Ukraine wants a special tribunal to prosecute Putin. Can it work?

Ukraine President Zelenskyy calls on the US to support the establishment of a special tribunal for the crime of aggression.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has urged the United States to support the creation of a special tribunal to try the Russian leadership with the crime of aggression for waging war on Ukraine.

“Peace is impossible without justice and justice is impossible without due process of law,” Zelenskyy said in a video message read by Andriy Yermak, his presidential chief of staff, at an event held by the United States Institute of Peace on Wednesday.

Keep reading

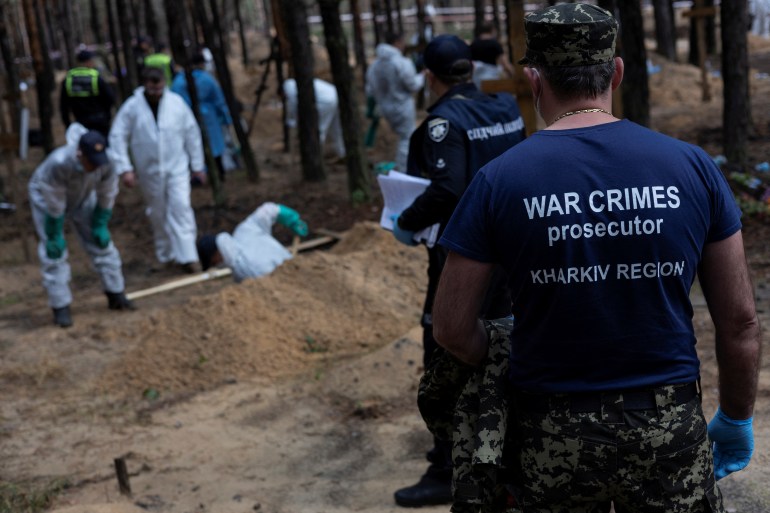

list of 3 itemsUkraine war crimes investigation receives support of 45 nations

Will Russia be prosecuted for war crimes committed in Ukraine?

“This is why it’s indispensable for this peace formula to establish a special tribunal for the crime of aggression committed from Russia against Ukraine,” he added.

The president’s plea came on the back of a months-long effort by Ukrainian representatives to lobby European countries and the US for the formation of a special tribunal – a proposal that has raised doubts over its legality and concerns over the issue of selective justice, some experts say.

Often called the “mother of all crimes”, the crime of aggression is committed when a country’s leadership uses military force against another state illegally – in this case, the accused would be Russian President Vladimir Putin and his inner circle.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) cannot prosecute nationals of a non-party state with the crime of aggression, and Russia is not a member. The international court is instead investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Ukraine, which are hard to link directly to orders from the Kremlin.

‘A means to an end’

The push for a special tribunal gained momentum last week after European Union Commission Chief Ursula von der Leyen backed the proposal. Soon after, France became the first European country to publicly declare its support. Baltic states and the Netherlands are reportedly also on board, while the US, Germany and the United Kingdom have expressed reservations.

Von der Leyen said that the special tribunal could only be formed with the backing of the United Nations. As Russia has a veto at the UN Security Council due to its status as a permanent member, a vote could only have a shot at the UN general assembly. The Kremlin strongly rejected the proposal, saying it would have no legitimacy.

The Commission proposed two options. A standalone international tribunal based on a multilateral treaty or a “hybrid court” integrated into a national justice system with international judges. In both cases, UN blessing “would be essential,” read a Commission paper published on November 30.

The tribunal would target a small number of defendants, including the Russian political leadership and senior military leaders, that would likely have avoided facing justice at the ICC, said Philippe Sands, professor of international law at University College London, who was the first to propose the creation of the special tribunal.

“I foresaw the possibility of ending in a situation in three to four years with a handful of low-grade individuals charged before the ICC – but not those ultimately responsible for the atrocity,” Sands told Al Jazeera. After he fleshed out the idea for a tribunal in an opinion piece in the Financial Times, Sands said he received an unexpected barrage of calls from experts and leaders, including former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

“And now a draft proposal is circulating at the United Nations general assembly,” he said.

While the chances of seeing Putin and other senior Russian officials appear at an international court are currently remote, Sands believes that it could persuade those in Putin’s inner circle to break ranks. “For me, the idea of a special tribunal is a means to an end, not an end in itself,” he said.

‘À la carte’ justice

Opponents of the special tribunal say it would divert funds away from the ICC and undermine its work. The international court Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan pushed back against the idea of a tribunal, saying that while the ICC can’t prosecute Putin, his senior officials could be tried. “We should avoid fragmentation, and instead work on consolidation,” Khan told the annual meeting of the ICC’s oversight body on Monday.

The tribunal would also require a strong effort from the EU to win support among countries from the Global South which could see it as a display of selective justice, said Makane Moïse Mbengue, professor of international law at the University of Geneva.

A UN resolution in mid-November, which called on Russia to pay war reparations to Ukraine, passed with 94 votes in favour, 14 against and 74 abstentions. By contrast, 35 countries abstained from voting on the UN resolution condemning the Russian annexation of four territories of Ukraine.

“Such a strong number of abstentions indicates that countries do not necessarily agree that a special judicial treatment should be given to Ukraine,” Mbengue, who is also president of the African Society of International Law, told Al Jazeera. And the insistence on establishing a tribunal against Moscow met suspicion from those who question why that same move was not applied to address other alleged international crimes, including the US-UK invasion of Iraq.

“There is a feeling that international justice is a bit à la carte,” Mbengue added.

The prospect of a UN resolution passing with a weak majority would send a negative message on how strong the international community’s support for Ukraine is.

For this reason, the decision by the EU to publicly endorse the tribunal was received with a degree of irritation among several UN member states, especially among G7 countries who were concerned that a vote at the general assembly would create “an excessive polarisation between the Global South and the North,” a diplomatic source with knowledge of the matter said. But there are concerns as well over the precedent the tribunal would set. “If you can do it to Russia today, you could do it to me tomorrow,” the source added.

There are also questions over the legal basis of the options outlined by the EU and the actual effect the court would have. It is not clear yet, for example, how the tribunal would address the issue of head-of-state immunity.

Furthermore, “the body would not have the backing of the security council, meaning that there would be no legal requirement from other countries to collaborate,” said Anthony Dworkin, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations on human rights and justice.

As a result, an investigation at the court would be “something hanging over [Putin], but not something he would strongly have to fear,” Dworkin added.