Decades after 9/11, what became of the US’s neoconservatives?

Few willingly describe themselves as ‘neoconservative’ as the label has fallen away from popular use.

In the weeks before former President Bill Clinton delivered his State of the Union address to Congress in 1998, a group of intellectuals, writers and policymakers penned an open letter to the president that made an impassioned case for “removing Saddam Hussein and his regime” from power in Iraq.

“We urge you to act decisively,” the letter, published through an organisation called the Project For The New American Century, read. “If we accept a course of weakness and drift, we put our interests and our future at risk.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBiden to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan by September 11

Pentagon survivors recall horror of 9/11 attack, reflect on war

Twenty years after 9/11, did US win its ‘war on terror’?

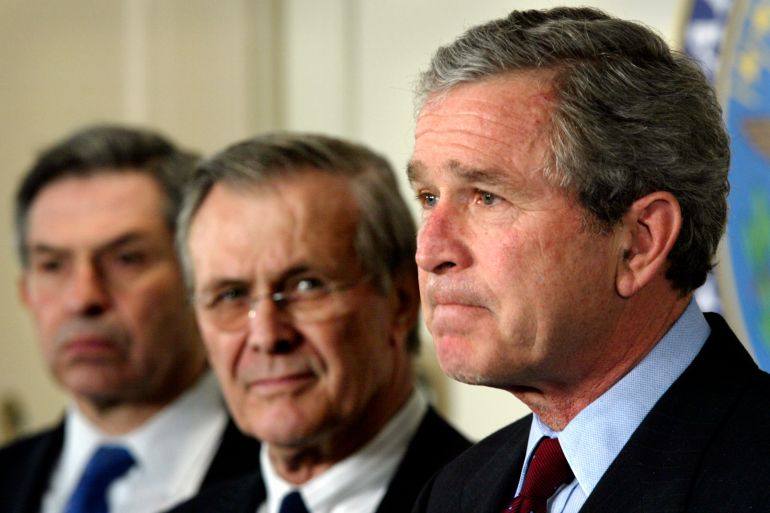

The letter stood as a statement of policy in concert with a school of thought commonly called neoconservatism. Although Clinton ignored their advice, the signers included names of men who would later hold sway as part of George W Bush’s presidential administration: Donald Rumsfeld, Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz, to name a few.

What followed over the next few years – US invasions of two nations that lasted decades – changed the course of history.

While the level of influence of the neoconservatives on the Bush administration is often debated, their heeded calls for a hawkish American presence defined the first years of the twenty-first century.

“Neoconservatives proved to be extremely influential in shaping American foreign policy after the Cold War,” said Stephen Wertheim, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and author of Tomorrow, the World: The Birth of US Global Supremacy. “Neoconservatives were one of the more cohesive intellectual and political groups that made a strident case for US global military dominance and, after 9/11, a series of open-ended wars.”

Today, as the last US troops have departed Afghanistan, weary after years of war, the legacy of the neoconservatives remains widely criticised.

“American conservatives assumed that military power would enable the United States to accomplish a radical ideological agenda, particularly in the Middle East,” said Andrew Bacevich, author of After the Apocalypse: America’s Role in a World Transformed. “That effort has proven to be a costly failure.”

In the early 2000s the term neoconservative – or when often used derisively, “neocon” – became part of the common American lexicon. But these conservative thinkers and practitioners who saw their foreign policy ambitions put into practice on the world stage were not new.

What was first used to describe a group of New York-based intellectuals and former liberals, neoconservativism has come to be defined by support for aggressive foreign policy through military might.

In the 1990s and 2000s, neoconservatives like Irving Kristol of The National Interest and Norman Podhoretz of Commentary were commonly lumped in with a younger generation of thinkers and fellow travellers, like William Kristol, foreign policy analysts Robert Kagan and Max Boot, Bush speechwriter David Frum and others who served in the George W Bush administration.

Through policy advocacy in Washington, think-tank papers and articles in conservative journals of opinion, this loosely aligned bunch included some of the loudest supporters of the war in Iraq and other forms of US foreign adventurism.

“They were the dog that caught the car,“ said Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age, a conservative quarterly critical of neoconservatives. “They got the chance to implement their most strongly desired objective. They got to make an attempt at creating an American empire. It was an empire for the sake of promoting liberal democracy as they understood it.”

Twenty years after the attacks on 9/11, an event that arguably set in motion the fulfilment of neoconservative foreign policy dreams, what has become of the neoconservatives?

In recent years, many of the former neoconservatives – or those aligned with them – have coalesced in opposition to former President Donald Trump. These so-called “Never Trumpers” refused to support Trump even after he locked up the GOP nomination in 2016 and some crossed party lines to support Biden’s presidency in 2020.

William Kristol, who had been affiliated with Republicans for decades, launched a new publication, The Bulwark, as a space for conservatives who opposed Trump. In 2020, Kristol supported Democrat Joe Biden for president, calling him “the simple answer” to defeating Trump. Still, Kristol has not abandoned his foreign policy instincts. In August, Kristol co-authored an open letter to Biden calling for him to bolster forces in Afghanistan, writing that “it is not too late to deploy forces to stabilize it, and ultimately turn it around”.

Frum, the Bush speechwriter who coined the phrase “axis of evil” and who in 2003 castigated conservatives who questioned the Iraq War effort as “unpatriotic” in the pages of the conservative National Review, has found a home at The Atlantic, a centre-left magazine. Frum has been a vocal critic of Trump, penning a book called Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American Republic.

Meanwhile, other Bush administration officials, like Doug Feith and Paul Wolfowitz, who worked in the Defense Department, have found safe havens in think-tanks.

The word “neoconservative” has largely fallen away from popular use and one is hard-pressed to find those who willingly use the term to describe themselves. Even as far back as 1996, Podhoretz wrote of neoconservatism using the past tense. More recently, in 2019, Boot called for abandoning it altogether.

“‘Neoconservatism’ once had a real meaning – back in the 1970s,” Boot wrote. “But the label has now become meaningless.”