Just how strong is the Chinese military?

China is investing in advanced weaponry and equipment, and overhauling its military command structure to modernise its armed forces.

Shanghai, China – Amid repeated air incursions close to Taiwan, and reports that China has tested hypersonic weapons, the world is paying closer attention to the modernisation of China’s armed forces and its pursuit of ever more sophisticated weaponry.

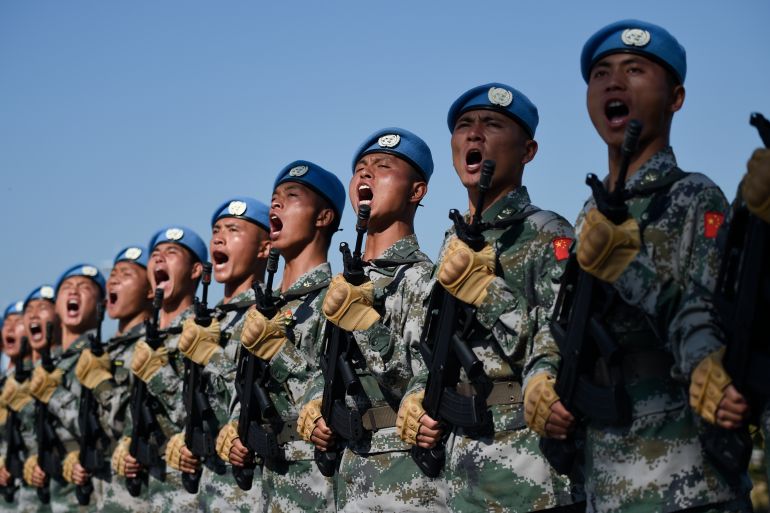

Once hailed by the Communist Party as having defeated past adversaries with only “millet plus rifles”, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has now grown into the world’s largest fighting force, with more than two million active personnel.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTop US general: China missile test ‘very close’ to Sputnik moment

China says Taiwan ‘has no right’ to join UN, after US nod

US intel warns China could dominate AI, gain military edge

Under President Xi Jinping, China has become more diplomatically assertive and shown an increased willingness to back up its claims over disputed territory with demonstrations of its military prowess. Neighbouring countries, and the United States have been watching closely.

“The increasingly loud voices sounding alarm of a potential China-US conflict in the South China Sea mostly came from the fact that the US is now seeing China on equal footing because of the latter’s growing army,” said Yin Dongyu, a Beijing-based analyst on the Chinese military. “And that’s quite a good indication of China’s growing military strength already.”

In recent months, the navies of the US and its diplomatic allies have sailed regularly through Asia Pacific waters – including the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait – to assert navigational rights in international waters.

In October, the US announced AUKUS — a new security alliance with the UK and Australia — that will lead to Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines from the United States.

Washington has also stepped up weapons sales to Taiwan, which is modernising its military and developing so-called asymmetric warfare capabilities to thwart any attack from Beijing, which claims the island as its own.

President Tsai Ing-wen this week confirmed media reports that the US had been providing Taiwan with specialist military training for more than a year.

“No one can say without hesitation whether China and the US would go into real conflict over Taiwan or South China Sea, but with China’s growing army, no one wants to see that happen,” Yin said.

Rapid naval expansion

The PLA’s ground force has traditionally been China’s foundation for asserting power in the region. It took the lead recently with India at the two countries’ Himalayan border, for instance.

Within its ranks, there are more than 915,000 active-duty troops in its ranks, dwarfing the US, which has about 486,000 active soldiers, according to the latest Pentagon China Military Power Report.

The army has also been stocking its arsenal with increasingly high-tech weapons.

In 2019, the DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missile, which experts say could hit any corner of the globe, was unveiled during the National Day military parade. But it was a DF-17 hypersonic missile that caught most people’s attention.

This year, it was reported China had actually tested hypersonic weapons twice – once in July and once in August – with a top US general describing the breakthrough as almost a “Sputnik moment“, referring to the 1957 satellite launch by the Soviet Union that signalled its lead in the space race.

With the South China Sea emerging as a flashpoint, the PLA is also developing its navy.

China claims the sea almost in its entirety amid competing claims by Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now the largest navy in the world, according to the government’s defence white paper, and its submarines have the capability to launch nuclear-armed missiles. To support the navy, China also has so-called maritime militia, funded by the government and known as “little blue men”, which are active in the South China Sea, while this year Beijing authorised its coastguard to fire on foreign vessels.

“China’s military strength has been significantly boosted by a large number of new weapons being added to the arsenal, especially in its Navy force,” said Yin. “That’s where the country’s army is showing some of its fastest growth.”

