French presidential election: All you need to know

About 48 million French voters will choose their leader among 12 candidates.

About 48 million eligible French voters will be asked to choose who will govern the nation for the next five years.

Never before in the history of the Fifth Republic – founded by Charles de Gaulle in 1958 – a presidential election has been held in such a dramatic and volatile context.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsZemmour: French Jews slam far-right Jewish presidential hopeful

French far right’s Zemmour backs limited welcome to Ukrainians

After two years of a once-in-a-century pandemic, the climate emergency and now the Ukraine war – the first invasion on European soil since the end of World War II – voters will have to decide whether they give President Emmanuel Macron a second chance or change course in a more radical way.

Here are some of the main things to know:

When are the elections?

Elections in France are held on Sundays. The first round of this year’s presidential elections will be held on April 10. The top two candidates will face each other off in a second round on April 24.

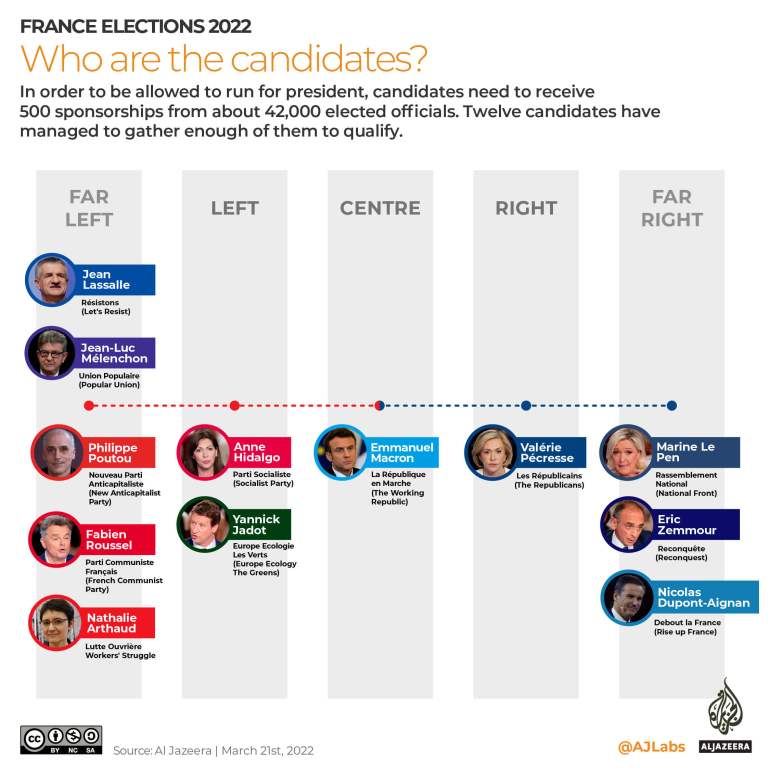

Who are the candidates?

In order to be allowed to run for president, candidates need to receive 500 sponsorships from about 42,000 elected officials.

Sponsorships had to be certified by the Constitutional Council – France’s Supreme Court – by March 4.

Twelve candidates have managed to gather enough of them to qualify:

- Nathalie Arthaud (Lutte Ouvrière – anti-capitalist)

- Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (Debout la France – right)

- Yannick Jadot (Europe Ecologie Les Verts – green)

- Anne Hidalgo (Parti Socialiste – socialist)

- Jean Lassalle (Résistons – independent)

- Marine Le Pen (Rassemblement National – far right)

- Emmanuel Macron (La République en Marche – centrist)

- Jean-Luc Mélenchon (Union Populaire – radical left)

- Valérie Pécresse (Les Républicains – conservative)

- Philippe Poutou (Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste – anti-capitalist)

- Fabien Roussel (Parti Communiste Français – communist)

- Eric Zemmour (Reconquête – far right)

What are the main issues?

