Sarah Everard murder highlights threats faced by minority women

Recent government figures show Black Britons and people of mixed ethnicities are more likely to experience sexual assault.

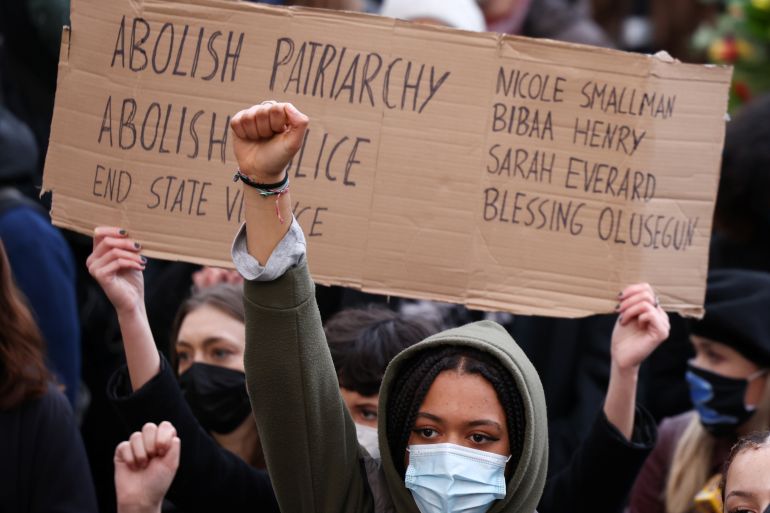

London, United Kingdom – The murder of Sarah Everard has placed the UK’s public institutions under intense scrutiny, raised questions as to why prosecutions against sexual abusers remain at an all-time low, and highlighted the threats faced by women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds, according to experts.

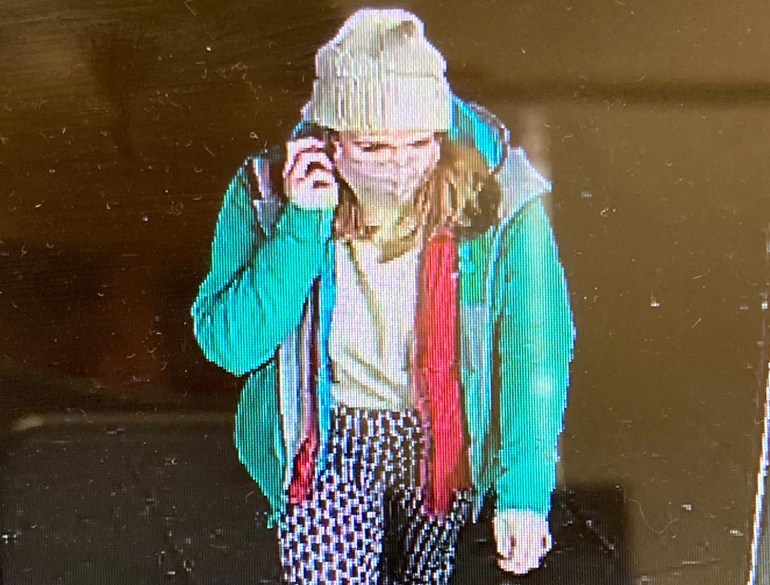

Everard went missing on March 3 – she was last seen walking home from a friend’s house near Clapham Common, in London. Her remains were found in woodlands a week later in Kent, a nearby county, and identified on March 12.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe murder of Sarah Everard and the shadow pandemic

Sarah Everard killing: UK police officer faces trial in October

Sarah Everard’s murder: No justice for us without radical change

The failure to arrest the suspect, London police officer Wayne Couzens, on February 28, when he was reported for indecent exposure at a fast food take away, has also prompted concerns – would Everard still be alive had appropriate action been taken sooner?

The case darkened the national mood and at a London vigil for the 33-year-old on Saturday, anger grew when officers forced women protesters to the ground and arrested them.

The event had been officially cancelled because of coronavirus restrictions but some observers claimed the police should have turned a blind eye and allowed the protest to go ahead.

Later that day, police officers were alleged to have ignored a woman when she tried to report a case of indecent exposure as she walked home from the event.

‘Police officers look at race and culture before safeguarding’

Welsh government adviser Yasmin Khan told Al Jazeera that a poor police response to complaints about sexual predators – a “recurring theme” – is deterring victims of sexual violence to come forward.

