Confederate Robert E Lee’s racist legacy fuels US renaming push

In the wake of racial justice protests, monuments and institutions honouring Lee are being reimagined or repurposed.

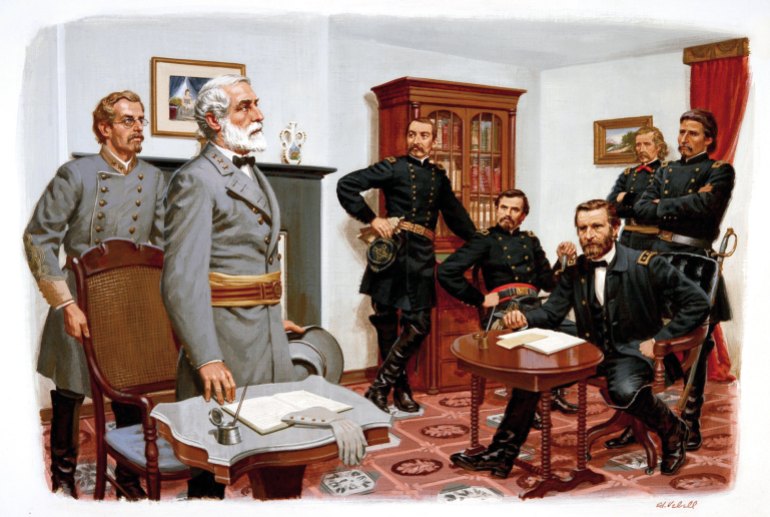

As the United States continues to grapple over race relations and symbols that venerate Confederates who fought to perpetuate slavery in the 1860s, communities across the country are considering new approaches to memorialising one of the rebellion’s most famous leaders: General Robert E Lee.

To this day, scores of buildings, roads, monuments and institutions bear Lee’s name. Thousands of children are educated at schools named after Lee; “Robert E Lee Day” is still celebrated every January in a handful of states, and the late general’s likeness appears on monuments and memorials in dozens of cities.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS: Maryland repeals Confederate call to arms as state song

Confederate general’s statue removed from US Capitol building

US: Confederate statue removed near site of 2017 far-right rally

Lee, a decorated military officer from Virginia who fought for the US before the Civil War and married into the family of George Washington, was responsible for some of the Confederacy’s most consequential victories in its fight to protect slavery.

To some, Lee was a man who nobly kept his allegiance to his home state of Virginia; to others, his decision to battle the federal government in an effort to break up the US made him a traitor.

But some are reconsidering continuing their attachment to Lee or shifting the way they approach a man whose legacy divides Americans to this day.

“What happens in our communities is a decision to be made not by people who are long dead, but by us today,” Adam Domby, a historian and author of The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory, told Al Jazeera. “There is a difference between learning about the Civil War and celebrating the Confederacy, and I think that is the crucial distinction we need to draw.”

In June, many institutions agreed to reconsider their approach to Lee or abandon his name altogether: Lee’s former home, which is located near Washington, DC, reopened to the public after a years-long renovation that shifted the focus to emphasise the lives of his Black slaves; a school in Florida named after Lee dropped his name; the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, voted to remove his statue from public land; the Virginia Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments for statue removal in Richmond; and a university named after Lee addressed a fierce debate over whether to keep its namesake.

“Lee has always occupied a unique place in the national imagination,” Eric Foner, a Pulitzer-prize winning historian of the Civil War wrote in The New York Times. “The ups and downs of his reputation reflect changes in key elements of Americans’ historical consciousness — how we understand race relations, the causes and consequences of the Civil War and the nature of the good society.”

Lee’s legacy received rehabilitation in the first half of the 20th century. He was celebrated in glowing biographies, remembered as an institutional namesake and memorialised as a southern hero in public displays of bronze and stone. In 1975, members of the US Congress, including now-President Joe Biden, voted to posthumously restore Lee’s American citizenship.

But in recent years, as Americans have begun to recalibrate their relationship with flawed men of history, the image of Lee has fallen.

“It is hard to establish a blanket rule, but the veneration of Lee seems more and more inappropriate now,” Foner told Al Jazeera.

In Jacksonville, Florida, a school board in a district with several schools named after Confederate icons, voted to rename them last week. One school with Lee’s namesake that opened as a segregated institution in 1928, changed its name to Riverside High School.

The decision came after five gruelling school board meetings that filled hours of debate. While many residents spoke in defence of preserving the name of the school, which also features a Confederate general as its sporting mascot, a poll (PDF) found that 59 percent of community residents with affiliations to the school supported changing it.

Virginia wrestles with Lee’s legacy

While the reckoning over Lee’s legacy spans many states, the debate has been particularly heated in Virginia, where he was born.

In Charlottesville, where white supremacists marched in 2017, the city council voted on Monday to remove a statue of Lee from a local park, and another statue of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson nearby. City council members first proposed removing the statues in 2016, a move that led to years of public debate, legal challenges and demonstrations both in support of and against the removal.

“We look forward to transforming our downtown parks by removing these racist symbols of Charlottesville’s past,” the council said in a statement.

In the city of Richmond, Virginia, which was formerly the capital of the Confederacy, a 13-tonne statue of Lee astride a horse has served as a lightning rod of controversy for years, but its role as a symbol of the debate was elevated in 2020 when protests erupted worldwide over the killing of George Floyd.

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam last year called for removing the statue, which is 18 metres (59 feet) high on a base now covered in graffiti. The state’s Supreme Court heard oral arguments this week.

Washington and Lee University, a college in Lexington, Virginia, where Lee once served as president, this week turned down calls to remove Lee’s name from the school, but agreed to take steps towards making changes to the institution. After months of debate and more than 15,000 comments submitted to the university’s board, the school finally released its decision.

“While we heard broad support for advancing our commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion on campus, we found no consensus about whether changing the name of our university is consistent with our shared values,” the university concluded.

The letter went on to apologise for its “past veneration of the Confederacy” and its use of slaves. The university diploma, which bears an image of Lee, will be updated without his likeness and a campus chapel named after him will be renamed “University Chapel”. The school also committed to halting the annual “founders day” celebration, held on Lee’s birthday.

After years of renovation, Lee’s former home in Arlington, Virginia, reopened to the public in June, but with considerable changes to its historical buildings and interpretive signs. The mansion, located in the Arlington National Cemetery and operated by the National Park Service, received a $12m rehabilitation that now elevates the stories of Black slaves who once lived on the property.

A bookstore that was previously located in slave quarters was moved to a non-historic building to use the space to tell about the history of slaves on the plantation.

“That was one of the primary goals of this project. To elevate the story of the enslaved people and the enslaved community at Arlington House,” National Park Ranger Aaron LaRocca told Al Jazeera. “We’re putting emphasis on those stories. We’re bringing them to the forefront.”