Until the invasion of Ukraine by Russia on February 24, there was a general feeling among voters that candidates were not talking about the issues they cared about the most – purchasing power and the high cost of living, healthcare, and the fight against climate change.

Instead, most debates focused on the divisions within the left, the levels of the inheritance tax (less than 25 percent of the French taxpayers owe it) and the names people should be giving to their children.

“The war in Ukraine has put at the centre of the debates what the candidates propose when it comes to vital issues,” said Laure Cometti, a seasoned political journalist.

“They’ve had to talk about how they would cut France’s and the European Union’s reliance on Russian energy and food supplies – which bears the question of how to decarbonize the economy – as well as how to protect the country, potentially via an EU army.”

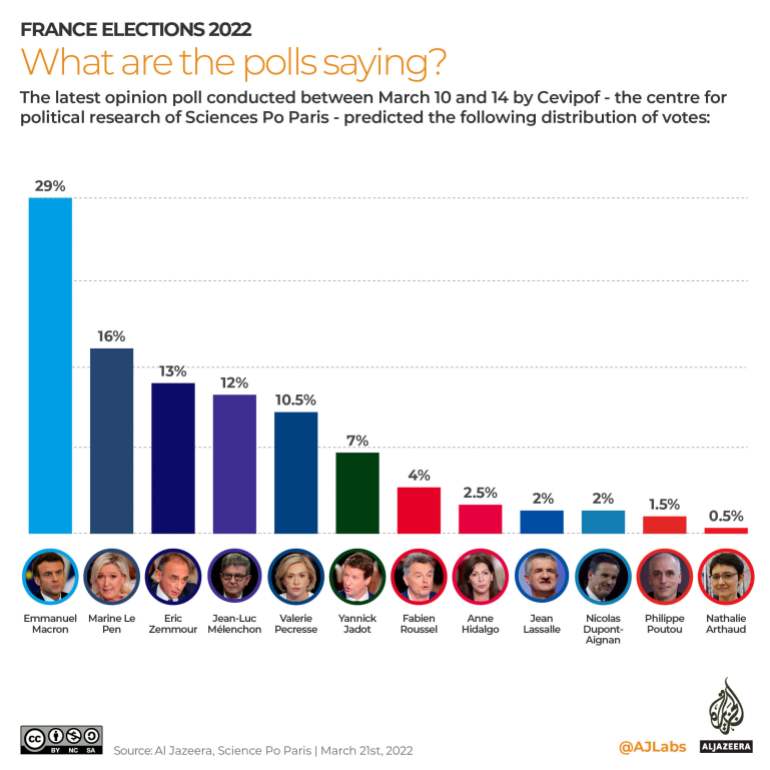

What are the polls saying?

For months now, every single poll has predicted Macron will face far-right Marine Le Pen off in the second round on April 24. The latest salvo says no different.

Cevipof – the centre for political research of Sciences Po Paris – has been conducting the most thorough rolling study of the electorate thanks to a 13,749 strong sample group.

In previous elections, its margins of error have proven to be very small, less than 1 percent, hence its reliability.

The latest opinion poll (PDF), conducted between March 10 and 14, predicted the following distribution of votes:

- Emmanuel Macron – 29 percent

- Marine Le Pen – 16 percent

- Eric Zemmour – 13 percent

- Jean-Luc Mélenchon – 12 percent

- Valérie Pécresse – 10.5 percent

- Yannick Jadot – 7 percent

- Fabien Roussel – 4 percent

- Anne Hidalgo – 2.5 percent

- Jean Lassalle – 2 percent

- Nicolas Dupont-Aignan – 2 percent

- Philippe Poutou – 1.5 percent

- Nathalie Arthaud – 0.5 percent

In the likely event of a second round between Macron and Le Pen, the sitting president would defeat her far-right challenger 59 percent to 41 percent, which is a much thinner margin than in 2017 when he beat her 66 percent to 34 percent.

Macron on the rise

Macron has been leading the polls for years now, with a steady base of 24-25 percent of the electorate planning to vote for him in the first round. An unusually high score for a sitting French president.