The air force has also grown into the largest in the Asia-Pacific region and the third largest in the world, with more than 2,500 aircraft and roughly 2,000 combat aircraft, according to an annual report by the US’s Office of Secretary of Defense published last year.

Most notably, the air force now possesses a fleet of stealth fighter jets, including the J-20, China’s most advanced warplane. It was independently developed and designed to compete with the US-made F-22.

Globally, China is also stepping up weapons’ exports to other developing countries with the goal of developing warmer relationships with friendly nations amid the regional competition.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, China’s weapons exports went mostly to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Algeria over the past decade.

Over the same time period, China has also been one of the world’s leading exporters of armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, with customers including the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, according to SIPRI.

“You see loads of UAVs being exported to the Gulf because the US Congress banned many countries from purchasing them from the US over human rights concerns, and China is soon filling that gap,” said Yin.

But China’s arsenal of headline-grabbing weapons, and seemingly unstoppable military growth masks an opaque command system, endemic corruption, and questions over the quality of its recruits.

The corruption stems largely from a tradition of nepotism and favouritism, and a general lack of oversight, while recruitment is suffering because despite some incentives, the younger, well-educated Chinese that the military wants are more attracted to the booming private sector.

That has left the PLA reliant on conscription for about a third of its manpower. Every province has an annual conscription quota, with each conscript required to complete two years of military service. This year, after a delay because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the military began holding recruitment and induction twice a year instead of once. It has also begun allowing more “second enlistments.”

And despite accumulating more advanced weapons in recent years, the PLA still has a large amount of older and more outdated equipment, some of it built using technology from the former Soviet Union, which collapsed 30 years ago, according to analysts.

China’s navy, for example, has more ships than the US – with 360 vessels – but the fleet consists mostly of smaller vessels. It has only two large aircraft carriers, the Liaoning and Shandong, with the third aircraft carrier Type 003 still under construction. The US has 11 aircraft carriers, the most of any country.

Additionally, the lack of training to operate and maintain the newly developed weapons has also hindered the army’s ability to reach “jointness”, according to a 2018 report published by the RAND Corporation, a US-based think-tank, referring to an army’s ability to command its various forces simultaneously to achieve its military goals.

“Corruption and an outdated command structure have left a very negative impact on the army,” said Shi Yang, a Beijing-based Chinese military analyst. “The large number of relatively outdated weapons also restricted Chinese army’s combat ability.”

Learning from the US

Potentially more of an issue, however, according to some analysts, is that the PLA simply lacks contemporary combat experience.

“It was 1979 when China last engaged in real world conflict – and that was in Vietnam,” Shi explained. “Without fighting real wars, some might argue that the [PLA] might not be able to live up to its expectations.”

VIDEO: #PLA Eastern Theater Command Naval Aviation Force recently tasked new pilots in live-fire missile target practices in a round-the-clock drill with multiple types of warplanes. pic.twitter.com/TF147lqmgZ

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) October 7, 2021

The military units still organise various exercises resembling real combat. Earlier this month, for example, China intensified its military drills near Taiwan, with mass air force incursions into the island’s air defence zone. In the same time period, the army also conducted ground drills in southeastern Fujian province – directly across the sea from Taiwan – amid increasingly loud assertions over its claim that Taiwan is part of its territory.

Some say a lack of real-world combat experience is not necessarily detrimental. Such lack of experience “wouldn’t erode China’s military strength in any significant way”, according to Shi.

“The military power of the Chinese army in modern conflict will mostly depend on technology, which has been steadfastly marching towards the right direction,” Shi said.

President Xi has taken a number of steps aimed at addressing some of the military’s shortcomings.

Borrowing from the US military, he has established a new army structure that gives the Central Military Commission, chaired by the president, more direct leadership over the armed forces.

Under the sweeping reforms, five “theatre commands”, geographically located across the country, were established in 2016. The Army, Navy, and Air Force divisions in each area report directly to the theatre command, ensuring the PLA operation is more effectively integrated.

Tackling corruption has been a cornerstone of Xi’s presidency. In the armed forces, that has led to the purge of hundreds of officials accused of taking bribes and other forms of corruption.

Xi is also channelling more money to the armed forces with an ever larger defence budget. In the 2021 fiscal year, 1.36 trillion yuan (roughly $209.16 billion) was allocated to defence — 6.8 percent more than last year.

It remains a fraction of the US defence budget, however, which amounted to $705.39 billion in 2021.

“Many countries in the region have seen China as a threat, and the US is also in that group, so with the growing Chinese military strength, other countries, with the help from the US both explicitly and secretively, are trying to catch up,” Yin Dongyu said of the escalating arms race in the region. “With China’s more assertive attitude towards its territorial claims, I don’t see this arms race to end anytime soon.”