El Salvador constitutional crisis ushers in ‘period of darkness’

Dismissal of top judges and attorney general could do irreparable harm to democracy, rights groups and lawyers warn.

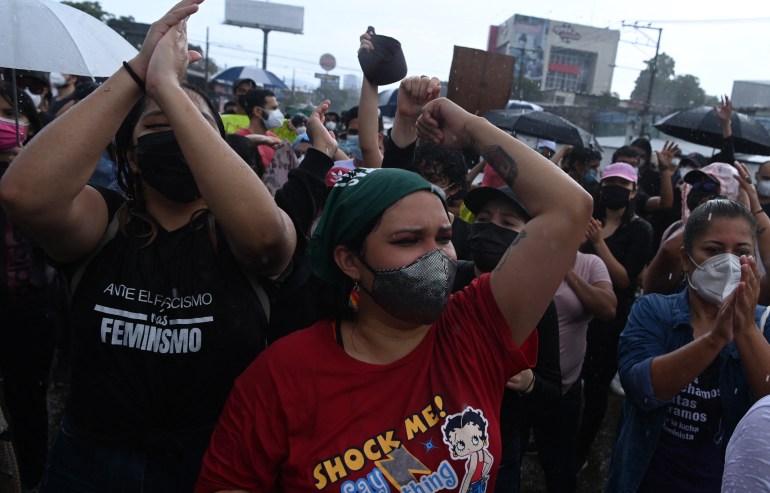

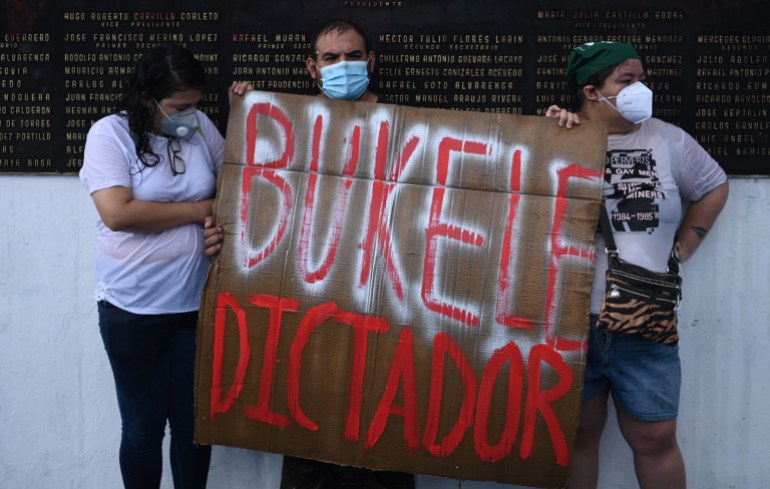

Salvadoran lawyers and human rights groups fear newly sworn-in lawmakers have dealt an irreparable blow to the country’s young and fragile democracy after the legislators removed officials from key offices over the weekend.

The removal of the country’s attorney general and Constitutional Court judges eliminates two of the remaining checks on the power of the administration of President Nayib Bukele, who has been consolidating control of democratic institutions since he took office in June 2019.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHow Nayib Bukele won over voters in an unlikely place

Allies of El Salvador’s Bukele win absolute majority in Congress

Salvadoran human rights defender Celia Medrano said it also signals the government wants to “keep themselves in power and crush any opposition”.

In a country that is still healing from a 12-year-long civil war that ended in 1992 and left 75,000 dead, Saturday’s parliamentary votes stir up old memories of an era of repression and human rights abuses and serve as a reminder of the fragility of the country’s democratic system.

“Everything indicates that this will be a long period of darkness in the country in terms of democracy,” Medrano told Al Jazeera.

‘Setting an example’

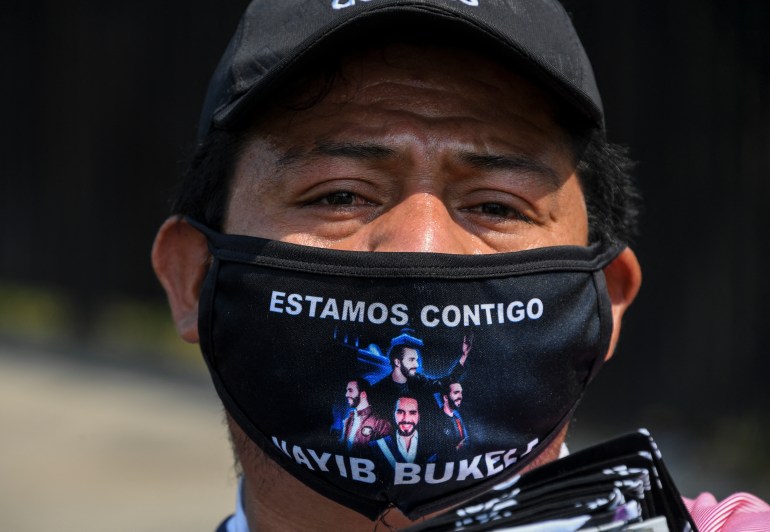

Bukele won the presidency in 2019 on an anti-corruption platform that appealed to voters fed up with the country’s two traditional parties, left-wing FMLN and right-wing ARENA. But without the support of the country’s legislators, many of his proposals were blocked in the first two years in office.

