Will more Ukrainians flee to the European Union as winter bites?

The bloc says there are preparations for all scenarios, but analysts say support across the EU could wane as inflation soars.

Brussels, Belgium – As Russia’s war in Ukraine barrels into a tenth month, the colder winter months ahead are set to pressure a population with a strong resolve but limited resources.

This week, renewed attacks across the nation targeted critical infrastructure and wiped out power and water supplies in several cities, including the capital, Kyiv. The bombings were so severe that electricity in parts of Moldova was also struck out.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘Formula of terror’: Ukraine leader implores UN to punish Russia

Russian attacks plunge Ukraine, parts of Moldova into darkness

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Ukraine’s Western allies say, is using winter as a weapon. Observers claim he hopes the frigid weather will fuel a new refugee crisis and test Europe’s unity and support for Ukraine as inflation across the continent – with extortionate energy prices – soars.

“The Ukrainian people, because of Putin’s barbaric, terroristic attack on the country’s civil infrastructure, must face this upcoming winter with no electricity and, in many places, no running water,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said in a statement on Wednesday, a day of widespread assaults that plunged Ukraine into darkness.

She said the EU would continue standing by Ukraine “for as long as it takes”, words echoed by NATO on Friday.

“We are working hard to hit Russia where it hurts, to blunt even further its capacity to wage war on Ukraine,” she said.

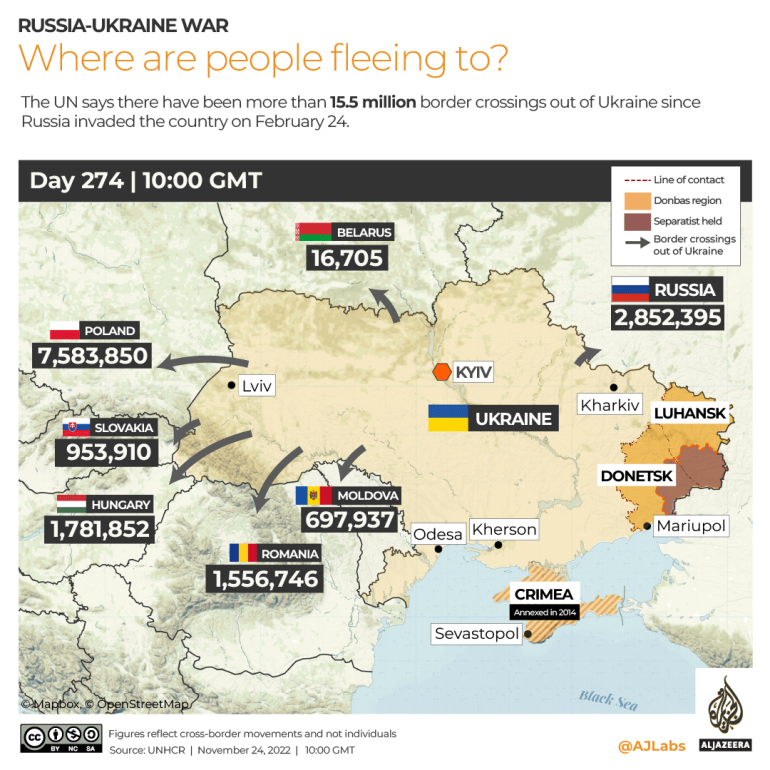

Since Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine began on February 24, 2022, more than 11 million Ukrainians have entered the European Union and the 27-member bloc has been quick to offer refuge through its temporary protection scheme.

Under this directive, Ukrainians are allowed to avail of the bloc’s medical services and accommodation and also work freely in the EU, until 2024.

Bram Frouws, director of the Geneva-based Mixed Migration Centre, told Al Jazeera that as more Ukrainians head towards the EU this winter, the bloc faces new challenges.

“What remains to be seen is how European populations and their governments are going to respond to this. They’ve all been very welcoming and supportive so far, but at the same time, this support could reduce with Europe also facing an energy crisis. But I still think people will be empathetic towards Ukrainian refugees, despite high energy bills,” he said.

