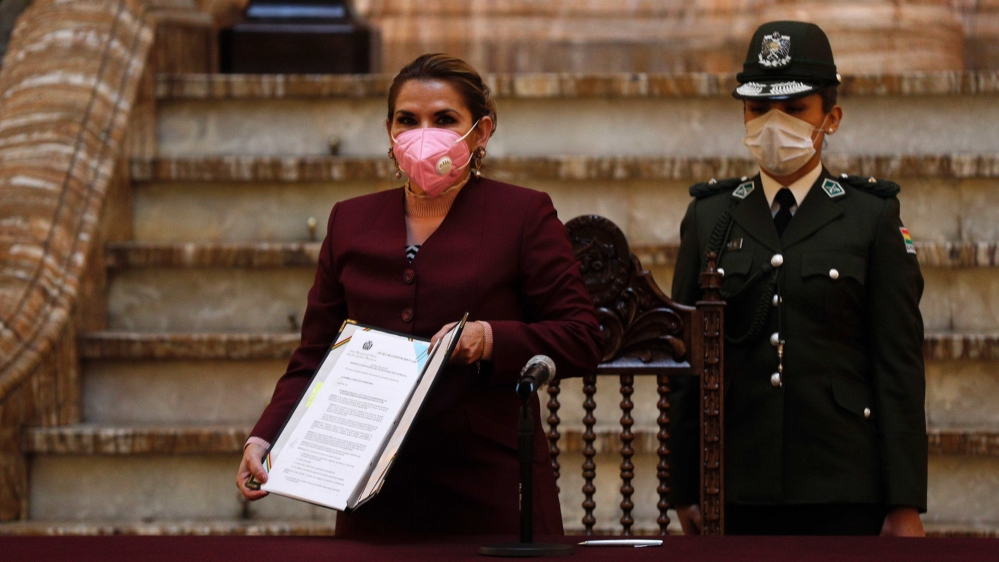

But despite the relative calm, tensions are still brewing in Bolivia among the main contenders of the elections: Morales’s powerful Movement for Socialism (MAS) party and a fragmented conservative opposition, which includes interim President Jeanine Anez, a right-wing leader who took over in a power vacuum last year, promising swift new elections.

Anez, who has sustained heavy criticism for her handling of the coronavirus pandemic, has also been accused of seeking to delay the vote to salvage her own election prospects and to consolidate her grip on power.

In a tweet last week, Anez called for a national dialogue to reach a consensus around the October 18 election date.

“Bolivia has two paths,” she said in a tweet. “The path of blockade, mourning and pain that the MAS proposes, or the path of dialogue, health, economic reactivation, and generation of jobs that we are proposing.”

Bolivia has reported more than 100,000 coronavirus cases and 4,058 deaths. The disease has sickened top government officials – including Anez herself – and overwhelmed hospitals and funeral homes.

Officials have been accused of corruption in ventilator procurements, and rights groups have blasted her government for arresting political opponents under the guise of the spread of “misinformation.”

“We are concerned about the human rights situation in Bolivia,” Jose Miguel Vivanco, director of Human Rights Watch’s Americas division, told Al Jazeera in a written statement.

“Since it took office in November of last year, the interim government has sought charges of terrorism, sedition and other crimes against Evo Morales supporters based on generic allegations, without actual, tangible evidence that the accused had committed any crime,” Vivanco said.

Government restraint

In response to the latest street blockades, Anez’s government had threatened to deploy police and military forces onto the streets to ensure the passage of medical supplies, after saying more than 30 coronavirus patients had died because oxygen could not be delivered to hospitals. Protest organisers denied that they had prevented medical necessities, ambulances or fuel from passing through the blockades.

But the move sparked fears of a return to last year’s violence, when two dozen of Morales’s supporters were killed during clashes with security forces.

“These street blockades were the first big test of how MAS politics or street politics would perform in post-Morales Bolivia,” said Carwil Bjork-James a scholar of Bolivian protest movements at Vanderbilt University,

“There was a big question of whether the government would show restraint or not, and they did not resort to deadly force, even though some parts of the right-wing base wanted them to,” Bjork-James told Al Jazeera.

Morales served as president of Bolivia from 2006 to 2019, spearheading efforts to reduce poverty, shift the country to a mixed economy and supporting Indigenous rights.

Although Morales had said in 2014 he would not try to serve a fourth term, he skirted a constitutional ban through the courts and ran in an October 20, 2019 election marred by allegations of fraud.

After widespread protests across the country, Morales resigned in November and fled first to Mexico, then Argentina.

His many supporters continued to back him, giving him, Bolivia’s first Indigenous president, power even in exile.

“We must not fall for provocations that want to lead us to violence,” Morales said in a tweet this month. “Only with the people in power democratically and peacefully will we be able to resolve crises and that means elections now, with a final and immovable date,” he said.

No debemos caer en las provocaciones que nos quieren llevar a la violencia. Solo con el pueblo en el poder democrática y pacíficamente podremos resolver las crisis y eso significa elecciones ya, con fecha definitiva e inamovible.

— Evo Morales Ayma (@evoespueblo) August 11, 2020

But the blockades, mainly organised by labour unions and Indigenous groups, proved unpopular among many Bolivians after they caused food and fuel shortages and increases in food prices. And some protesters broke away from the main protest demand for an election and instead demanded Anez’s resignation.

The blockades also continued for days even after Morales urged them to stop.

“These protests have shifted, divided and fractured the MAS a little bit,” said Jorge Derpic, assistant professor in sociology, Latin American and Caribbean studies at the University of Georgia. “There seems to be a fracture, as well, between the MAS and some social organisations,” Derpic said.

But despite the seeming fissure, Derpic says MAS remains the largest, most popular and powerful political force in Bolivia, and it is expected to perform well in the first round of the election. The MAS prospects are less clear in the second round of voting, scheduled for November.

“They are a party that’s already established, and unlike the other parties, they have a stable constituency,” Derpic says.

A July poll showed a narrow lead for the MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce, with 24 percent, followed by 20 percent support for Carlos Mesa, a centrist former president. Anez came in third with 16 percent.

Penaranda believes that while the pandemic has dealt a heavy blow to Anez’s popularity and legitimacy, which escalated to demands from her own party that she not run, the MAS has lost support as well.

“The government has been confronting many challenges, the pandemic, corruption allegations, roadblocks – and they have not been able to resolve any of these problems,” Penaranda said. “But the MAS has also lost some support due to these roadblocks,” he said, “and come election day, they might be punished for it.”