As COVID wave rages in Nepal, hospitals run out of beds, oxygen

Record numbers of infections and deaths sweep Nepal, prompting fears its second wave may be worse than India’s.

Kathmandu, Nepal – The Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital in the Nepali capital, Kathmandu, is packed – so packed that in some cases two patients share one bed – as a second COVID-19 wave overwhelms the country’s health infrastructure.

Health experts and front-line medical workers have described the situation as “near-apocalyptic” as they face shortages of hospital beds and oxygen, the national vaccination campaign grinds almost to a halt and the numbers of dead are so high that mass cremations are being held.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsNepal ex-royals test COVID positive after India’s Hindu festival

Nepal battles worst forest fires in years as air quality drops

“We have been treating patients in every corner of the hospital premises. We are even using the garage to admit as many patients as possible,” said Beli Poudel, a nurse at Sukraraj.

“We do not turn any patient away, we try to accommodate them despite our limited capacity,” Poudel told Al Jazeera, adding that more than 120 COVID-19 patients are being treated in the 104-bed hospital, which has only 24 ICU beds. The hospital, experiencing a huge influx of severely affected patients in the pandemic’s second wave, had already doubled its capacity.

For several weeks now, many of the staff at Sukraraj – the only facility in Nepal specialising in tropical and infectious diseases – have lived in hostels or on hospital premises away from their families.

With just over 21,000 tests on May 19, Nepal logged 8,173 COVID cases and 246 deaths, the highest number recorded since the pandemic broke out last year. Health experts believe the real numbers could be much higher as testing remains low. More than 5,600 people have died since the pandemic began, nearly 2,000 in the past few weeks alone, according to official figures.

The pandemic has particularly affected the Kathmandu Valley and the country’s western lowland bordering the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The region is one of Nepal’s least developed, with a large concentration of Indigenous people and ethnic and religious minorities.

Shahbaz Ahmed, a resident of Nepalgunj in western Nepal, lost his three brothers – Zahir, Ejaz and Imtiyaz – to coronavirus in the first week of May.

All three brothers in their 40s were receiving treatment at Bheri government hospital following health complications.

“The doctors couldn’t save them despite trying their best. Maybe it was Allah’s wish,” Shahbaz told Al Jazeera over the phone.

Zahir, the youngest among seven siblings, was a former member of the under-19 national cricket team. “He (Zahir) was the fittest among all brothers,” Shahbaz said.

Shahbaz, who is mourning in isolation like the rest of his family, rued the crippled health infrastructure.

“I am grateful to health workers because they are risking their lives to save others. But I think the government and politicians aren’t fulfilling their duties,” he said.

Biren Budhathoki, a resident of Dang in western Nepal, said a delayed diagnosis led to the death of his 38-year-old cousin on May 14.

Most hospitals, except for the large ones in cities, do not have a machine for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, crucial for timely diagnosis and avoiding preventable death.

“By the time we got the result for the PCR test, my cousin had already developed pneumonia. He passed away shortly after we shifted him to COVID-19 hospital from a local nursing home in Salyan,” said Budhathoki.

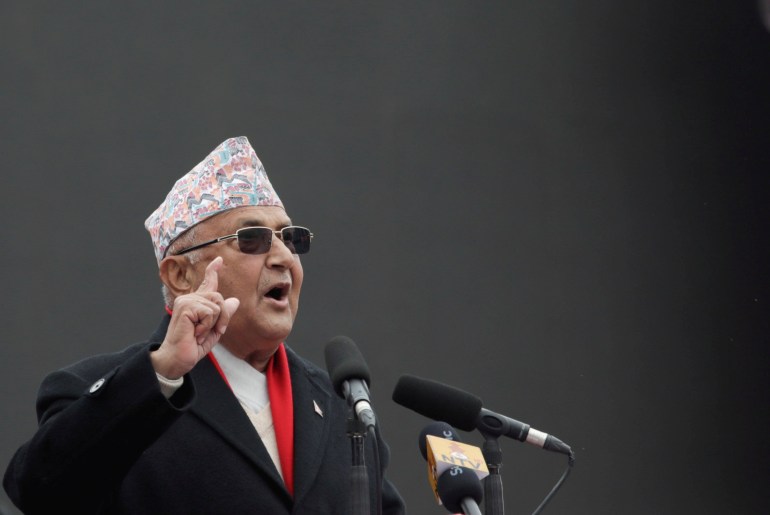

The rising number of cases in the country has set alarm bells ringing, with Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli and the health minister publicly admitting that hospitals were overwhelmed by patients.

“The number of infections is straining the healthcare system; it has become tough to provide patients with the hospital beds that they need,” Oli wrote in an opinion piece in the Guardian newspaper, urging the international community to assist.

