Families of victims seek justice over French air strike in Mali

France denies UN report that 19 unarmed civilians were killed in a January air strike on a remote Malian village.

Families of people killed in a French air strike on a wedding in a remote Malian village have called for the prosecution of the military personnel involved in an operation the United Nations has concluded could amount to a war crime.

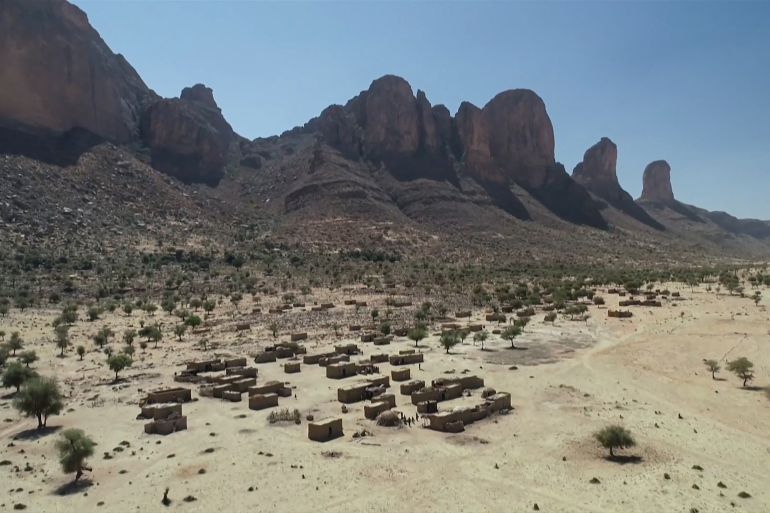

Nineteen attendees of a wedding party in the village of Bounti were killed when French warplanes struck on January 3, according to a bombshell UN report on Tuesday, its first ever investigation into French military operations. Three suspected militia fighters were also killed.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsMali needs climate solutions, not more troops

Attackers on trucks and motorbikes raid Mali base, kill 33 troops

The findings contradict French claims, reiterated this week, that 30 militia fighters had been killed in the attack which took place in Mali’s restive central region.

French denials, analysts say, are likely to spur escalating anti-French sentiment among Malians, less than a year after the government was overthrown in a military coup and as the cycle of violence continues to result in a mounting civilian death toll.

France’s 5,000-strong Barkhane force was deployed to northern Mali in 2014 to dislodge fighting that has now spread to central Mali and into neighbouring countries Burkina Faso and Niger, deepening French involvement across the Sahel.

Unpopular in both France and Mali, Barkhane has been dubbed France’s forever war, an unwinnable and costly military quagmire, comparable to the United States’ experience in Afghanistan.

The report by the UN peacekeeping force in Mali (MINUSMA), based on more than 400 interviews and the analysis of more than 150 documents, constitutes a rare criticism of French forces.

“The majority of those hit in the strike were civilians who are protected from such attacks by international humanitarian law,” said the UN in its report, which recommended that the French and Malian authorities “conduct investigations into possible violations of international humanitarian law and human rights” and compensate the victims.

The strike “raises significant concerns … including the obligation to do everything that is practically possible to verify that the targets are indeed military objectives,” it added.

Hamadoun Dicko, youth leader of Mali’s largest ethnic Fulani organisation, and the first to sound the alarm over civilian casualties, said: “We are very happy because [the report] confirms 100 percent what we said.”

Within days of the strike, Dicko’s organisation, Tabital Pulaaku, had identified at least nine civilian casualties and posted their names on Facebook.

Dicko said that victims’ families he had spoken to welcomed the UN report but were demanding justice.

“They are happy and expecting to get justice because those responsible must now be arrested and the families compensated,” he said.

But France dismissed the findings on Tuesday, describing it as based on “unverifiable local testimony” and “unproven hypotheses”.

Speaking from Mali’s capital Bamako on Thursday, French Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly doubled down further, rejecting the accusations and stressing the “determination” of France “to continue the fight against terrorism”.

Mohamed Salaha, an independent journalist based in Bamako, told Al Jazeera that a refusal to acknowledge the loss of Malian life was heightening anti-French resentment, adding that the report’s findings had been welcomed by most Malians.

Salaha said that many view France as complicit in reprisals by allied Malian forces, turning a blind eye to abuses the UN said in 2020 amounted to war crimes.

He also pointed to a French air strike last week in the eastern village of Talataye, which local officials said killed six civilian males aged 15 to 20 – a toll also disputed by Paris.

“All those incidents against civilians make people angry against France. They have drones and sophisticated equipment to identify civilians. Malians want France to pay attention to civilians,” Salaha said.

“We want Malian leaders to take action to punish those people who have bombed the 19 civilians,” he added.

In recent years, sporadic demonstrations against France’s military presence have mushroomed into large-scale anti-French rallies decrying perceived neocolonialism as much as the needless loss of life.

Police dispersed angry protesters with tear gas two weeks after the strike on Bounti in January, while anti-French fury returned to the capital’s streets last Friday.

Nadia Adam, research officer at the Institute for Security Studies, said that while rural populations had first welcomed the French as liberators from the chaos of roving armed groups, mounting allegations of civilian atrocities could now see protests spread among the tiny mud-brick settlements hundreds of kilometres from the capital.

“Whether these allegations are actual or perceived, the lack of accountability for security sector misconduct undermines civilian relationships with defence and security forces,” she told Al Jazeera.

“Transparency and accountability are very important aspects in measuring the successes of the fight against insecurity in Mali.”

But many feel that Mali’s internal political instability and close French ties hamper the chances of accountability.

Mali’s leaders supported France’s version of events in January and are expected to release a statement about the report only after concluding talks with France and European Union military partners currently under way in Bamako.

Meanwhile, a transitional government installed in January after a coup last August is viewed with mistrust and has yet to find its feet.

“One thing that is clear is that the victims will remain victims,” said Salaha.

“We doubt that our government will be able to urge France to recognise what has happened.”

Dicko also harbours doubts. “Seeing those responsible face justice is one of our greatest wishes but I am not sure if that will happen,” he said.

“No army is perfect, so it’s high time they admit that they have killed civilians, “ he added.

“I think that they should stop telling lies and tell the truth.”