Finland mulls joining NATO after Russia’s war in Ukraine

As the war in Ukraine rages on, another country with a storied history and long border with Russia is growing concerned.

Helsinki, Finland – For decades, Finland refused to take sides for or against Russia, a position that kept the peace but also confined its sovereignty.

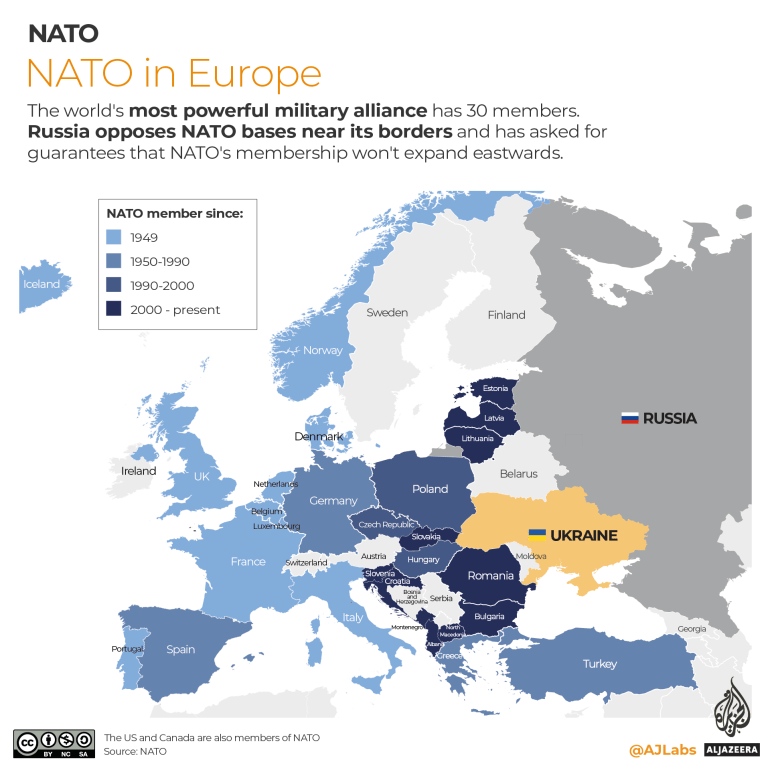

In light of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, its neutrality policy may soon change as the Nordic country that shares a 1,340km (830-mile) border with Russia contemplates joining the NATO military alliance.

Keep reading

list of 2 itemsRussia-Ukraine crisis: Can US sanctions sway Putin’s thinking?

On Thursday, the country’s President Sauli Niinisto said Finland was to review its security policy to decide whether to join NATO.

“When alternatives and risks have been analysed, then it’s time for conclusions,” Niinisto told reporters, referring to the possibility of Finland joining the defence alliance.

“We have safe solutions also for our future. We must review them carefully. Not with delay, but carefully,” he said.

On Wednesday, Finland’s Prime Minister Sanna Marin said discussions on possible NATO membership should take place at several levels with a view to establishing a national consensus.

Meanwhile, a recent poll by public broadcaster Yle found 53 percent of Finns now support joining NATO, a dramatic rise from merely 19 percent five years ago.

And a citizens’ petition on holding a referendum on Finland’s NATO bid gathered the 50,000 signatures needed for parliament to debate it in less than a week.

“Before [the Ukraine crisis], I didn’t want to have to choose between East and West,” Joonas, a 30-year-old brewer from Helsinki, told Al Jazeera. “But now with these actions, I think there’s absolutely no question about it. I guess it’s the time of picking sides.”

Joonas’s words are representative of a shift in public opinion.

“NATO has long been a topic that politicians have not wanted to seriously discuss but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine radically changed this and opened the floor for NATO talks,” Pia Koivunen, an historian at the University of Turku, told Al Jazeera.

Complicated history

The history with Finland goes back to the 19th century when Russia took it from Sweden during a war in 1808.

“Finland has always been a borderland between the East and the West, first part of the Swedish kingdom, then an autonomous grand-duchy of the Russian Empire and finally independent since 1917,” Koivunen said.

“Throughout the history, there has been wars and suffering, but also business and cultural contacts between the countries.”