But, Anitta Hipper, EU Commission spokeswoman for home affairs, told Al Jazeera that Europe is prepared for any scenario.

“Through the bloc’s solidarity platform, the European Commission is continuously discussing a contingency plan with member states and Schengen associated countries. Under this plan, we’ve already been making a lot of progress to increase reception capacities and ensuring that the reception facilities are well-equipped for winter,” she said.

Administration challenges

Yet, Vera Gruzova, a 34-year-old from Odesa, currently living in Brussels, told Al Jazeera that Ukrainians who are new to the EU have faced administrative problems.

“In some EU countries, the EU’s temporary protection directive requires Ukrainians to have an address while submitting their documents,” said Gruzova, who arrived with her son in Belgium on March 5.

“When the war started, support groups on social media channels were filled with many people agreeing to host Ukrainians, making it easy for many of us to get an address immediately. But in recent months people have been finding it hard to find host families or homes for a short period quickly, making the administration work to avail the temporary protection scheme harder,” she added.

Anastasia Varvarina, a 39-year-old photographer from Odesa, also now in Brussels, said she has seen several social media posts by Ukrainians asking for help to find accommodation to process temporary protection documents.

“When I came to the EU with my best friend and four cats, we were truly overwhelmed with all the kindness and support showered on us. People were quick to host us which is not an easy thing to do for people who have just experienced trauma. We are so thankful for the instant support,” she told Al Jazeera.

Acknowledging this obstacle, Hipper said the European Commission launched “the Safe Homes initiative” in July to assist EU nations and civil society in ensuring Ukrainians fleeing the war are provided with safe housing.

“While we have not yet seen a huge number of people arriving from Ukraine with the onset of winter, we are continuing to coordinate with private and international organisations to ensure everyone who arrives can avail housing facilities and process their temporary protection documents quickly,” she told Al Jazeera.

What else is the EU doing?

So far, 4.8 million refugees from Ukraine have registered for the EU’s temporary protection scheme, according to a November report by the United Nations refugee agency.

As of October 31, Poland, an EU nation which shares a border with Ukraine, has registered the highest number of Ukrainians under the temporary protection directive

The bloc has also rolled out 523 million euros ($543m) in humanitarian aid to Ukraine and pledged to further support countries neighbouring Ukraine such as the Czech Republic, Moldova, Poland and Slovakia.

Frouws explained that the bloc understands that strong support for Ukraine and the countries nearby is likely to mean fewer people travelling further west, to countries such as France or Germany.

“So there’s a bit of self-interest there as well. But overall when it comes to Ukrainian refugees, there is pan-European support,” he added.

Putin triggering the refugee crisis?

On Tuesday, Andriy Yermak, head of the Ukrainian president’s office, said Russia is trying to destabilise Europe.

“Their goal is obvious: to cause a large-scale humanitarian catastrophe, to provoke another refugee crisis in Europe. It’s either force Ukraine to make peace or force the West to force Ukraine to make peace,” he wrote in a tweet.

While the Kremlin has previously denied weaponising migrants, the EU has begun fortifying its borders with Russia and Moscow’s main ally, Belarus.

Countries such as Poland have begun building a barbed wire fence along the border with Russia and Lithuania has built a wall along the frontier with Belarus.

“There’s anxiety in Europe that something like what happened last November with the migration crisis along the bloc’s borders with Belarus, could occur again,” Frouws told Al Jazeera.

“But [fortifying European borders] could also close the door to Russians in urgent need of international protection or other displaced people from other nationalities trying to seek asylum. So it is important to come up with a better and comprehensive approach. Walls aren’t the answer,” he said.

As the EU’s interior ministers convene in Brussels on November 25 to discuss migration issues along all migratory routes including from Ukraine, Hipper reiterated that the bloc stands ready for any challenge.

“Whatever Russia is down to with respect to migration, we will respond by fully supporting Ukrainians and people from other nationalities impacted by Putin’s actions,” she said.