Institutions including the Constitutional Court, the attorney general’s office, and the ombudsman often acted as checks on his power.

In February, Bukele’s party Nuevas Ideas, or New Ideas, won 56 of 84 seats in the national assembly after an overwhelming show of voter support. When the lawmakers took office on May 1, they moved swiftly – and unconstitutionally, according to legal experts – to remove the five judges of the Constitutional Court as well as Attorney General Raul Melara.

Five new judges have already been appointed to the court by the new assembly. Three of the ousted judges have since formally resigned, citing personal reasons, but not before issuing a declaration of the unconstitutionality of their removal.

“With this, the legislative assembly is setting an example. They are saying to all other officials: ‘If you question the vision of the president, you can also be removed,'” said Manuel Escalante, a lawyer with the Institute of Human Rights at the University of Central America (IDHUCA).

Bukele and his supporters defended the actions as necessary to rid the country of corrupt officials of past administrations. “The people did not send us to negotiate. They’re leaving. All of them,” Bukele tweeted on May 3.

Also on Twitter, Suecy Callejas Estrada, one of the Nuevas Ideas legislators who led the initiative, defended the decision as constitutional, citing three articles to back up her argument.

Legal arguments

Yet legal experts have refuted this interpretation of the constitution, which does establish a process for removing officials from office, but only under limited conditions that legal experts say have not been met.

Officials can be removed from office for “specific causes previously established by the law” and a process of vetting new candidates to fill the newly vacated positions must be followed. The new legislators bypassed that in an ad hoc process, according to Escalante.

“The explanations that the assembly gave on Saturday were at no point legal explanations based in the legal system,” he said. “Instead what they expressed was simply a discontent with the constitutional court because they [the justices] were not in agreement with the constitutional interpretation of the president.”

Escalante added: “Their actions convey the message that the only one who interprets the constitution correctly is the president.”

Furthermore, the timing of the removal of the attorney general suggests a political motive, according to Medrano. “It’s important to point out that the removal of the attorney general was during a moment when he was investigating serious acts of corruption and links of the current government with organised crime,” she told Al Jazeera.

The president’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

International outcry

International human rights groups and United States officials immediately condemned the actions in El Salvador.

US Vice President Kamala Harris, who is leading the Biden administration’s efforts to work with Mexico and Central American countries to stem migration, said the administration has “deep concerns” about the events. “An independent judiciary is critical to a healthy democracy – and to a strong economy,” she tweeted on May 2.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken echoed these concerns in a call with Bukele on Sunday, the State Department said in a statement, while USAID, the country’s development agency, said an independent judiciary is “a necessary precondition for combating corruption and attracting investment” in El Salvador.

Bukele rebuffed these critiques, however.

“To our friends in the international community: we want to work with you, to do business, travel and to know us and help in what we can. Our doors are more open than ever. But with all due respect: we are cleaning our house … and that’s none of your business,” he tweeted on Saturday.

A nuestros amigos de la Comunidad Internacional:

Queremos trabajar con ustedes, comerciar, viajar, conocernos y ayudar en lo que podamos.

Nuestras puertas están más abiertas que nunca.

Pero con todo respeto:

Estamos limpiando nuestra casa.

…y eso no es de su incumbencia.

— Nayib Bukele 🇸🇻 (@nayibbukele) May 2, 2021

El Salvador’s constitutional crisis comes as the Biden administration has promised to prioritise strong democratic institutions in Central America.

“There’s a pretty clear message coming from the United States and I think that’s important,” said Geoff Thale, president of the Washington Office of Latin America (WOLA), a nonprofit that promotes human rights in the region. “But now they’re going to have to think about actions.”

Sanctioning corrupt government officials and appealing to Bukele’s interests – trade and the economy – are two potential ways the US could follow through with its commitment to building democracy, Thale told Al Jazeera.

Meanwhile, Salvadoran lawyers and human rights groups wanting to challenge the recent moves now face a dead end. Before, they could have turned to the Constitutional Court – but no more.

“By taking control of these institutions,” said Escalante, “they force us to face a situation in which whoever searches for justice or tries to control the abuse of power from the executive branch isn’t going to find it.”