Why are COVID cases rising in Europe despite vaccination efforts?

Infectious strains, sluggish vaccine rollouts and a lax attitude to physical distancing have seen cases surge in some countries.

Across the European Union, COVID-19 cases have begun to rise steadily, from 200 per million in mid-February to 270 per million last weekend.

That level is still a long way off from the EU record of 490 per million in November, but a worrying trend nonetheless.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGrit and grace: US women business owners persevere through COVID

Russia identifies two cases of South African COVID variant

EU regulator ‘convinced’ AstraZeneca benefit outweighs risk

“We are weary of it all, but we’re determined, too,” a doctor at an Italian hospital told Al Jazeera, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Most regions in Italy, including Rome and Milan, are now classified as high-risk and there will be a three-day national lockdown over Easter.

“We were in a period of relative stability around December and January, but now the figures are worsening again very quickly,” said the doctor.

In her large hospital in central Italy, there are concerns about the average age and medical condition of recent COVID-19 patients – many have observed a shift. It is no longer mostly elderly people with underlying illnesses in the wards, but also previously fully healthy 50-year-olds.

“It’s a drastic situation,” she said.

Across much of Eastern Europe, too, in countries such as Hungary, Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic, COVID-19 infection figures are soaring.

More infectious strains, sluggish vaccine rollouts

Last year, Italy became the Western epicentre of the pandemic when the virus first surged across Europe, and the images of military trucks in Bergamo carrying bodies are still fresh in memory. Soon after, many European countries became overwhelmed.

But academics have cautioned against viewing the recent surge as a Europe-wide third wave.

“You have to take it nation by nation for now,” Guillermo Martínez de Tejada, professor of Microbiology and Parasitology at the Universidad de Navarra in northern Spain, told Al Jazeera.

Like Italy, Spain was particularly hard hit by the first wave in 2020.

“Some countries are clearly in trouble, but in others, like Portugal and Spain, figures aren’t nearly so high,” said Martínez de Tejada.

“There’s been a big increase in terms of testing everywhere, too. The more you look for COVID-19, the more you’re going to find.

“Then there’s the question of these new strains, particularly the British one”, reportedly 70 percent more infectious. “That’s undoubtedly boosted cases, too.”

Martínez de Tejada is equally convinced that Europe’s sluggish vaccination rates are also behind the surge.

As of last week, according to Bloomberg’s Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker, the EU had administered eight first doses per 100 people, compared with 33 for the United Kingdom and 25 for the United States.

The slow rollout has been attributed to seemingly chronic delays in supplies dating back to January, when reduced shipments of the Pfizer vaccine sparked rows with Italy.

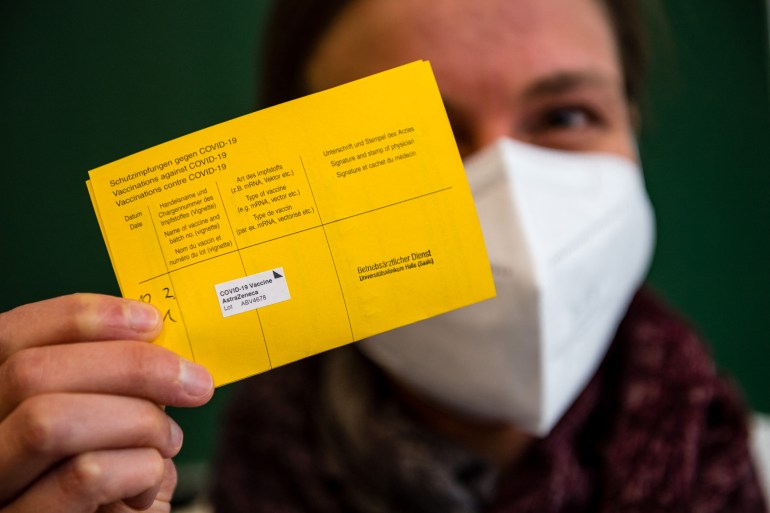

Since then, there have been issues in France and Italy with the Moderna vaccine, a reduction by two-thirds of AstraZeneca’s promised total of 90 million doses by the end of March, and last week, there were reports that supplies of the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine, recently approved by the European Medicines Agency, may also be delayed.

Factor in the recent round of suspensions of the AstraZeneca vaccine in multiple countries in the wake of reports that a tiny number of people developed blood clots after receiving the jab, and it is easy to see why Europe’s vaccination drive has been so hamstrung, and how that could affect the rise in cases.

“If we had vaccinated more ambitiously, sooner, I think we would have been able to put a brake on these situations,” said Martínez de Tejada.

“Cyprus has the highest level of vaccinated people in Europe right now, and even there it’s nowhere near enough to create herd immunity, which is 60 percent of people at the barest minimum.

“Although each country will progress differently I don’t think we’re going to get to that point before the end of the summer. Certainly not in Spain.”

Conflict between economic concerns, lockdown measures

Beyond the short-term factors, other academics claim the way some European governments have dealt with the health crisis meant cases would inevitably rise again.

“Broadly speaking, worldwide there have been three different ways of reacting to the virus,” Joan Benach, professor of Public and Occupational Health at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, told Al Jazeera.

He said at one end of the spectrum, there was a “laissez-faire” strategy such as in the US and Brazil. At the other, in some East Asian nations, a strict “COVID-zero” policy “that tried to stamp it out altogether with strict collective measures”.

The third path, according to Benach, dominates in Europe – “much more reactive than proactive, and heavily influenced by business sector demands”.

“Rather than try to wipe out the virus altogether, here it’s been more about learning with it – toughening up restrictions when contagion numbers were high, lowering them again as they got better.

“It’s a permanent game that won’t end until there’s mass vaccination, and that will take months, probably the entire year, to happen.”

The underlying conflict between economic interest and social restrictions emerged again recently when German company Eurowings announced an extra 300 flights to Mallorca over Easter after Germany eased travel warnings for some parts of Spain.

Hotels in Germany are currently closed, the German Foreign Office advises against non-essential tourist travel, and Spanish people are banned from all non-essential travel outside their region.

But the tourists from Germany to Mallorca will need only a negative PCR test to enter the country, and no quarantine will be required on their return.

At the same time, in Germany on March 14, the 14-day average COVID-19 positive case numbers rose 26 percent, to more than 17,000.

Last week, Lothar Wieler, the president of the Robert Koch Institute which handles pandemic data in the country, warned of “the beginning of a third wave”.

Benach said: “Another Euro-wide wave isn’t happening yet … [But] given the number of waves we’ve had so far, another one wouldn’t be a surprise. The key question is how to prevent it.”

Given the vaccine delays, the tension between business needs and lockdown measures, and the newer, more infectious COVID-19 virus strains, that looks like an uphill struggle.

Back in Italy, the anonymous hospital doctor argued that a lack of respect for physical distancing measures could reverse any positive steps made as vaccines are rolled out.

“While maybe 80 percent of people obey the restrictions, there’s another part, above all younger adults, who still feel they’re invulnerable and who happily flout the rules about social distancing and so on,” she said.

“It’s infuriating and it threatens to render the sacrifices made by those fighting the pandemic almost useless. But we’re not giving up.”