“Emmanuel Macron, thanks to his pro-European and progressive message has managed to secure voters from the centre-left who used to vote for the Socialist Party. Economically, he’s implemented pro-business policies to seduce voters from the right,” said Hugo Drochon, professor of political theory at the University of Nottingham.

“Consequently, a new divide has emerged between the centre and the extremes. That’s hurt traditional parties both on the left and on the right,” he said.

Hence the historically low polling of conservative Pécresse and socialist Hidalgo, who struggle to reinvent their parties’ messages in light of climate change, digitalisation and globalisation.

The French president, who has also been presiding the European Council since January, is benefitting politically from the war in Ukraine: the famous “rally-round-the-flag effect”. He now polls at 29 percent, a five-point jump in about a month.

None of the other candidates is deemed qualified enough to do a better job than him, with 61 percent of the voters trusting the 44-year-old leader to make the right decisions when it comes to the Ukraine war.

He is increasingly seen as a protecting figure in uncertain times and his longstanding pro-EU message resonates even louder these days as 32 percent of voters say the war in Ukraine will have an effect on their choice.

“The current context plays in favour of Macron,” said Cometti. “People have credited him for his handling of the pandemic and all the money he poured into the economy to keep it afloat ‘whatever the cost’. He benefits from being already in charge and people know he can manage a crisis.”

Shifting dynamics

Le Pen, the historic far-right figure running for a third time, appears once again to be Macron’s most serious challenger.

Although polls have repeatedly shown over the years that French people do not want to see a rematch of the 2017 elections, it is the menu they will likely be served with.

Her persistent message on purchasing power – the number one concern for voters this year, made even more significant by the consequences of the war in Ukraine – seems to be working, especially among the working class.

She also now benefits from the candidacy of populist Eric Zemmour, after he posed a very serious threat to her last year when polls had him ahead of her last November.

But Zemmour’s rage against Muslims, women and immigrants has made her look like a more reasonable candidate, even though they share similar views and ideas.

And the former journalist’s long-established admiration for Russia’s Vladimir Putin has also cost him lately.

“Dramatic events like wars weaken candidacies that have small political capitals. Zemmour is a newcomer in politics and he’s made a terrible mistake by saying he would not take in Ukrainian refugees. That made him look heartless,” said Bruno Cautrès, a political researcher at Sciences Po Paris.

The last hope of the left

Seen by many as the last hope of the left-wing camp, Jean-Luc Mélenchon defines himself as an “electoral turtle”.

Currently polling about 12 percent, he has seen a rise in the polls lately and hopes to pull the same move as in 2017, when he went from 14 percent to 19 percent in the last few weeks of the campaign.

But this time around, he is facing multiple left-wing candidacies that will likely prevent him from qualifying for the second round.

Hence the message he has been hammering: “I am the efficient vote on the Left.”

On March 20, he gathered tens of thousands of his supporters in Paris’s Bastille Square for a “march for the 6th Republic”, one of his key proposals to change the political system.

It was the biggest rally of the campaign so far. But will it be enough to convince enough green, socialist and communist voters?

“Voting intentions have almost crystallised. However, the threshold to qualify for the second round is unusually low this year, around 16 percent. That means candidates like Zemmour, Mélenchon or Pécresse still have a chance,” said Bruno Cautrès, who conducted the Cevipof study.

“But only one of them has momentum in the final phase of the campaign, and it’s Jean-Luc Mélenchon,” he said.

One element could disrupt predictions though: abstention. It appears it will be stronger this year than in all previous elections.

“There’s a widely shared sentiment of horror with what is happening in Ukraine. After the Yellow Vest crisis in 2018-2019, two years of pandemic, the climate emergency and now a war in Europe, people are tired and feel like it all fades into one big endless crisis. This could explain why abstention will likely be higher this time around … and potentially make room for a surprise,” said Cautrès.