Cambodia’s democratic dream in shreds 30 years after Paris accord

The historic agreement was forged in the spirit of post-Cold War optimism, but was tested almost immediately.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia – As a teenager, Prum Chantha was optimistic about Cambodia’s democratic future.

It was 1991 and the Paris Peace Agreement, bringing years of conflict following the brutal rule of the Maoist-inspired Khmer Rouge to an end, had just been signed. Cambodians were looking forward to choosing their own leaders and picking up the pieces of their broken country.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCambodia union leader faces court verdict as crackdown continues

No justice: A year on, Thai dissident still missing in Cambodia

Jailed, in hiding, expelled: Cambodia’s Mother Nature crackdown

“After the 1993 election, I [thought] our country is prosperous; our country is no longer a communist country,” she said.

Now, 30 years after the historic accord was signed, Chantha, a trader and a housewife, finds herself fighting for the release of her husband – a supporter of what was once the main opposition party – and her 16-year-old son.

Her husband was arrested in 2020 and her son earlier this year. She says their fate is proof the 1991 agreement has not been respected.

“I did not think then that the country could turn out this way,” Chantha said.

“They arrested my husband on the charge of incitement and treason as he had prepared to welcome Sam Rainsy on the 9th November,” the 43-year-old said, referring to Cambodia’s most prominent exiled opposition leader. ”He has been in jail for more than a year and a half now.”

Her husband Kak Komphear, 55, is one of more than 100 supporters of the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) who have been arrested and jailed after Cambodia’s Supreme Court dissolved the party in November 2017 as its popularity surged.

Menaced by violence

Signed in October 1991, the Paris Peace Agreement brought together the four factions fighting for control of Cambodia after Vietnam invaded in 1979 to remove the Khmer Rouge.

With support from Vietnam and the then Soviet Union, Hun Sen’s People’s Republic of Kampuchea, which would later form the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), controlled Phnom Penh, but it had become bogged down in a struggle with removed Khmer Rouge fighters, backed by China; and forces led by the country’s former King Sihanouk, as well as a republican group led by Son Sann, which had Western backers.

The agreements laid the foundations for a democratic political system and elections.

The United Nations took over the administration of the country, deploying 16,000 peacekeepers and organising the vote, in which 90 percent of the population took part.

The royalist FUNCINPEC party won the election but amid threats from some in the CPP, a power-sharing agreement was crafted with FUNCINPEC leader Norodom Ranariddh as the so-called first prime minister and Hun Sen as the second prime minister.

In July 1997, after months of tension and a grenade attack on an opposition rally that killed more than a dozen people, Hun Sen moved against the royalists, and seized power for himself.

Since then, he has only tightened his grip, and the process has accelerated in recent years.

“There are many major concerns but the most important one is the way democracy has been destroyed in the name of stability,” said Sorpong Peou, a professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Ryerson University. “Dissolving the CNRP is against the Peace Accord’s democracy pillar, which is more or less an international peace treaty.”

Hun Sen’s move against FUNCINPEC led to at least 41 cases of execution of political opponents, according to a 1997 report compiled by the UN human rights office.

Ten years after the power grab, which is usually referred to as a “coup”, Human Rights Watch (HRW) Director Brad Adams said Hun Sen’s ability to navigate the domestic and international political fallout had “set the country on the course to Hun Sen’s almost total dominion over political and military power in Cambodia”.

Adams was an official at the UN human rights office in Phnom Penh in 1997.

“No one now believes [as a few did at the time], that if an opposition party obtained more votes than the CPP that Hun Sen would relinquish power,” he wrote.

Like many strongman leaders, Hun Sen has sought to equate “stability” with his rule.

“The PPA [was] intended not only to provide an immediate solution to end conflict but also to bring long-term peace by uniting political actors around a common commitment to the democratic and human rights provisions entailed in it,” said Astrid Noren-Nilsson a senior lecturer at the Centre for East and Southeast Asian Studies at Sweden’s Lund University. “Since then the government highlights its own peace achievements, superseding the PPA and its concerns for liberal democracy and human rights, citing that this has already been integrated into the Constitution.

“Peace is very much a part of everyday political discourse in Cambodia at this moment, but it has been redefined by the government as emanating from the dismantling of the opposition party CNRP which it has labelled treasonous.”

Opposition removed

CNRP, a combination of two small parties led by Kem Sokha and Sam Rainsy, was dissolved after the 2017 commune election in which it won about 40 percent of the seats, raising expectations that it might even win sufficient support to dislodge the CPP in the following year’s general election.

Kem Sokha was charged with treason, and more than 100 of the party’s senior leaders were banned from politics for five years. Dozens of other opposition leaders, including Sam Rainsy, fled the country for fear of arrest.

Since then the authorities have turned their attention to the party’s members and supporters, with hundreds arrested and jailed. Sokha, who is now under house arrest, could face up to 30 years in prison if found guilty of treason.

The CPP, meanwhile, has every seat in parliament.

