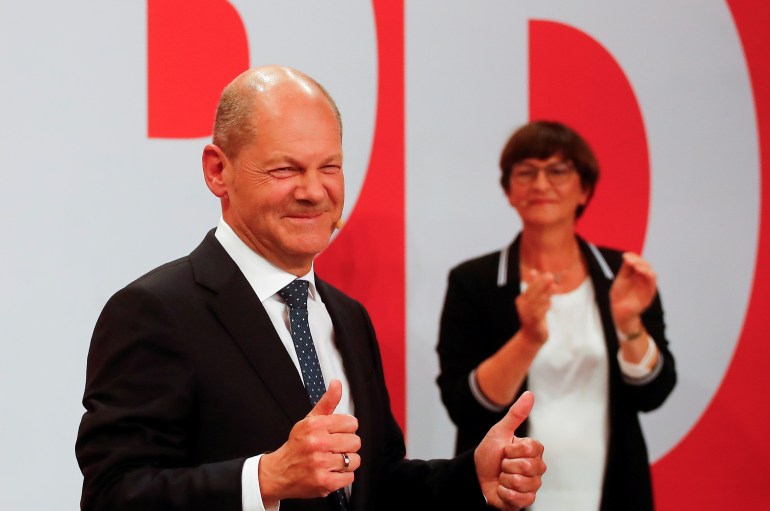

Who is Olaf Scholz, Germany’s successor to Merkel?

Scholz has become chancellor, ending Germany’s 16-year Merkel era.

Berlin, Germany – In late 2019, Olaf Scholz’s bid to lead the German Social Democrats (SPD) hit a brick wall.

Members voted instead for a lesser-known left-wing duo who promised to ditch the party’s loveless marriage with Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndia votes in first phase of marathon election as Modi seeks third term

G7 countries slam Chinese firms’ support for Russia’s defence industry

The Take: What would a third Modi term mean for India?

The days of the so-called “grand coalition”, under which Scholz served as finance minister and to which he remained loyal, were numbered. His own future was unclear.

But ultimately, it was the recognisable and widely respected Scholz that the party turned towards as its chancellor candidate.

For the first time since 2002, the SPD beat the Christian Democrats, by 26 to 24 percent, making Scholz the clear favourite to become chancellor once a governing coalition is formed.

Over the years, politicians and journalists have reached for many descriptors to capture Scholz’s signature impassive demeanour – comparing him at times to a smurf, a robot, and a mid-level bank clerk.

A proud son of Hamburg, the port city to which much of his political career has been tied, Scholz typifies its “Hanseatic” coolness.

“He’s very clear, he doesn’t take too many words,” said Mathias Adler, editor of the popular Hamburg newsletter Tagesjournal. “If you have a deal with him, he is reliable.”

Born in 1958, Scholz was raised in the east of Hamburg where, after finishing school, he studied law and became an employment lawyer.

A member of the SPD since his teens, he became a state senator at the age of 40 and was known for his tough positions on law and order.

He joined the Bundestag, Germany’s federal parliament, in 2002, becoming the party’s general secretary for the second term of SPD chancellor Gerhard Schroeder.

More radical in his youth, Scholz became a disciple of Schroeder’s Third Way politics, backing his plan to overhaul the German welfare system.

These reforms, known as “Agenda 2010” and intended to spur economic growth, were divisive.

By slashing benefits and worker protections, the traditional party of labour created a new class of poorly-paid and impoverished workers – an albatross that would remain around the SPD’s neck throughout the Merkel years.

After stints as chief whip and labour minister, he returned to Hamburg in 2011, where he became mayor.

There, Scholz set about rebuilding the SPD. He boosted housing construction, which had dropped to crisis levels, and improved the performance of schools.

He dredged the harbour to accommodate the world’s largest container ships and renegotiated contracts to finally complete the Elbphilharmonie, the concert hall that opened six years behind schedule and cost hundreds of millions of euros over budget.

“That’s one of his strengths, to negotiate and to make clear what he wants,” Adler told Al Jazeera.

As mayor, Scholz had a penchant for grandiose projects, pushing ahead with plans for a skyscraper, known locally as the “Scholz tower”, and proposing to host the Olympics – a bid soundly defeated by the city’s voters in a referendum.

“He feels very self-confident. Self-confidence that borders on arrogance,” Adler added.

Scholz hosted the G20 summit in 2017, against security advice. Scenes of chaos followed as the members of the city’s strong left-wing scene clashed with police, garnering worldwide media attention and embarrassing Scholz, who was forced to admit his error.

“The apology was not so easy for him,” said Adler.

In 2017, he was appointed finance minister by Merkel. Though long sharing the conservatives’ desire for minimal borrowing and balanced budgets, he appeared to change course after his humbling failure to become leader in 2019.

“It would be wrong to cut back investments in an economic crisis,” he told the newspaper Zeit in December that year, saying this had been done in the past but “will not happen with me”.

The next crisis was not long in arriving, and during the coronavirus pandemic, Scholz became a popular figure, temporarily lifting Germany’s constitutionally enshrined borrowing limits to dole out billions to keep businesses afloat.

In Brussels, he softened Germany’s traditionally hard line on sharing debt with other EU members and was instrumental in passing the union’s 750 billion euro ($869bn) coronavirus recovery package.

During an election campaign, his two rivals suffered embarrassing gaffes and accusations of career padding and plagiarism.

Unaffected by his own proximity to two major financial scandals, he earned another nickname: Teflon Scholz.

German prosecutors raided Scholz’s finance ministry just weeks before polling day, looking for evidence that one of its agencies was told to ignore suspicious transactions by Wirecard, a major financial firm that spectacularly collapsed last year after investigations uncovered billions in fraud.

Questions have also been asked about his role in the massive CumEx tax evasion scandal. Hamburg’s tax authorities failed to claim back 47 million euros ($54m) owed by a local bank, whose owner Scholz met several times. The bank has since paid the money back and Scholz has denied any impropriety.

“These cases are so difficult to understand,” said Ursula Munch, director of the Academy for Political Education in Tutzing. “It’s much easier for the public and for journalists, to talk about [embarrassing] videos, books and resumes than about financial surveyance.”

Scholz’s popularity continued to rise as the race drew to a close, far outpacing his rivals. In televised leaders’ debates, he hammered home the SPD’s plan to increase the minimum wage, boost social welfare and invest in climate protection.

Audience polls rated him the victor in each one, and the party hitched itself to his coattails.

Election billboards featured Scholz with his arms crossed and the simple message: “Whoever wants Scholz, vote SPD”.

In the final weeks of the campaign, conservatives turned to fruitless attempts to cast Scholz as a puppet controlled by more hardline left-wingers in the party.

Adler thinks the “astonishing” cooperation within the notoriously factional SPD is genuine, but that Scholz will not be manipulated.

“I think he will be his own man,” he said.