New figures published on Thursday by the government’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed that in England and Wales, fewer than one in six women and one in five men report crimes of sexual assault to the police.

The ONS figures also showed adults of Black and mixed ethnicity were more likely to experience sexual assault.

Khan, who founded the Halo Project – a support network for abused ethnic minority women and girls – said police discrimination is leaving minority victims of sexual abuse particularly out in the cold.

She said the Halo Project has handed to the Home Office evidence of police prejudice against minority victims – a report which has been escalated to the investigation stage by the Independent Police Complaints Commission.

“It means we’re one step closer to establishing that change can be brought about in the future,” she said.

The report focused on abuse in minority communities and alleged that police forces across England and Wales were failing victims and “denting their confidence in police”.

“It takes so much courage to make disclosures about abuse so it’s important we get the right response on the first meeting; telling the same story to five different agencies is not acceptable, but this is what happens.”

Blessing Olusegun was 21 when her body was discovered on a beach in East Sussex last September.

Her death was deemed "unexplained" by police.

Too many deaths have gone uninvestigated.

Blessing's family deserve justice #JusticeForBlessinghttps://t.co/39FmDOYnHE

— Bell Ribeiro-Addy MP (@BellRibeiroAddy) March 15, 2021

Cases of sexual abuse among ethnic minorities rarely achieve justice because police forces across England and Wales, where representation is lagging, lack cultural understanding and have “a fear of offending communities”.

“We found police officers look at race and culture before safeguarding and protecting. They consult with independent advisory groups that include community members known to victims, and place emphasis on community impact instead of police investigations.

“Sex is already a taboo amongst certain Black, Asian and ethnic minority (BAME) communities, so the shame and dishonour leading to reprisals and revenge is not considered. The pressure on victims is immense.”

What happened to Sarah Everard could happen to any of us. Black women, in particular, are doubly victimized when authorities don't take their assaults seriously, and the media & public are less likely to give women of color the same coverage and support they give to white women.

— Full Frontal (@FullFrontalSamB) March 18, 2021

Khan said police need to be trained in “trauma-informed police investigations” and communication with rape victims from ethnic minority backgrounds.

“Asking suspects to come in for voluntary interviews does not mean you are investigating sexual assault. This removes the power of restrictive bail conditions and gives offenders time to collude with others and destroy evidence,” she said.

Everard’s murder must lead to “a watershed moment that improves the justice system”, she said, adding that while she welcomed amendments earlier this month to the law on domestic violence, they were “disappointing” for failing to include migrant women.

One of the many things I love about the Black women on my timeline is that they always show up for all women. Our feminism is truly intersectional. It’s a shame the same courtesy isn’t always extended to us. #SarahEverard #BlessingOlusegun

— Masivanda (@Ms_Reeny) March 12, 2021

Societal change needed

Evidence of sexual abuse is one of the biggest challenges in rape cases.

According to the ONS, of almost 59,000 rape cases recorded in the year to March 2020, there were just 2,102 prosecutions. In 2019, this figure was higher – at 3,043 prosecutions.

Scottish lawyer and criminal justice expert Safeena Rashid told Al Jazeera that “unconscious bias” may be at play when cases of abuse within relationships go to court.

“There may be societal perceptions of what a relationship is meant to look like, or moral judgements involved that are not meant to form part of cases, but might inevitably creep in.”

Further, when victims know their abusers, they may be less inclined to share evidence.

“For example, where something has happened on a date, there might be an element of shame which prevents a complainer wanting to report the matter or proceed with evidence,” she explained.

“In other relationships, there might be an emotional attachment. Relationships bring with them complex emotions and it is sometimes difficult to come to terms with harm occurring in an environment where there is the occasional love displayed.”

In Scotland, the justice system is distinct from the one ruling England and Wales.

“What I have seen in Scotland is a willingness to address the issue of violence against women and make going through the justice system as bearable as it possibly can be for complainers, with measures in place to protect vulnerable witnesses,” said Rashid.

But regardless of the advances being made, the demand for change should not be confined to institutions.

“There is no getting away from the fact we live in a society where violence against women, particularly unwelcome sexual advances, are not taken as seriously as it should be at societal level,” said Rashid.

“It is time for us to stop explaining away a pinch on the bum as ‘boys will be boys’ and start empowering women to be able to stand up to any form of abuse.”