“PPA has given birth to democracy in Cambodia. But Cambodian politicians and citizens are responsible for building democratic society with support from international communities,” said Yang Saing Koma, head of the Grassroots Democratic Party (GDP), a small party that was established in 2015 and has maintained a low profile.

“However, our old politicians have been fighting to strengthen their own power rather than building democratic institutions.”

The international community has urged the Cambodian government to return to the PPA and its framework for a multiparty democratic system.

“The international community needs to stay engaged and put pressure on the ruling party without threatening to undermine it. The international community has to persuade the government to be inclusive of other parties,” Sorpong Peou added.

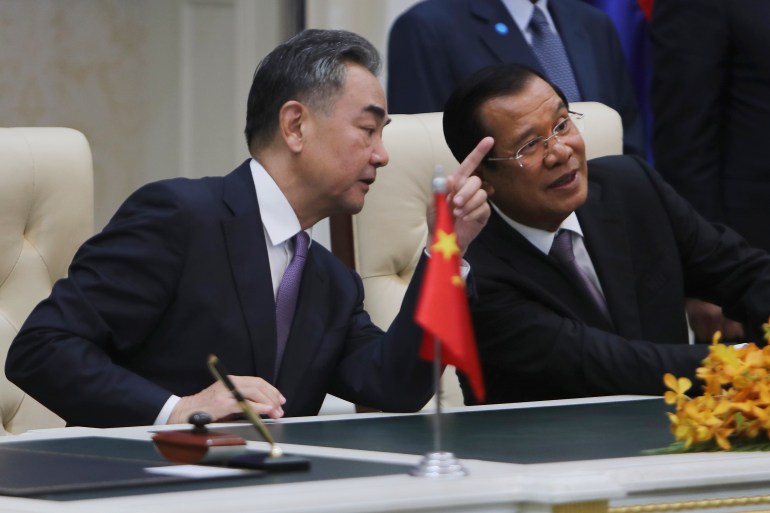

But the influence of the world’s liberal democracies on Phnom Penh has faded in recent decades, and Cambodia has shifted closer to China which is Cambodia’s largest source of aid and investment.

Of the $3.6bn of foreign direct investment last year, about half came from China, according to the World Bank’s most recent economic update. China is also Cambodia’s largest official creditor.

“I am concerned that the ‘system of liberal democracy on the basis of pluralism’ as envisioned under the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements to take root in Cambodia has not yet materialised,” UN Special Rapporteur on Cambodia Vitit Muntarbhorn told Al Jazeera. “Cambodians are still waiting for substantive and genuine power-sharing to happen in the country.”

“Importantly, commune elections will take place in 2022 and national elections are due in 2023, and they require full transparency and related guarantees.”

It was, after all, the CNRP’s strong election performance that triggered the government’s crackdown.

“Their worst nightmare is the loss of power, so they decided to undermine democracy by fabricating the so-called ‘colour revolution’ narrative as an excuse to arrest CNRP leaders and ultimately dissolve the CNRP, using the CPP’s political control over the courts,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for HRW.

Robertson says the dissolution was a violation of the PPA and Cambodia’s constitution.

‘Scorched earth mentality’

Phay Siphan, the government spokesman, denies that Cambodia has broken the accord, insisting the CNRP was dissolved because the party – by allegedly planning what the government claims were a “colour revolution” – was in conflict with the law.

He insists the government “can’t allow” the party to operate.

“Our constitution is the foundational law that we have to exercise,” he said. “We have integrated the spirit of the Paris Peace Agreement into our constitution.”

Monovithya Kem, the daughter of opposition leader Kem Sokha says the international community needs to do more.

“The PPA and our constitution guarantee multi-party democracy where people can choose their party and leaders,” she said.

“Since 2017 this fundamental right to choose has been taken away from about half of the country. Without the CNRP, the party of choice for half of the country’s constituency, there is no genuine multi-party democracy.”

Amid the continuing crackdown, Chantha’s son, who is 16 years old and has autism, has been charged with incitement and insulting public officials online.

In September, the UN expressed concern at his arrest.

“This case is particularly disturbing because the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – to which Cambodia is also a party – requires authorities to consider the best interests of children with disabilities and provide appropriate assistance,” the experts said in a statement.

“We are extremely concerned that the child was interrogated without a lawyer or his guardian, which violates the Cambodian Law of Juvenile Justice and international human rights standards.”

HRW’s Robertson says the arrest of Chantha’s son underlines the “scorched earth mentality” of the Cambodian authorities towards any criticism.

“This is a blatant disregard for the rights of a person with a mental disability,” he said. “The persecution of the father, as part of the many arrests and trials of CNRP supporters across the country, shows the government has decided it just doesn’t care about the provisions of the Paris Peace Accords requiring the upholding of human rights and support for multiparty democracy.”

Chantha has pleaded with the government to release her husband, her son and the many others who have been arrested for expressing their ideas or concerns.

And she is calling on the international community, which came together 30 years ago to chart a democratic way forward for Cambodia, once again to intervene.

“I was not an activist. I was a housewife,” she said. “But since they arrested my husband, I have protested with other women and mothers whose husbands or fathers are in jail in order for them to be released. They are not guilty.”