Experts have linked the spike in Nepal to the devastating second wave in its northern neighbour, India. Up to mid-April, deaths from COVID had been confined to single digits. At 6.51, Nepal’s daily rate of deaths per million is now the worst in South Asia.

The shortage of beds is a common problem across Nepal, which has approximately 18,900 general, 1,450 ICU and 630 ventilator beds across the country. New Delhi, India’s capital with a smaller population, has more than 4,000 ICU beds.

Anup Bastola, chief consultant at Sukraraj hospital, told Al Jazeera all the patients in the ICU were in critical condition.

“While we have 24 ICU beds, we only have 12 ventilators. All of them need ventilators but we have not been able to provide them,” he said.

Nepal’s number of doctors per capita is also one of the lowest in the world, with 0.17 doctors per 1,000 people, while India has 1.34 doctors per 1,000 population.

At least 12 ICU patients have lost their lives due to oxygen shortages since last week, according to media reports.

Pramod Paudel, a doctor at Bharatpur Hospital in central Nepal, said his hospital was admitting fewer patients than its actual capacity, accepting only 144 patients despite a capacity of 200, due to disruptions in the oxygen supply.

“Sometimes when the oxygen stocks are about to run out, we worry whether we will be able to get more for our needy patients. We cannot take more patients because of the oxygen shortages,” Paudel told Al Jazeera.

In recent weeks, medical aid, including oxygen tanks, has been trickling in from across the globe, but officials say that it is nowhere near enough to meet demand. Many Nepalese living abroad have pitched in. Nearly one-third of Nepalese work abroad.

On Wednesday, the Ministry of Health and Population confirmed it had detected a third COVID variant in the country, B.1.617.2, a variant first detected in India which is considered highly contagious. The new variant was detected in 97 percent of the samples collected from 35 districts in the country. The other two variants are B.1.617.1 and B.1.1.7.

“We might be somewhere around the peak as the infection rate, by the government’s own conservative estimates, is between 40 to 50 percent,” said Basu Dev Pandey, one of Nepal’s foremost virologists and former head of the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division under Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population.

Over 80% of those infected will recover, according to epidemiologists, but the recovery rate is not an indicator to gauge the impact of the pandemic.

It's deaths per million that indicates how good or bad the situation is.

Nepal fares the worst in South Asia. pic.twitter.com/NuhGUbYyAn

— Arpan Shrestha (@arpanshr) May 20, 2021

“The severity of infection is very similar to India. Moreover, we also share a long open border where the cross-border movement remains largely unregulated. The flights between the two countries are still in operation,” said Pandey. Kathmandu has banned other international flights.

Health experts in Nepal had warned in March about the danger of a more lethal variant of the coronavirus entering via India.

The warning was not unwarranted, with Nepal sharing a porous border of nearly 1,700km (1,100 miles) with India. Millions of Nepalese work in Indian cities such as Delhi and Mumbai and many started to return in April as several Indian states imposed lockdowns in the wake of the country’s devastating second COVID wave.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Oli has come under fire for prioritising politics over the country’s pandemic response – dissolving the parliament and dividing political opponents who were trying to remove him from office. At the same time, the prime minister continues to recommend unproven herbal medicines, going as far to say that Nepalese have better immunity to withstand the virus.

At a function in Kathmandu last month, the prime minister claimed, albeit with a caveat, that gargling with hot water in which guava leaves had been boiled could keep COVID at bay. “Even vaccines cannot guarantee 100 percent protection,” Oli said.

Gehendra Lal Malla, a professor of political science at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, said Oli’s unfounded remedies and light remarks on the immune system had misled people to take the virus lightly.

“It was understandable that Nepal doesn’t have good medical infrastructure like the West, or China and India, but there was ample time and money to buy ICU beds and ventilators. But Oli was more preoccupied in securing his position than saving lives,” Malla told Al Jazeera.

Although experts have called on the government to speed up vaccinations, the much-hyped immunisation drive has fallen short of expectations after the Serum Institute of India (SII) suspended the supply of AstraZeneca jabs, despite receiving payment in advance. SII – the world’s largest vaccine maker – stopped exports to prioritise India, which has seen tens of thousands of deaths in the past couple of months.

Nepal, a poor country of 30 million, has vaccinated barely two million people, mainly front-line workers, since it started inoculations on January 27. So far, the country has procured more than three million vaccines, including 800,000 doses from China and 348,000 doses from the WHO-led COVAX facility.

Defending the government’s handling of the COVID situation, former minister Mani Chandra Thapa told Al Jazeera all political parties should be blamed for focusing more on power games instead of the pandemic.

“It’s true that the government could have worked more effectively. But let’s not forget that other parties were creating hurdles by trying to oust the government in the middle of the pandemic. Therefore, all of us should take the blame and move forward to fight the virus,” Thapa said.