Under Russian Tsar Alexander II, Finland was allowed a special status within the Russian Empire, with its own currency and largely running its own affairs, although Finnish itself was not recognised as an official language until 1902.

Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Finland was peacefully granted independence by Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, although a bloody civil war soon broke out between the ruling conservative party and the communists.

Then in November 1939, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin attempted an invasion in what became known as the Winter War.

The Winter War

The determined Finns showed fierce resistance: vast stockpiles of then-legal heroin, consumed like aspirin, kept the Finns fighting through their runny noses.

The Soviet Union suffered huge losses, with one sniper alone, Simo Häyhä, nicknamed the White Death, racking up 505 confirmed kills.

“The Winter War is one of the central historical topics that constitute our national identity,” Koivunen said.

“Finns fought a bloody civil war in 1918 and thereafter the society was very divided and polarized between the whites and the reds. The Winter War united the country against a common enemy.”

The Finns managed to hold off the Red Army’s advance and kept their freedom, but lost a huge chunk of territory.

Later during World War II, Finland allied with Nazi Germany to try and take it back, but lost and had to pay reparations to the Soviet Union.

The promise of neutrality

When World War II gave way to the Cold War, Finland found itself in a unique position after its leaders signed a 1948 treaty with Moscow, in which it promised to join neither NATO, nor the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact.

Unlike other countries aligned with one or other of the two main power blocs led from either Washington or the Kremlin, Finland was part of neither, allowing it some flexibility.

But this came at a price. While officially neutral, the Soviet Union exerted pressure on Finland.

“This period, which is called Finlandisation, we were in the Soviet security sphere and had to take into account Russia’s military and foreign policy interests, but at the same time, we developed our own Western type of parliamentary democracy and market economy,” Markku Kangaspuro, a professor of Russian and Eastern European studies at the University of Helsinki, told Al Jazeera.

“It was a superpower neighbour and quite an important trade partner, and this, of course, gave it some leverage over Finnish domestic politics and society. For example, the conservative party was always in opposition and not accepted into government by the other Finnish parties,” Kangaspuro added.

Koivunen said, “Finland had lost the war and, in order to keep her sovereignty, she had to compromise her political independence.

“At the same time, President Urho Kekkonen kept contact with the West and attempted to find room for manoeuvring, wherever it was possible. Finlandisation defined like this was, in the end, a successful method to survive and develop into a Nordic welfare state with a giant, totalitarian neighbour,” she added.

But the Cold War would not last and with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland moved closer to the West, joining the European Union in 1995. But it was still careful not to anger its bigger neighbour.

“We have kept our military non-aligned position, although we cooperate with several of our neighbour states such as Sweden, and the United States, and also NATO,” said Kangaspuro.

“Our relationship has been very practical, pragmatic, and so far, Finland has been a neighbour with whom Russia does not have major problems, compared with almost all of its other neighbours.”

But with the attack on Ukraine, Finnish public opinion has shifted in favour of NATO dramatically. Similarly, Sweden, which has also stayed out of NATO, has plans to significantly raise its defence budget.

Slow, cautious

Could this be the end of Finnish neutrality?

According to Kangaspuro, Finland’s approach remains slow and cautious.

“It’s the shock effect after Russia’s attack on Ukraine – people were scared and this was the first reaction for them,” he said.

“[But] the consensus is that we are not in a hurry. Russia doesn’t pose a military threat to Finland at the moment, and not next week. It is also not time to make these kind of decisions to apply for NATO membership and to make tension between Europe and Russia even more dangerous, to change the power balance in Europe. And that seems to be the position of Sweden as well,” Kangaspuro added.

But even as the Russian government is viewed with suspicion, for ordinary people this does not appear to be the case.

“I spent a month in Russia about seven years ago, coming on a train from China,” Joonas recalled.

“By chance, there was a changeover in the Russian army. They were all coming home at that time and new recruits were coming in. So I talked with a lot of these guys who were maybe 18-19 years old, and they had just spent two or three years out of their home and you’d think they’d be kind of maybe brainwashed or indoctrinated,” he said.

“And when they heard that I’m from Finland, they all expressed their respect. They all were very familiar with our history with Russia, and they all knew about it. And chatting with them gave me the thought that OK, we are not enemies here.”