Economic woes, shifting ties complicate Pakistan’s flood recovery

Government seeking to generate much-needed funding but analysts say domestic and external challenges pose a risk.

Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistan has this week announced plans to host an international donors’ conference to help it recover from catastrophic floods that caused widespread devastation and major financial losses this summer.

The United Nations and France have also offered to hold a donors’ conference to generate funds for the country, which is among the most climate-vulnerable nations despite contributing less than one percent to global carbon emissions.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPhotos: Deadly floods wreak havoc in Kenya’s capital

China evacuates over 100,000 as heavy rain continues to lash south

Asia bears biggest climate-change brunt amid extreme weather: WMO

But many analysts believe that a globally faltering economy, a rising energy crisis and Western questions over Pakistan’s geopolitical alliances mean providing much-needed funding will remain a stark challenge.

“When the 2010 floods came, Pakistan was a darling because of the ongoing War on Terror and donor fatigue was also considerably less,” said Ali Tauqeer Sheikh, an Islamabad-based climate change analyst, referring to flooding more than 10 years ago that killed some 2,000 people.

“Now Western economies are struggling themselves, and currently our credibility has also taken hit over the years.”

At their peak, the recent floods left more than one-third of the country submerged, particularly affecting the southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan.

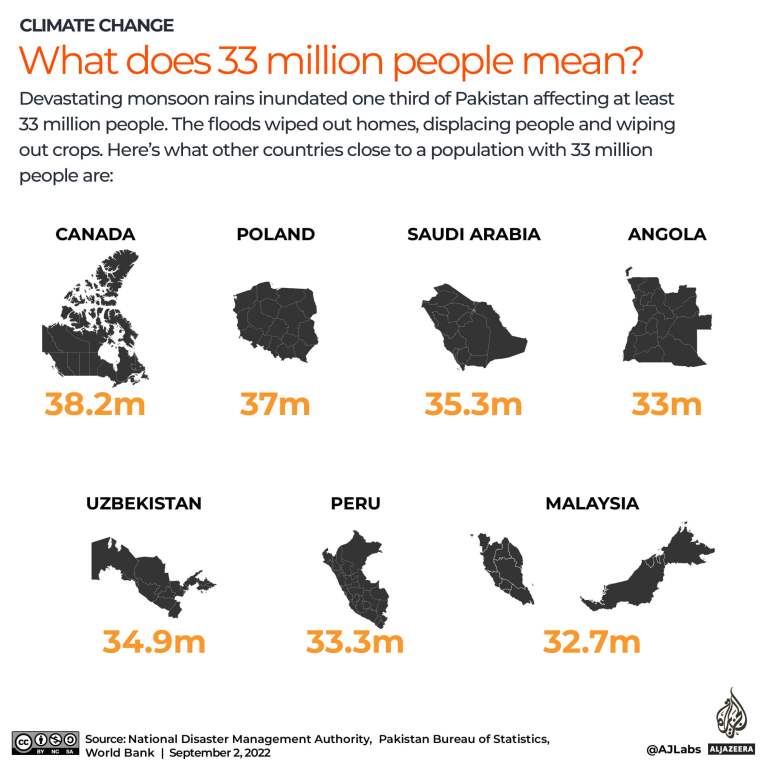

The latest government data put the death toll at 1,725 people, including 643 children, with more than 33 million people affected by what was described as “a monsoon on steroids” by the United Nations chief Antonio Guterres.

The deluge resulted in damage to more than 13,000km (8,000 miles) of road networks; some 3,000km (1,900 miles) of railway tracks; more than two million houses; hundreds of bridges; livestock and hundreds of thousands of acres of agricultural land.

After putting the initial damages figure at $10bn, the government subsequently revised it to upwards of $30bn. On Tuesday, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif said the World Bank had put the damages estimate at $40bn.

The UN this month revised an initial aid flash appeal for $160m to $816m. But Pakistani officials say the country so far has only received close to $100m of funds, despite higher pledges by friendly countries and global institutions.

“Pledges over $205m have been made, of which $90m have been committed or actualised,” a Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) spokesperson told Al Jazeera.

The spokesperson said that the sum of all the pledges made, including those responding to the UN appeal as well as separate multilateral and bilateral assistance, exceeds $1bn.

‘Economy in turmoil’

The floods have come at a time when Pakistan’s economy is already in a precarious situation, with a rising current account deficit, more than 20 percent inflation and the massive depreciation of its currency, the rupee.

The country only managed to avert a default in August when it secured $1.17bn in funds from the International Monetary Fund.

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s poverty rate is likely to rise between 2.5 and 4 percentage points due to the floods, according to the latest World Bank report released earlier in October. Nearly 20 percent of its 220 million people are already below the poverty line.

Speaking to the Financial Times this week, Sharif said the country is looking for additional funds for “mega undertakings” such as infrastructure reconstruction, and is seeking a moratorium or rescheduling of its debt obligations.

“There is a gap, a very serious gap, which is widening by the day between our demands and what we have received,” Sharif said.

Last month, during a visit to the United States to attend the United Nations General Assembly session, Sharif had told Bloomberg that Pakistan has spoken to European leaders to help Pakistan get a moratorium.

‘Lack of fiscal space’

Pakistan’s planning minister Ahsan Iqbal, who is also spearheading the flood reconstruction and rehabilitation, told the country’s national assembly on Monday that Pakistan was planning to host an international donors’ conference after the completion of an estimated damage assessment.

But Uzair Younus, director of the Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, said Pakistan’s macroeconomic indicators would pose a challenge for the government to raise additional funds.

Some analysts also believe that Pakistan’s inability to generate funds is a result of its gradual shift towards China, one of the United States’ main geopolitical rivals, for its economic and defence needs during the last decade. Pakistan’s external debt is more than $130bn, of which roughly $30bn is owed to China, which has also invested heavily in Pakistan as part of its Belt and Road Initiative.

Younus, however, said there are some domestic sources of money available.

“According to the UN, some $17.4bn a year are handed out to elites, redirecting a fraction of these benefits to flood relief and reconstruction can be quite impactful,” he said.

“It is time for Pakistan to realise that the hard work must first begin at home. The state needs to find a way to mobilise additional resources by taxing domestic sectors which are given tax exemptions and privileges.”

Retired Lieutenant General Nadeem Ahmed, the former chief of Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority, also questioned the government strategy of focusing more on infrastructure development.

“The government needs to focus on people first,” he said. “We must invest foreign aid into people-centric projects and use our own resources for infrastructure development. People need to be rehabilitated today whereas major development projects will take time.”

Younus concurred, stressing that the government needs to keep people front and centre in their rehabilitation and rebuilding plans.

“We need to hear from people on the ground. So long as a long-term human development plan is lacking, Pakistan will end up rebuilding things only for them to be washed away in the next catastrophe,” he said.