Countering ‘love jihad’ by celebrating India’s interfaith couples

Last week marked the 100th day of a campaign called India Love Project, started by former journalists, that celebrates interfaith love or marriages.

New Delhi, India – Last week, India’s Supreme Court refused to hear petitions challenging the constitutional validity of religious conversion laws passed by right-wing governments in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand states, saying the high courts in these states should decide on the matter.

The petitioners said innocent people, mainly Muslims, were being unfairly penalised under the so-called “love jihad” laws, and that at least two other Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-governed states, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, were also planning similar laws.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia police stop interfaith marriage citing ‘love jihad’ law

Indian state criminalises religious conversions by marriage

What is behind India’s ‘love jihad’ legislation?

“Love jihad” refers to a conspiracy theory propagated for more than 10 years by India’s right-wing groups that accuse Muslim men of luring Hindu women for marriage to forcefully convert them to Islam.

A day after the Supreme Court order on “love jihad” laws came, a campaign called the India Love Project (ILP) marked the 100th day of its formation on February 4.

Started by a group of three former journalists in October last year, ILP aims to celebrate stories of interfaith love or marriages – considered taboo in a country divided along caste, religious and ethnic lines – on social media.

The campaign, with steadily growing followers on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, says it advocates “love and marriage outside the shackles of faith, caste, ethnicity and gender”.

Cofounded by a journalist couple, Priya Ramani and Samar Halarnkar and their friend Niloufer Venkatraman, the project invites people to submit stories about themselves or their families that help others understand that love transcends religious and communal identities.

“This is not fiction. These stories and couples have already happened, they exist. People have made choices and some have braved odds to be with the person they love,” Venkatraman told Al Jazeera.

Venkatraman’s was the first story to feature in ILP, where she talked about her Parsi mother and Tamil Hindu father.

Ramani says the idea of creating ILP came when right-wing politicians started taking aim at interfaith marriages as the “love jihad” controversy grew bigger towards the end of last year.

“We began discussing it actively last year,” she says, adding that the trigger was the bullying popular jewellery brand Tanishq faced when it was forced to withdraw its TV advertisement featuring an interfaith couple, where the boy was a Muslim.

In that same month, October 2020, that Yogi Adityanath, a saffron-clad Hindu monk who is the BJP’s chief minister in Uttar Pradesh state, said those who practice “love jihad” will not be spared.

His government promulgated an ordinance making religious conversion a non-bailable offence, with penalties up to 10 years in prison if found guilty of using marriage to force someone to change their religion.

All this despite the central government telling parliament last year that no cases of “love jihad” were reported by any of the investigating agencies.

“In my view, the concept of ‘love jihad’ is an attack on Hindu girls. They can’t make a choice because we have this politics,” says Tanvir Aeijaz, a professor of political science at Delhi University.

“I am surprised why liberal feminists don’t pick up on this issue.”

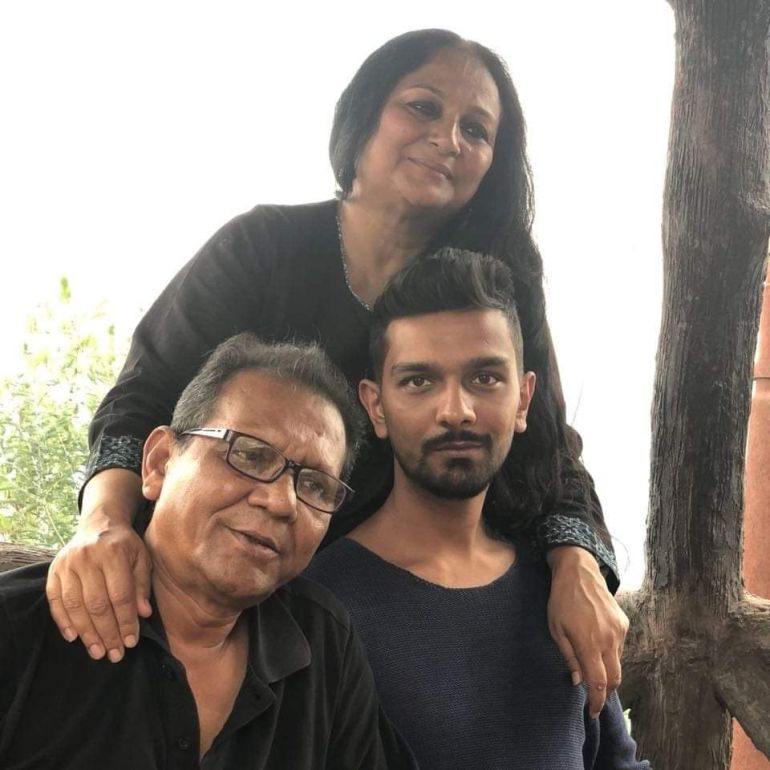

Aeijaz is married to Vinita Sharma, a Hindu who also teaches at the same university. Their story was featured on the ILP, where the couple shared how they met in 1997 and got married after dating for six years.

“Our families were concerned about our kids. We got married in 2003 in the backdrop of the Gujarat riots. We were scared. I asked my friends to join us in the court,” he says.

In 2002, more than 1,000 people – an overwhelming majority of them Muslims – were killed in religious violence in the western state of Gujarat, the home state of Prime Minister Narendra Modi who was then the chief minister.

The couple named their daughter Kuhu, now 13. “We liked the name and it didn’t have any religion in it,” says Aeijaz.

He lauds the ILP for its campaign amid the growing backlash against Muslims. “These are small but very strong interventions that are trying to build a counter-narrative.”

Shainaz Shaikh is a Muslim, who married Sanket Devle, a Hindu from the western state of Maharashtra, in 2012.

“He loves chicken biryani and I love misal pav [a delicacy in the state of Maharashtra] and we tease each other how we were born in the wrong families,” Shaikh wrote on the ILP page.

India’s Special Marriage Act, 1954 allows marriage between individuals of different faiths.

But Tanweer Kamal, a lawyer in Patna High Court in the eastern state of Bihar, says he faces a lot of problems when trying to register such marriages.

Kamal says he has so far filed papers for at least 70 interfaith and intercaste marriages. He says many interfaith couples settle for a marriage ceremony held according to the traditions of one of the partners, while others opt for religious conversion where a partner adopts the other’s religion.

Nivedita Jha, author and president of Bihar chapter of South Asian Women in Media, says she did neither and married under the Special Marriage Act.

Jha is married to Shakeel, a doctor based in Patna, who goes by his first name only. She says they married in 1987 against the wishes of their families.

“It wasn’t easy in those days. My mother fainted when she heard about it. My father didn’t have an ideological problem but he said the extended family might have an issue,” she says.

During the religious riots that erupted in the aftermath of the 1992 demolition of a Mughal-era mosque in the neighbouring Uttar Pradesh state, Jha was pregnant. When their son was born the next year, they named him Pushkin Shanib.

“We both loved the Russian writer Pushkin and for his last name, we combined our names. We didn’t want any identity politics in his name,” she says.

Jha says “love jihad” laws are “against the soul of the constitution”.

“All the people in this country have religious freedom. Jihad is done when we go to war. In love, there is no war,” she says.

Ramani says she receives a lot of messages from people who say they find reassurance in such love stories.

“My partner and I are facing a lot of hostility due to our interfaith backgrounds and I cannot stress enough how relevant and healing your page is. Each story brings both smile and tears. Keep doing the good work,” one such message reads.

Ramani says the project now wants to curate more intercaste and LGBTQ love stories.

“Who doesn’t like a good love story?” asks Niloufer.